[simple-author-box]

INTRODUCTION:

Kapi or Karnataka Kapi is an old raga. Sahaji’s Raga Lakshanamu, Tulaja’s Saramrutha,the Anubandha to the Caturdandi Prakashika and the Sangraha Cudamani have documented this raga. We have compositions in it from the pre-trinity times which are available to us through the Sangeeta Sampradaya Pradarshini (SSP). We have grounds to believe that Trinitarians have composed in this raga perhaps with different musical flavors. The northern raga Kafi is spoken of, more as an equivalent of Karaharapriya while Kapi is truly different and in terms of the Hindustani music scheme, it belongs to the Kanhra/Kanada family of ragas.

Kapi is a raga which has become extinct in its original form but survives today in a much metamorphosed version or versions. Apart from its evolutionary history, one additional aspect of this raga merits attention. It probably spawned or was at the epicenter of a family of ragas which shared a common melodic motif G2M1R2S. Each of the ragas in this family went on to transform itself in an evolutionary process and are today in our midst, each with their own distinct melodic identity and remarkably distinguishable from one another.

In this blog post , we would take a deep dive into this raga and also cover the aspects highlighted above. In a later blog post we will cover the comparison of this raga with a few other ragas with which it shares common melodic material.

KAPI – ITS CURRENT FORM:

Before we look at the history of Kapi, it would be appropriate to take stock of the current form of this raga.

Kapi (rather modern Kapi) is grouped as a bhashanga janya under the Kharaharapriya mela/Sriraga raganga with anatara gandhara, suddha dhaivatha and kakali nishada as anya svaras, depending on the version of the composition. There is no strict arohana or avarohana for the raga today².This modern day Kapi is encountered in renderings of Tyagaraja’s kritis such as “Meevalla Gunadosha”, Papanasam Sivan’s “Enna Tavam seidhanai”, the javali ‘Parulannamata’ and the tune melody of “Jagadodharana” of Purandaradasa.

With this brief introduction let us look at the antiquity of this raga and the transformation it had undergone to reach its present stage.

Sahaji’s Ragalakshanamu (Circa 1700):

Kapi is not encountered in older texts including that of Govinda Dikshitar and Venkatamakhi. The first person to record this raga in the post 1700 period was King Sahaji who had captured the ragas in currency during his lifetime in this work “Ragalakshanamu’. According to him, the raga is sampurna, desya and is under the Sriraga mela and in the avarohana sancaras sometimes madhyama and dhaivatha are eliminated.⁴

As regards the usage of the terminology ‘sampurna’, it is to be noted that in all old musicological texts a raga is treated as sampurna if the seven svaras occurred in the arohana and avarohana taken together.

Tulaja’s Saramrutha (circa 1736 AD) ⁶:

Next is the text “Saramrutha” which records the raga. According to Tulaja, this raga is under the Sriraga mela , sampurna with sadja as graham, amsa and nyasa with the svaragati of the raga being niraghata or unlimited. The murccanas that Tulaja gives for alapa and gita indicate a sequential progression of svaras, much like modern day Kharaharapriya! Also according to Tulaja this raga is auspicious and is to be rendered in the evenings.⁶

Raga Lakshana anubandha of Muddu Venkatamakhin³:

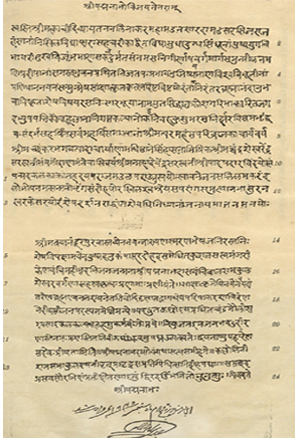

Venkatamakhin in his CDP does not deal with Kapi or any other raga which shares a similar melodic structure or with a different name. The Anubandha to the CDP which is most probably a work of his great grandson Muddu Venkatamakhin or his son Venkata Vaidyanatha Dikshitar who was the preceptor of Ramasvami Dikshitar, provides reference with a lakshana shloka for Kapi under mela 22 (Sriraga) as under:

Kapi ragascha sampurnah sagrahah sarvakalika

The shloka does not denote any anya svaras occurring or whether any svaras are vakra or varja in the arohana or avarohana.

Summary of the above:

The raga Kapi as documented by the three authors as above has one common theme. It was more or less modern Kharaharapriya in terms of its scalar structure. Additionally according to Sahaji, the dhaivatha and madhayama were sometimes skipped in the avarohana. Based on this observation one can postulate that Kapi probably featured prayogas like sNPMGRS or sNDNPMGRS (which are found in Karnataka Kapi of today) and madhyama varja prayogas such as NPG…R (which also do occur in Karnataka Kapi). With that we move on the Subbarama Dikshitar and his work the Sangita Sampradaya Pradarshini to take stock of what Kapi was.

KAPI OF THE SSP ¹:

Subbarama Dikshitar provides us with three sets of inputs in the Sampradaya Pradarsini:

- Muddu Venkatamakhin’s raga lakshana shloka and his lakshana gitam

- His own commentary on the raga lakshana and his sancari

- Compositions of Muthusvami Dikshitar and that of three pre-trinity composers namely Margadarshi Sesha Iyengar, Srinivasayya and Bhadracala Ramadas

The Muddu Venkatamakhi gitam too offers us no further light in terms of raga lakshana. It is Subbarama Dikshitar’s commentary that provides us with some practical insight as to the Kapi of yore.

SUBBARAMA DIKSHITAR’S COMMENTARY:

According to Subbarama Dikshitar, the arohana and avarohana murccanas of Kapi under mela 22 ( Sriraga) are SRGMPDNs/NDPMGGRS. Attention is invited to the usage of the nishada without touching the tara sadja and the janta gandhara and the dirgha rishabha. Further according to him the gandhara and rishabha are the jiva & nyasa svaras. Subbarama Dikshitar also gives us a few choice phrases which he says are native to the raga:

NSGMGmRS , NNSDPMGmRS, RGMPDNPMGMRS, SNPMGMRS, PMGGMRS, NPMPDRS, NSDNSRGMRS etc

Subbarama Dikshitar also observes that kakali nishada (N3) and antara gandhara (G3) occur in the phrases sNPMP DsNPMP, PMGMR and MPGMRS, though the same is not found notated in the compositions that he gives subsequently including his own sancari. So his observation is really a conundrum as we do not have a record of the said compositions or renderings incorporating the said prayogas.

For us the Kapi that Subbarama Dikshitar paints has one major feature which is the occurance of the anga/leitmotif “GMR” which is the hallmark of modern day Kanada. The melodic tinge of GMRS is so pronounced for example in the notation of the kriti “Rangapate Pahi” of Sesha Iyyengar that it sounds more as modern day Kanada for us and it should be remembered that the composition dates back to the pre-trinity era which did not have a raga called Kanada. In that sense, Karnataka Kapi can surely be called the precursor of modern Kanada.

ANGAS – A NOTE ON MUSICAL LEITMOTIFS

The murcchana or leitmotif ‘GMRS’ which occurs in profusion as a melodic signature is not just a property of Karnataka Kapi but also a host of other ragas and the notation in SSP is evidence of it. Beyond the raaganga-janya or Melakarta-janya relationship, in olden times in our music, ragas had a common melodic bond through a shared murrcana or anga. Even ancient texts like Anupa Sangeeta Ratnakara of Bhavabhatta give ragas which have been grouped / classified on such a premise. For example the Kanhra group consists of 14 ragas such as Suddha Karnat, Nayaki,Bageshri, Adana, Shahana, Mudrik, Gara, Huseini, Kafi Kanhra etc. The architect of modern Hindustani paddhati, Pandit Bhatkande, formalized the anga based classification of ragas and he codified a few types of angas in the process¹°:

- Kafi ang – RRGGMMP is the motif and the ragas sharing it include Sindhura & Pilu

- Kanhara ang – GMRS, NDNP and NPGM are the key motifs and ragas sharing it include Shahana, Adana, Durbari etc

- Malhar ang – MRPm MPDs and DPM are the motifs with the ragas being Shuddha Malhar, Mian ki Malhar, Gaud Malhar etc

- Sarang ang – NSR, MR, PR are the motifs and the ragas being Gaud Sarang, Madhmadh Sarang and Vrindavani sarang

Some of the other types include Dhanashree ang, Shree ang, Lalit ang and Gaud ang. Attention is invited to the motifs of the Kanhara/Kanada ang namely GMRS, MNDNP and NPGM which are seen in Kapi. Additionally the janta gandharas of the Kafi anga too merit attention in the context of our Kapi as it is seen as well.

Based on the raga lakshanas and notations that Subbarama Dikshitar gives in the SSP, one can see that this GMRS motif is shared by a host of ragas under the Sriraga mela namely Kapi, Durbar, Nayaki and Sahana. The raga Andhali though grouped under the Kedaragaula mela, shares a similar feature with the gandhara having morphed. The modern day Kanada and Phalamanjari ragas (though not featured in the SSP) sport the GMRS motif as well.

The anga as a musical aspect or a raga attribute has lost its relevance in modern Carnatic musicology. Emphasis on individual notes rather than murcchanas, sequential progression and alignment of the raga’s contour to its melakartha etc have taken roots at the expense of aesthetics and harmonics which were the only yardstick, one upon a time. The anga aspect though a deprecated concept at this point in time, is a useful tool for us to assess the musical contours of Kapi and also to understand the evolutionary path it went through with its sibling ragas such Kanada, Sahana, Durbar etc.

One other music text (older than the SSP) that features the raga Kapi is the Sangeetha Sarvatha Sara Sangrahamu of Vina Ramanujayya published in the years 1859 and 1885 . There is a ragamala gitam given in the work( 1885) starting with the words ‘Karnata konkana’ which is set to 36 ragas each having a line of sahitya in one tala avartha of 10 beats (misra jhampa or catushra matya). Here the Kapi raga portion ( svara and sahitya ) is as under:

P D N P M G , G , R

Ka………………………….pi

Two unique motifs are featured here namely the usage of PDNPM and janta gandhara which would give a Durbar effect to the Kapi.

SUMMARY of SSP’S RAGA LAKSHANA :

The melodic features of raga Kapi as featured in the SSP notation can be summarized as:

- The sequential descent such as sNDP is rare and instead sNPM can be used. So avarohana phrases can be sNPMGMRS, NPGMRS, NDNPMGRS or NDPGMRS

- Again PDNs is also rare and is dispensed with in favor of aroha phrases such as PDNPNs or PNDNs.

- Thus a straight SRGM and PDNs can be avoided and GMRS used in profusion along with DNP (as in PDNP or MPDNP or MNDNP) to establish a unique melodic identity much in line with the northern Kanhra/Kanada ang

- The dhirga gandhara, the janta gandhara or gandhara shaken with kampita gamaka and the nishada which is intoned uniquely as in NPG are hallmarks of this Kapi which again are the key components of the Kanhra/Kanada anga.

For Subbarama Dikshitar, the raga name is only Kapi. Given the evolution that it underwent and to identify its old form, the term Karnataka Kapi was probably coined during the early/mid 20th century to commonly denote all upanga versions.

The above summary provides us with some practical insights about this raga and also gives us clues as to why this form of Kapi has virtually become extinct. Before we look at that, let us look at what some experts/authorities had to say on the raga lakshana of Kapi.

THE COMMENTARY ON KAPI BY MUSICOLOGISTS/AUTHORITIES:

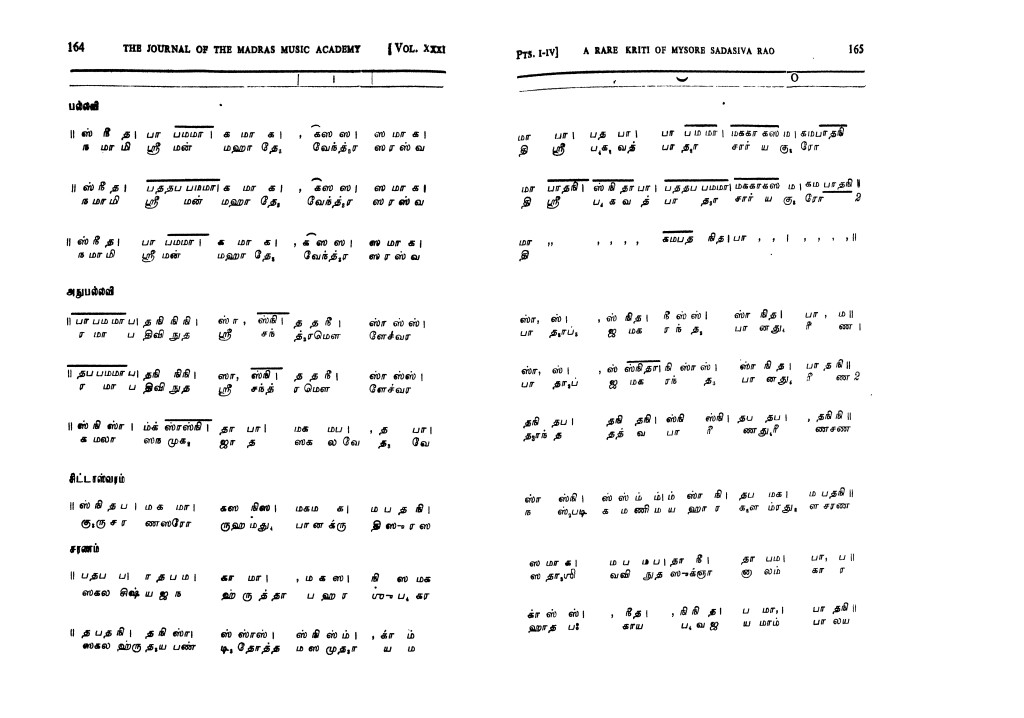

Four documented authorities pertaining to raga Kapi’s lakshana, one of Prof Sambamoorthi, on of Dr T S Ramakrishnan and two instances from the proceedings of the Music Academy discussions are available to us.

THE ACCOUNT OF PROF SAMBAMOORTHI⁷:

According to him, in the lakshya of Karnatic music, we have three varieties of Kapi.

- First is the pure/old Kapi or Karnataka Kapi, immortalized by Kshetrayya in his padas, by Tyagaraja in his piece ‘Cuta murare (Nowka Caritram) and other songs and by Syama Sastri in ‘Akhilandesvari’. This Kapi, in modern day parlance is upanga, meaning it inherits only the svaras of its parent mela Kharaharapriya/Sriraga.

- Apart from this upanga Kapi, there is another upanga Kapi which is evidenced by the tillana ‘udharana dhim’, which is a composition of Pallavi Sesha Iyer (1842-1909). This type of Kapi has srmpns-sndnpmgrs as its arohana/avarohana with Mmp as a visesha prayoga. The kriti ‘Manamohana syamala rama’ is another example of this upanga Kapi. These two type of Kapi’s do not take anya svaras namely antara gandhara, kakali nishada or suddha dhaivatha.

- The third/last type is the bhashanga type made familiar to us by javalis like ‘Vaddani ne’. This bhashanga Kapi is also known today as Hindustani Kapi, Desya Kapi or Misra Kapi. Prof Sambamoorthi further adds that the current tunes (incorporating these anya svaras) of the compositions “Meevalla gunadosha” and ‘Intasoukya” are 20th century innovations.

Prof Sambamoorthi’s observations are exceedingly in line with the forms of Kapi that one encounters in practice. But he seems to have overlooked the version as documented in the SSP including the kriti of Muthusvami Dikshitar.

THE ACCOUNT OF DR T S RAMAKRISHNAN

Dr T S Ramakrishnan, a past member of the Experts Commitee of the Music Academy and acknowledged authority of the Venkatamakhi sampradaya and the SSP, in a lecture demonstration in the Music Academy had this to say when he discussed the position of Sriraga as the 22nd Mela in the Asampurna mela scheme.

The raga Kapi, a rakti raga, would have been perhaps more apt as the ragaanga raga for this 22nd mela, but it had the bashanga tinge and hence could not represent the mela. Even before Venkatamakhin’s days, this raga Kapi , being really the same as our present day popular and major raga Kharaharapriya, had migrated to the North, where it was considered as a ‘thaat’, in their system of music. Later it came back to us with its Northern hue as our modern day Kapi ( with an intermediate stage as our Rudrapriya- It may be noted that Rudrapriya is Harapriya) with pronounced bhashanga features. Venkatamakhin has a lakshya gita for this raga Kapi , which when rendered , sounds entirely like our present day mela raga Kharaharapriya, with no difference whatsoever in its raga picture. Venkatamakhin considered this Kapi as a bhashanga janya under the 22nd mela and has given its name accordingly in the bhashanga khanda of the lakshana gita for the ragaanga raga Sriraga.

THE ACCOUNT OF THE EXPERTS COMMITTEE OF THE MUSIC ACADEMY:

The Experts Committee of the Music Academy does not seem to have discussed individually the lakshana of this raga and its evolution in detail. We have two instances however where in relation to proceedings of related ragas or presentation of rare kritis, the ragas has been discussed.

First is the one when during the 1967 Music Academy session on 24th December of that year, Vidvan Salem D Chellam Iyengar presented 3 rare kritis of Tyagaraja as learnt by his father, the late Salem Doraisvami Iyengar from the legendary Pooci Srinivasa Iyengar. Vidvan Chellam Iyengar presented ‘Anyayamu Seyakura’ in Karnataka Kapi devoid of anya svara kakali nishada. Justice T L Venkatarama Iyer referred to the controversial nature of the raga of this composition and his own patham according to the Umayalpuram school which featured kakali nishada.

One can take note of the fact that the compositions of Tyagaraja in the raga Karnataka Kapi are today either rendered in Durbar or in the modern form of Kapi with anya svaras. The commentary of Subbarama Dikshitar and the assertion of Prof Sambamoorthi also substantiate this point.

EXPERTS COMMITTEE DISCUSSION ON THE RAGA KAPI⁵:

During the Expert Committee Meeting held during the Music Academy Session in the year 2008, the raga lakshanas of a set of allied ragas including that of Kapi had been discussed and the same has been collated & presented by Expert Committee member Dr N Ramanathan. The raga lakshana of four allied ragas Rudrapriya, Karnataka Kapi, Darbar and Kanada were discussed by the Experts panel consisting of Vidvan Chinglepet Ranganathan, Vidushi Suguna Purushothaman, Dr Ritha Rajan, Dr R S Jayalakshmi apart from Dr N Ramanathan. The Academy’s Expert Committee had in the past discussed the raga lakshana of all the other ragas in this set namely Rudrapriya, Durbar and Kanada and had also prescribed the arohana/avarohana of these ragas, but not of Kapi.

The following facts are available to us from the discussions as documented in the Academy’s Journal of the year 2009.

- According to Dr Ramanathan, K V Srinivasa Iyengar has documented Kapi with the use of kakali nishada but use of antara gandhara has not been mentioned by him. According to him the song ‘Anyayamu seyakura’ is in this form of Kapi and he also observes that some render this composition in Durbar.

- According to the Umayalpuram sishya parampara of Tyagaraja, the compositions ‘Anyayamu seyakura’, “edi ni bahubala’ and ‘cutamu rare’ have shades of both Kanada and Durbar without any resemblance of Hindustani Kapi.

- According to Dr Ritha Rajan, the Tyagaraja composition ‘Nitya rupa’ was rendered by Vidvan Ramnad Krishnan in Durbar. Additionally Rangaramanuja Iyengar has documented two versions of the composition, one in raga Kapi and the other in Durbar. Further the compositions ‘Naradagurusvami’ and ‘Edi ni bahubala’ exists both in Kapi and Durbar.

- The Nauka caritra composition “cutamu rare” when sung as notated, has shades of Durbar.

- In general, the Dikshitar school version of Kapi had shades of Kanada with the usage of the phrase ‘sNPMGMRS’, while the compositions of Tyagaraja has shades of Durbar with usage of phrases such as ‘sNsD,PMP,G,MRS’

- From a raga chaya perspective, the raga Rudrapriya is closer to Hindustani Kapi than Karnataka Kapi.

While Prof Sambamoorthi’s account ignored the Dikshitar treatment of the raga, the Academy Experts Committee in its deliberations do not seem to have considered the version of Kapi as envisaged in the Svati Tirunal composition ‘Sumasayaka’ and in the compositions of the Tanjore Quartet.

SUMMARY OF THE EVIDENCE THIS FAR:

Using these data sets to crystallize our understanding, one can divine at least four forms of Kapi, rather than the three forms that Prof Sambamoorthi documents in his account. The four such flavors of Kapi are:

1: This old version or Karnataka Kapi as it is now called profusely uses GMRS along with kampita gamaka ornamented gandhara.The Dikshitar manipravala classic “Venkatachalapate” found documented in the SSP is an example of this flavor. This form is more aligned to modern day Kanada which as a scale goes as SRGMDNs or SRPGMDNs/sNPMGMRS. This flavor of Kapi is completely extinct and the sole surviving example to us is the Dikshitar composition. Any other older kritis in this form of Kapi has been normalized to Kanada. In the context of this statement we need to evaluate the raga lakshana as found in the kritis attributed to Muthusvami Dikshitar, not found in the SSP but published subsequently by Vidvan Sundaram Iyer. See foot note 2.

One other kriti with this flavor which survives today may probably be Svati Tirunal’s composition ‘Sambho Satatam’. As we will see later the melodic fabric of this kriti is different from that of his other composition, the cauka varna ‘Sumasayaka’. The notation of ‘Sambo Satatam’ reveals a profusion of GMRS and a near sequential svara progression. It may be noted that we have Svati Tirunal’s compositions in 3 flavors of Kapi.

2: This flavor of Kapi has lot of janta gandhara with GGRS as leitmotif and features a near sequential svara progression. Flavor 2 Kapi shares nearly the same melodic structure as that of modern day Durbar. In fact, many modern musicologists believe that many of Tyagaraja’s Kapi compositions were normalized to be rendered in Durbar. An example is the composition ‘Nityarupa’. One can also surmise that the GMRS prayoga of flavor 1 Kapi morphed as GGRS to produce this flavor. The GMRS connection between Durbar and Kapi is also seen in the notation of the Dikshitar’s Durbar composition “Tyagarajad anyam najaneham” as found in the SSP. A version of the Syama Sastri composition ‘Akhilandesvari durusuga’ is rendered in this flavor . Tyagaraja’s Nauka Caritra composition is an other example of this flavor.

There is also a hybrid of flavor 1 and 2 as well, having both the GMRS and the GGRS giving both the Kanada and the Durbar effect. Versions of the Tyagaraja kriti ‘Anyayamu Seyakura’ is an example.

3: This flavor of Kapi is bereft of the prayogas GGRS or GMRS. Instead, it has a profusion of gandhara with an elongated kampita gamaka and characterized by the arohana/avarohana of SRMPNs/sNDNPMGRS. This Kapi is not much in currency and is rarely encountered in concert circuits. The pada varna “Sumasayaka”, the Quartet kriti ‘Sri Mahadevuni” and the Chinnayya tillana in this raga are excellent examples of this type of Kapi. The Music Academy Experts Committee Discussion of the year 2008, presented above had discussed flavor 1 and 2 in detail but not this flavor. This is the type of upanga Kapi that Prof Sambamoorthi has referred to in his commentary given above, with the Pallavi Sesha Iyer tillana as an example. It is indeed our loss that we hardly look upon the compositions of the Quartet as authority for raga lakshana. The Kapi in this flavor is found in the following Quartet compositions:

-

Kriti ‘Sri Mahadevuni’ – On Goddesses Brihannayaki of Tanjore

-

Javali ‘Elara Naapai’

-

Tillana ‘Dheem nadru dheem’ on King Camaraja Wodeyar of Mysore

-

Cauka varna ‘Sarasala ninnu’ on Lord Brihadeesvara ( the varna is almost similar to the Svati Tirunal pada varna ‘Sumasayaka’)

4: The Kapi which sports additionally the anya svaras namely antara gandhara and/or kakali nishada with or without suddha dhaivatha, which is the modern day Kapi. Examples are the javali Parulannamata and the the Purandara dasa composition Jagadhodharana.

Curiously we have compositions of Svati Tirunal notated⁸ in 3 of the above flavors and rendered so as well. They are:

Flavor 1 : The kriti ‘Sambo Satatam’

Flavor 3 : The pada varna ‘Sumasayaka’

Flavor 4 : The kriti ‘Vihara Manasa rame’

Though one cannot say with certainty if they were indeed composed so, but the fact we have compositions so rendered is relevant to further our understanding of this raga and the flavors in which it existed. Vihara Manasa sports N3, G3 and D1 as well with N3 occurring in the prayogas such as sN3s while G3 occurs in prayogas like MG3M, MG3S and suddha dhaivatha is found in prayogas like PMD1P⁸.

Subbarama Dikshitar’s commentary in the SSP as to usage of kakali nishada and antara gandhara merits a mention here. According to him sN3PMP and DsN3PMP features kakali nishada while PMG3MR and MPG3MRS feature antara gandhara. Its at variance with what one sees in modern usage. Usage of sN3P or MPG3MRS would cast a different melodic color to Kapi¹.

Amongst the four flavors above, only flavor 4 is the bashanga form and the one which is the most popular today. Flavor 2 does not exist today in practice as it has lost itself to the melodic structure of Durbar in essence. Again save for the Dikshitar composition ‘Venkatachalapate’, flavor 1 type compositions do not exist for they are grouped off under Kanada. From a naming convention perspective, flavors 1, 2 & 3 are called as Karnataka Kapi and flavor 4 alone is either referred to as Kapi or more specifically as Hindustani Kapi.

The cause of Karnataka Kapi’s demise in its old form, the melodic overlap it has with allied ragas or rather its siblings and the evolution of this group of ragas can all be seen in the above categorization ( see Foot Note 1). We next move over to review renderings of the different flavors of Kapi.

DISCOGRAPHY:

Kapi – Flavor 1 or Karnataka Kapi:

On the authority of Subbarama Dikshitar, one can state that this flavor should have been/was the Kapi of yore, the Kapi handled by Sesha Iyyengar, Virabadrayya and others. We do not have authentic oral patantharam of these pre-trinity compositions save for those who might have learnt it from the SSP notation. We can with the evidence of Dikshitar’s composition take it for granted that this version of Kapi was the oldest of the lot and was conforming to the then sampradaya. Presented first is the the kriti as rendered by Vidushi Kalpakam Svaminathan who learnt it first hand from Justice T L Venkatarama Iyer.

Clip 1: Smt Kalpagam Svaminathan renders Dikshitar’s Venkatacalapate

The version presented by the veteran faithfully follows the notation in the SSP. The profusion of GMRS and the kampita gamaka on the gandhara in this old version of Kapi needs to be highlighted here. Also this composition stands out in several counts.

- This is probably Dikshitar’s only kriti with its sahitya being an admixture of Sanskrit, Telugu and Tamil as documented in the SSP. We have two other kritis (one in Sriraga and the other again in Karnataka Kapi ) ‘Sri abhayambha’ brought out by Vidvan Sundaram Iyer and ‘Sri Maharajni’ brought out from the Tanjore Quartet manuscripts, being attributed to Muthusvami Dikshitar.

- The raga name has been adroitly woven into the sahitya of the madhayama kala portion of the kriti as “dIna rakshakA pItAmbaraDhara deva deva guruguhan mAmanAna”, along with his own mudra.

- This composition is on the Lord Venkatachalapathi at the kshetra of Pulivalam, a few miles from Tiruvarur.

The kriti ‘Rangapate Pahi’ as notated in the SSP has been rendered after being normalized to Kanada and as well as to Durbar. The clipping below is an excerpt, being a Kanada version:

Clip 2: Vidushi Prema Rangarajan renders Rangapate

As pointed out earlier Svati Tirunal’s composition ‘Sambho Satatam’ is documented with a profusion of GMRS prayoga⁸. Let’s look at a rendering of this composition. Sangita Kalanidhi Semmangudi Srinivasa Iyer in this Navaratri Mantapam Concert from the 1970’s renders this composition

Clip 3: Semmangudi Srinivasa Iyer renders ‘Sambho satatam’

One can notice that the GMRS is intoned with a muted madhyama in the prayoga and does not give the complete kAnadA effect that one will get with a strong intonation of the madhyama. Listeners may well compare this with the strong madhyama intonation in the GMRS prayoga of the Dikshitar composition particularly the sahitya line in the carana ‘seegramai vandhu’ which combines a kampita gamaka on the gandhara as well. Apart from the GMRS, another motif which is found in both the compositions is the phrase RP as in RPMP.

In this Music Academy concert of 1970, Sri Srinivasa Iyer renders this composition between 1:36: 40 and 1:41:06 I invite attention he makes at the fag end of his rendition at 1:41:07 – “This raga is called Karnataka Kapi and it is neither Durbar nor Kanada” in Tamil.

Here is another edition of the veteran, presenting the same composition, this time at the hallowed precincts of the Temple of Lord Padmanabha at Trivandrum from one of his innumerable Navaratri Mantapam Concerts

The entire concert can be heard here:

http://www.sangeethamshare.org/gvr/SSI_Concerts/SSI_Navarathri/

( Requires Google or Yahoo ID)

Kapi Flavor 2:

The Syama Sastri kriti ‘Akhilandesvari durusuga’ is rendered in both flavor 2 and flavor 4. The hybrid flavor having both Kanada and Durbar in Kapi is best exemplified by Vidvan Ramnad Krishnan’s presentation of the Tyagaraja kriti ‘Anyayamu Seyakura’. In this clipping below, the raga outline that he provides us ahead of the kriti conveys the melodic contours of the kriti to follow with the shades of both Kanada and Durbar.

Clip 4: Vidvan Ramnad Krishnan renders Anyayamu Seyakura

The contrast is provided by Vidvan Nedunuri Krishnamurthi, whose presentation of the same kriti is in modern Kapi.

Clip 5: Sangita Kalanidhi Nedunuri Krishnamurthi renders Anyayamu-seyakura-Kapi

As evidence of the morphing of flavor 2 Kapi to Durbar, the kriti ‘Nitya roopa’ of Tyagaraja is presented next, rendered by Smt Mythili Nagesvaran a votary of the Dhanammal school ( Jayammal ).

Clip 6 : Vidushi Mythili Nagesvaran renders Nityaroopa-Durbar

The presentation is very neatly done in modern Durbar, bereft of any trace whatsoever of Kapi.

Kapi Flavor 3:

The pada varna of Svati Tirunal’s ‘Sumasayaka’ is one of the best versions of this type of Kapi, characterized by SRMPNs/sNDNPMGRS and a dirgha gandhara. We do have some oral versions of this composition where tints of modern Kapi (flavor 4) are thrown in. There is also an equivalent composition that is with the same melodic setting but with telugu lyrics which is a creation of the Quartet being ‘sArasAlanu’. This pada varna starting with the sahitya ‘Sarasalanu’ has a few differences with ‘Sumasayaka’:

- The varna has sahitya for the muktayi svaras and for the ettugada svaras barring the last one , which like Sumasayaka is in a raga malika format. Sumasayaka does not have sahitya for the muktayi svaras and ettugada svaras.

- In terms of ordering of the carana ettugada svaras there seems to be a small change. The 2nd & 3rd ettugada sequences of ‘sumasayaka’ are reversed in ‘Sarasalanu’.

- While ‘Sumasayaka’ has Kalyani, Khamas, Vasanta and Mohanam as the ragamalika svaras for the last ettugada, the Quartet creation has Hamirkalyani, Chakravakam, Vasantha and Mohanam instead.

- The varna mettu of the varna is exactly the same as that ‘Sumasayaka’.

- While the ankita for Sumasayaka is ‘sarasijanabha’ in ‘Sarasala ninnu’ it is ‘brihadeesvara’

The essence of this type of Kapi is best encapsulated by the muktayi svara of Sumasayaka/Sarasalanu, which begins with the well oscillated gandhara.

Clip 6: Vocalists C Saroja & C Lalitha render the Sumasayaka-Muktayi svara

Presented below is the complete pada varna ‘sumasayaka’ by the scion of the Dhanammal family, Sangita Kalanidhi T Brinda.

Clip 7: Smt T Brinda renders Sumasayaka-Karnatakakapi

Attention is invited to the oscillated gandhara which is the hallmark of this version and punctuated with prayogas such as PNDN, GRnS, PNsr and sNDNP. Attention is also invited to the intonation of the nishada as in the carana refrain where it appears as a svarakshara, “mAnInI hAtE hrt tApam”. As one can observe that the nishada is different from the one we find in Sriraga for example, to which clan, Kapi belongs to.

We next move over to the two other compositions of the Quartet namely the kriti ‘Sri Mahadevuni” composed on Goddess Brihannayaki of Tanjore and the tillana ‘Dheem Nadru dhim dhim” composed on King Chamarajendra of Mysore by Cinnayya of the Tanjore Quartet. Though we do not have renderings of these two compositions, the notations from the manuscripts have been published in the “Tanjai Peruvudaiyan Perisai”⁹. The notations clearly bear out the fact that the Kapi is of flavor 3 with an operative arohana/avarohana SRMPNs/sNPMGRS with dhaivatha being vakra as in PNDNP, MNDNP and sNDNP. Gandhara is obviously kampita and is encountered in its dirgha variety. GMRS is not to be seen in this version. Sangita Kalanidhi Ponnayya Pillai while publishing the compositions has added the footnote that the composition has been structured skillfully avoiding the use of anya svara⁹.

In so far as flavor 4 of Kapi is concerned, the kritis pointed out elsewhere in this post features this form such as “Meevalla Guna dosha” or “Enna Tavam saidhanai” of Papanasam Sivan.

ALLIED RAGAS OF KAPI:

The ragas Sahana, Durbar, Nayaki and Kanada along with Phalamanjari share a close melodic relationship to Karnataka Kapi. But from the standpoint of modern Kapi, the ragas Saindhavi and perhaps Salaga Bhairavi share a close affinity. In a followup post we will look at the comparison of these ragas.

CONCLUSION:

The raga Kapi and its evolution is an interesting study. The modern Kapi is most probably the final product of this long cycle of evolution. There does not seem to be any other raga with such different shades and implementations spanning centuries in our musical firmament. Interestingly in Hindustani Music, this raga/scale was considered the scale of suddha svaras and hence was given a pride of place and Rajan Parikkar’s take on the raga is a must read. One will find that his observation as to Kafi of Hindustani music would apply like a glove to Karnataka Kapi or pehaps to the fourth/modern Kapi and I quote him verbatim, to conclude this blog post:

“Kafi is accorded a great deal of latitude in the interest of ranjakatva. In all kshudra ragas, ‘contamination’ on account of swaras not part of their intrinsic makeup is par for the course. A ‘pure’ version of Kafi is seldom heard in performance; almost all instances fall to the Mishra Kafi lot. With this understanding, here and in the ragas to follow, the explicit Mishra qualifier shall be dispensed with altogether. Bear in mind that strict conformity to etiquette is not expected of kshudra ragas.”

REFERENCES:

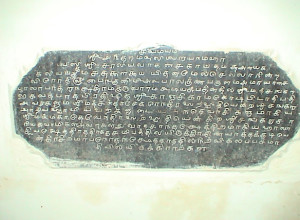

- Subbarama Dikshitar (1904)- Sangita Sampradaya Pradarshini – Published by the Madras Music Academy

- Prof S R Janakiraman(2002)-‘Ragas at a Glance’- Published by Srishiti’s Carnatica P Ltd, Chennai

- Hema Ramanathan(2004)- ‘Raga Lakshana Sangraha’- Published by Dr N Ramanathan, Chennai, pages 662-665

- Dr S Sita (1993) – “The Raga Lakshana Manuscript of Sahaji Maharaja” -Journal of the Madras Music Academy Vol LIV, pp 140-181, Madras India

- Dr N Ramanathan (2009)- “Ragas Rudrapriya, Karnataka Kapi, Kanada and Durbar- A Comparative Analysis”- Pages 103-114 Journal of the Madras Music Academy Vol 80, 2009

- Subba Rao & S R Janakiraman(1993) – “Ragas of the Sangita Saramruta” published by the Music Academy, Chennai

- Prof S Sambamoorthi(1970)- ‘Pallavi Sesha Iyer” – Article in ‘The Hindu’ dated 27th Jul 1970

- Govinda Rao T K (2002)- ‘Compositions of Maharaja Svati Tirunal’ published by Ganamandir Publications, Chennai

- K P Sivanandam(1964) – ‘Tanjai Peruvudaiyan Perisai’ – Compositions of the Tanjore Quartet, compiled by Sangita Kalanidhi T Ponnayya Pillai

- Sobhana Nayar (1989)- ‘Bhatkande’s Contribution to Music’ – Published by Popular Prakashan P Ltd, India ISBN 0 86132 238X

- Dr T S Ramakrishnan(1972) – ‘Venkatamakhin’s 72 Mela Scheme’ – Journal of the Music Academy Vol XLIV Pages 24-26, 61-83

FOOT NOTE 1: How did Kapi go extinct – A Hypothesis

During the period of 1600’s to late 1700’s, flavor 1 of Kapi held sway as evidenced by the kritis of Sesha Iyyengar, Virabadrayya and Srinivasayya. Flavor 2 perhaps coexisted into the late 1700’s. Despite being a famous sampurna raga then, it could not qualify as a raganga given the presence of Sriraga and it had to stay put under that clan.

Circa 1800- However with the onset of the 19th century, this Karnataka Kapi stood imperiled. Two new ragas were appearing on the horizon which proved life threatening. Probably by early 1800 – Kanada had started gaining ground. One can consider the evidence of the 2 Tyagaraja compositions namely Sukhi Evvaro and Sri Narada in Kanada. The period of 1800-1830 was perhaps marked by both the old Kapi and Kanada co-existing as evidenced by the kritis of Tyagaraja and of Dikshitar. Given Kanada’s dominance, flavor 1 Kapi probably cast off GMRS and morphed off into flavor 3 Kapi. The flavor 2 Kapi too went into oblivion as it could not sustain its melodic identity against the might of the Durbar. Durbar too sported GMRS and over the 1800’s, its GMRS morphed into GGRS, spelling the death knell for the flavor 2 Kapi.

In so far as the more traditional flavor 1 Kapi, Muthusvami Dikshitar or Svati Tirunal were perhaps the last to compose in this form of Kapi. One can even surmise that by that time (early 1800’s) it was on the verge of extinction and Dikshitar had attempted to resurrect it.

Flavor 3 Kapi derived out of the remnants of flavor 1 managed to survive between the 1800-1850 as evidenced by compositions of Svati Tirunal and the Quartet. The 1800’s also marked the rise of Kharaharapriya the full blown heptatonic melakartha, driven by the emergence of the Sangraha Cudamani and Tyagaraja’s prolific treatment of this raga through his kritis. And to Kharaharapriya, Kapi had to cede its scalar structure which resulted in Kapi losing almost all its melodic identity. Tyagaraja having composed in Kanada and Kharaharapriya might have composed in the old Kapi as well. We do have versions of kritis like Anyayamu Seyakura which is rendered both in Karnataka Kapi (flavor 1 or 3) and in modern Kapi or flavor 4.

The emergence of Kanada and Kharaharapriya meant that even the surviving flavor 3 Kapi had to go as it had little by way of melodic individuality to survive on its own. And so it went on to acquire 3 anya svaras namely kakali nishada followed by antara gandhara and suddha dhaivatha. The modern Kapi had now emerged ( by the latter half of the 19th century) from the skeletal remains of flavor 3 Kapi and today it exists ain a form much different to what it was once upon a time.

The life cycle that Karnataka Kapi underwent was probably also tied with the parallel evolution of the modern forms of the ragas Sahana, Durbar, Nayaki and Andhali. All of these ragas were at one point in time siblings along with Kapi under the Sriraga mela, sharing the motif GMRS and unique gandhara with kampita gamaka. They underwent a skeleton wracking transformation:

- Sahana gave up its sadharana gandhara, acquired a full blown antara gandhara with the result that it moved from the Sriraga clan into the Harikambodi/Kedaragaula melakartha/clan. As evidenced by the SSP, one can see that Sahana as captured by Subbarama Dikshitar sported both the gandharas and given the dominance of sadharana gandhara it was placed under the Sriraga mela. The notation of the kritis “vasi vasi” of Ramasvami Dikshitar, ‘Sri Kamalabikayam” of Muthusvami Dikshitar and the tana varna “Varijakshi” of Subbarama Dikshitar can be cited as concrete examples of the older Sahana.

- Durbar gave up its GMRS, acquired full ownership of the GGRS. The notation of the Dikshitar composition ‘Tyagarajad anyam najaneham” and that of Kuppusvami Ayya’s kriti ‘Sri venkatesvaruni’ found in the SSP and anubandha respectively can be cited as evidence for the older form of Durbar sporting GMRS.

- Nayaki too gave up GMRS and in lieu acquired an exclusive RGRS. The notation of the Dikshitar composition “Ranganayakam” and that of Tyagaraja’s ‘Dayaleni’ as found in SSP are evidences to this effect.

- Andhali which was during the times of Venkatamakhi under Sriraga mela, gave up its sadharana gandhara and moved to Kedaragaula mela. The notation of the Dikshitar kriti “Brihannayaki varadayaki” and the rendering of the kriti with sadharana gandhara by Smt T Brinda can be cited as authority for this. This has been discussed in an earlier blog post.

FOOT NOTE 2: Dikshitar’s 3 other kritis published by Sundaram Iyer

We have three more kritis in Kanada attributed to Dikshitar and published by Sundaram Iyer subsequently. They are ‘Veera Hanumate’, ‘Vishveshvaro’ and ‘Balambikaya param nahire’. This apart we have a kriti again in an admixture of Sanskrit, Telugu and Tamil starting as ‘Sri Maharajni’ which was discovered in the manuscripts of the Tanjore Quartet and published subsequently. The notations of the three compositions as published by Sundaram Iyer and their popular renderings seem to be aligned to modern Kanada rather than the Kapi documented in the SSP. It is indeed debatable whether Dikshitar composed in Kanada given that the raga is not found indexed in the Anubandha to the CDP and Subbarama Dikshitar too hasn’t given the raga in his SSP (though he mentions of a raga called Kanhra, which had gone out of vogue). Also in one of Sundaram Iyer’s publication it’s given that the raga name Kapi is synonymous with Kanada itself without any authority. A similar such reference is found in the Kritimanimalai of Rangaramanuja Iyengar.

In this section we take up just two of the kritis namely ‘Vishveshvaro Rakshatumam’ and ‘Balambikaya’.

The kriti “Vishveshvaro Rakshatumam” has most of its sahitya/lyric mirroring the Samavarali kriti of Dikshitar, “Brihadeesvaro’ documented in the SSP, making us look at this attribution with suspicion. Parking this issue aside ,we take a look at the presentation of this composition by Sangita Kalanidhi Semmangudi Srinivasa Iyer. In this undated concert he prefaces this so called samashti carana composition with an alapana and follows up with a few rounds of svaras. The interpretation in full has Kanada all over it.

Clip 8 : Sangita Kalanidhi Semmangudi Srivasa Iyer renders Vishveshvaro-Kanada

Vidushi Raji Gopalakrishnan renders the composition, “bAlAmbikAyA param nahIrE” in an AIR Navaratri Concert broadcast from the year 2007, accompanied by Vid Usha Rajagopalan on the violin, Vid Tanjavur Kumar on the mridangam and Vid Raman on the morsing

Clip 9 : Vidushi Raji Gopalakrishnan renders Balambikaayah-Kanada

Again the melodic material of this composition is all but modern Kanada. Both these compositions do not feature the raga mudra but sport the ankita ‘guruguha’.

Credits/Acknowledgements:

The clippings in this blog post have been used for purely educational purpose as illustration only and all copyrights therein lies with the performers or the music distributors.