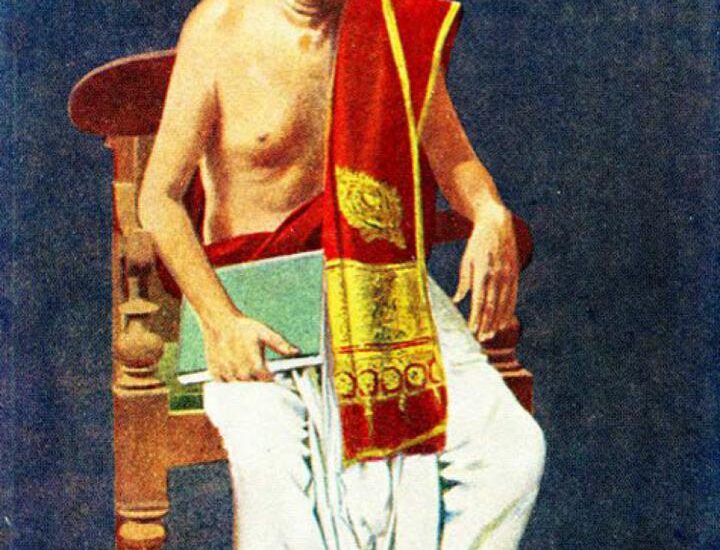

Manuscripts in the possession of Sivakumar, a descendant of Tanjavur Quartette

[simple-author-box]

Our music was propagated by two routes – oral and textual. Though we have a textual history of approximately 150 years recording the compositions of prominent composers, the corpus of compositions recorded by this way cannot said to be complete. Also, many compositions exist only in paper as they are not extant in the oral tradition. The converse is also true. Despite this extensive recording, many compositions have not seen the light and remain only in manuscripts and are yet to be published.

Tanjōre Quartette or Tanjai Nālvar as they are fondly called, hail from a family of rich musical heritage with their father and grandfather adorning the court of Maraṭṭa Kings. Cinnaiah (1802), Ponniah (1804), Śivānandam (1808) and Vațivēlu (1810) were born to Subbarāya Naṭṭuvanār, who was delegated to perform musical rites in Tanjāvūr Bŗhadīsvara temple. They were prodigious even at their young age and learnt the basics from their father and grandfather Gaṅgaimuttu Naṭṭuvanār. Later they had their advanced training from Muddusvāmy Dīkṣitar for a period of 7.5 years under ‘gurukulavāsam’.

We do not have exact details regarding the period of their stay with Dīkṣitar. But it can be presumed, these events could have happened during 1810-1820. Nālvar being exceptional musicians and related to a family having a hoary tradition related to classical dance, turned their focus towards Sadir (as it was called) and created a mārgaṃ, which is still followed. They have authored innumerable kṛti-s, padam-s, varņam-s, jāvaỊi-s, rāgamālikā and tillanā-s. Their compositional style for kṛti-s considerably differs from their dance compositions. It is said Nālvar has recorded their compositions and uruppaḍi-s they have learnt from Dīkṣitar in palm-leaf and paper manuscripts.

This family has given us illustrious musician-composers like Sri K Ponniah Pillai, Veena Vidvan Sri KP Śivanandam, who belong to the sixth and seventh descendant respectively from Gaṅgaimuttu Naṭṭuvanār, through the lineage of Śivanandam (of Tanjai Nālvar). These members are not only involved in the transmission and propagation of the compositions of Nālvar, but also involved in the preservation of these manuscripts.

These manuscripts are now, in the possession of Sri Śivakumār, an eight generation descendant and a proficient Veena and Violin vidvān. It is due to the persevering effort of this family, some of the unpublished compositions of Nālvar saw the light.

Paper manuscripts

Śivakumar has, in his possession several bundles of paper and palm leaf manuscripts. Though the palm-leaf manuscripts are under good condition, paper manuscripts require immediate attention.

Of the paper manuscripts available, a segment of a manuscript replete with the kṛti-s of Tanjai Nālvar and Muddusvāmy Dīkṣitar are considered now. Though, the report cannot be considered as complete, this can definitely give us an idea about the repertoire of Nālvar.

As with any other manuscripts written before the advent of standardized notations, notational style is primitive; lacks a mark to identify sthāyi, anya svaram and ending of an individual āvartanam. Also, these notations do not indicate about second and third speed. Rāga names too was not mentioned for many kṛti-s. Savingly, svarasthāna and the parent mēla of the rāga are given clearly alongside the notations.

The available material can be divided into three segments based on the composer:

- Kṛti-s of Nālvar

- Kṛti-s of Muddusvāmy Dīkṣitar

- Others

- Kṛti-s of Nālvar

In the section analyzed, Guru-navaratnamālika kṛti-s are seen with notation. This set of 9 compositions was composed by Nālvar as a Guru stuti. This cannot be considered as a regular Guru stuti. Nālvar invoke their Lord Bŗhadīsvara and they are not paeans composed on their Guru. Very few direct references to their Guru or his personality can be seen. These are to be compared and contrasted against the Guru kṛti-s composed by Vālājāpeṭṭai Vēṅkataramaṇa Bhāgavatar and/or other disciples of Tyāgarāja Svāmigaḷ.

Navaratnamālika of Nālvar

The following kṛti-s are held at high esteem due to the reasons mentioned above:

Māyātīta svarūpiņi – MāyāmālavagauỊa

Śrī guruguha mūrti – Bhinnaṣaḍjam

Sāṭilēni guruguha mūrtini – Nāța

Śrī karambu – Kanakāmbari

Sārekuni – Cāmaram

Śrī rājarājēsvari – Ramāmanōhari

Paramapāvani – VarāỊi

Sārasākși – Śailadēsākși

Nīdu pādamē – PantuvarāỊi

Two interesting observations can be made from this list. First, the rāga of the kṛti-s sāṭilēni and śrīkarambu is different from the present renditions. Now they are sung in the rāgam PūrvikaỊyāņi and Kāmbhojī respectively. Second, all the kŗtis-s are set in the “Rāgāṅga rāgā-s” (a term equivalent to the term mēḷakarta, usually referred to the scales in the asaṃpūrṇa mēḷa system). Pantuvarāli is specifically mentioned as a rāgam with sādhāraņa gāndhāra. This is in line with the old practice of calling the present day Śubhapantuvarāli as Pantuvarāli. This was remarked by Subbarāma Dīkṣitar too in his Prathamābhyāsa Pustakamu.

We also can see other kṛti-s of Nālvar in other rāgāṅga raga-s namely bṛhadīśvara in Gānasāmavarāli and bhakta pālana in Phēnadyuti. This totals to 11 kṛti-s belonging to this category. This makes us to surmise that Nālvar could have composed in all the 72 rāgāṅga rāga-s following the footsteps of their Guru. It is emphasized again that the manuscript referred here represents only a portion of their collection and the entire corpus is to be analyzed to get a definitive conclusion.

Though, an in depth analysis of the version given in this manuscript and the other printed versions is to be done, namely “Tanjai Peruvudaiyān Perisai” and “Saṅgīta Saṃpradāya Pradarśini”, the two authentic texts which give these kṛti-s (either all or a few) in notation, preliminary analysis revealed a significant finding which is worth discussing here. The version given here for the Māyātīta svarūpiṇi is exactly the same as given in Saṃpradāya Pradarśini !! There might be subtle differences which are trivial and some allowances need to be given considering the fact we are dealing with a manuscript.

Another interesting finding is related to the kṛti, “śrī rājarājeśvari” in the rāgam Ramāmanōhari. The version given in this manuscript has phrases like PRRSNN, PNS which are not seen in both the books mentioned though the version given by Subbarāma Dīkṣitar closely follows the manuscript excluding the presence of the mentioned phrases. Though, these phrases appear to be outlandish in Ramāmanōhari, they feature in a gītam notated in Saṅgīta Saṃpradāya Pradarśini. This shows Saṅgīta Saṃpradāya Pradarśini is a veritable source to know the rāga structure of the by-gone centuries. One more noticeable feature seen in these manuscripts is the total absence of ciṭṭa svāra segment for all the kṛti-s, irrespective of the composer involved.

Three other kṛti-s found in this manuscript deserve a special mention – Sarasvati manōhari gauri, Śrī jagadīṣamanōhari and Śrī mahādēvamanohari. Rāgā-s are not marked for these compositions. The kṛti śrī mahādēvamanohari was published in the book “Tanjai Peruvudaiyān Perisai” by the descendants of Tanjai Nālvar with a slight variations in the sāhityam. Whereas their version starts as mahādēvamanohari, the manuscript adds a prefix ‘śrī’ to mahādevamanōhari. Adding ‘śrī’ satisfy the rules of prosody as anupallavi reads as ‘sōmaśekhari’. Dhātu of this composition, as given in this manuscript too give us an interesting finding. Dēvamanōhari described in the treatises belonging to 17-19 CE whose authorship is known always stress the phrase PNNS and a straight forward DNS was never accepted by them. PNNS can be seen only in the version given in these manuscripts.

Rāga of the other two kṛti-s is to be determined. Rāgam of the first kṛti can be presumed to be Gauri as Nālvar had the practice of incorporating the raga mudra in many of their sāhityam. The notation will be analyzed and updated.

Beside these kṛti-s, varṇam-s like viriboṇi and mā mohalāhiri are seen.

2. Kṛti-s of Muddusvāmy Dīkṣitar

Around 90 compositions can be identified to be that of Dīkṣitar and all are available with notations. Out of these 90, 5 are unpublished. The remaining 85 can all be seen in Saṅgīta Saṃpradāya Pradarśini of Subbarāma Dīkṣitar. As mentioned earlier, the kṛti-s seen in this small portion of the corpus cannot be considered as the complete repertoire of Nālvar. Nevertheless, 85 denotes a significant number and it is to be borne in mind that not even a single composition seen here is outside Saṃpradāya Pradarśini. This shows any kṛti not mentioned in this text is always to be taken with a grain of salt.

A. Majority of the kṛti-s in the majority 85 belong to the clan of ”Rāgāṅga rāga-s”. Kṛti-s of Dīkṣitar can be seen in all the rāgāṅga rāgā-s except for ten. They include Toḍi (8), Bhinnaṣaḍjam (9), Māyamālavagaula (15), Varāli (39), Śivapantuvarāli (45), Ramāmanōhari (52), Cāmaram (56), Niṣada (60), Gītapriyā (63), Caturaṅgiṇi (66), Kōsalam (71). It is to be remembered here that Saṅgīta Saṃpradāya Pradarśini too didn’t furnish the kṛti-s of Dīkṣitar in the rāga-s 9, 45, 52 and 56. Of these four, a kṛti of Ponniah (of Nālvar) was given for three rāga-s – 9, 52 and 56. Śivapantuvarāli was not awarded with any kṛti. Same pattern was followed in this manuscript too. Kṛti-s were given in order of the rāgāṅga raga. After the rāgāṅga rāga 7, we find the kṛti of Nālvar in the rāgam Bhinnașaḍjam (śrī guruguha mūrti) followed by a kṛti of Dīkṣitar viśvanātham bhajēhaṃ in the rāgāṅga rāgam Naṭābharaṇam (10). This pattern is being followed for the rest too [after Bhavānī (44), Kāśirāmakriyā (51) and Śyāmaḷā (55) we find a kṛti of Ponniah in 45, 52 and 56 followed by a kṛti of Dīkṣitar]. Blessed is Śivapantuvarāli to have a kṛti of Nālvar in this manuscript. This raises a doubt on the authenticity of the Dīkṣitar kṛti-s presently prevalent in the rāga-s 9, 45, 52 and 56.

It is to be accepted that we don’t find a kṛti of Dīkṣitar in others rāgāṅga rāga-s namely 15, 60, 63, 66, 70 and 71. Excluding 15 and 39, the rāga-s preceding and succeeding these left–outs do not occur in sequence. They occur haphazardly; perhaps they might have been written separately and those pages are lost. 15 is an exception here as it is seen in sequence succeeding Vasantabhairavī (14) and preceding Vegavāhini (16). Reason for māyātīta svarūpiṇi replacing śrīnāthādi is not clear. But, it could have been separately written and lost. We have another example to support this view – the kṛti bhajarē citta in Kaḷyāṇi (65) is found separately and not after Bhūṣāvati (64). We find only one kṛti in Kamalāmbā navāvaraṇam (śri kamalāmbikayā in Śaṅkarābharaṇam) and three in Navagraḥa series, namely divākaratanujam, bṛhaspate and sūryamūrte. Reason for not seeing any entry in 39 is an enigma.

B. It can be noticed, after the rāgāṅga raga 7, we see a kṛti of Ponniah in the rāga 9. Rāga 8, Tōḍi does not have any entry. Can we presume Kamalāmbike was the only kṛti composed by Dīkyṣitar in Tōḍi before and/or during his stay in Tanjōre and due to some reasons that was not notated ? Either that was not known to Nālvar or that was composed by Dīkṣitar after his stay in Tanjōre ? Alternatively, was that notated separately and yet to be identified ? But not seeing a composition in such a major rāga is strange.

C. Regarding grouping a rāga under a mēla, this manuscript conforms with the grouping system followed by Subbarāma Dīkṣitar. Āndāḷi is given under mēḷa 28 and Sāma under 29. The only exception to this is Saurāṣtram; considered as a janya of Vēgavāhini in this manuscript. This is understandable due the presence of anya svaram in this this rāgam.

D. Four kṛti-s belonging to Guruguha vibhakti kṛti-s are seen – śri guruguha mūrtē in Udayaravicandrikā, śri guruguhasya dasōham in Pūrvi, guruguhādanyam in Balahaṃsa and guruguhāya in Sama. Bhānumati, though a rāgāṅga rāgam is represented only by the kṛti ‘bṛhadambā madambā’ and not ‘guruguha svāmini’.

E. None of the kṛti-s belonging to Tyāgarāja vibhakti group can be seen. Does it mean these kṛti-s were composed after his stay in Tanjōre ?

F. Almost all the kṛti-s addressing Bṛhannayaki or Bṛhadīśvarar, notated in Saṅgīta Saṃpradāya Pradarśini are seen here.

G. Mīnākṣi mēmudham dēhi is seen in this manuscript suggesting this kṛti must have been composed when he visited Madurai before his stay in Tanjōre.

H. Minority 5 is much more interesting. We see these compositions for the first time. They appear to be a part of Nirūpaṇam than kṛti-s. They include:

Jaya jaya gauri manōhari – 22 janyam (to be identified)

Kāmakṣi namōstute – Pāḍi

Śaranu kāmākṣi – Mēgarañjani

Manōnmaṇi bhavatutē maṅgaḷam – Mēcabauli

Śaranu śaranu mahēśa śaṅkari – Ārabhī

Of these, the first three has been mentioned by Dr Rīta Rājan in her thesis.

A reconstructed version of the Śaraṇu daru – ‘śaraṇu śaraṇu’ in the rāgam Ārabhī can heard here

I. Though, an in-depth comparison is to be done with the version given by Subbarāma Dīkṣitar, at the outset, can be confidently said not much difference exist between the two.

3. Others

Other than the works of Dīkṣitar and Nālvar, we also find padam-s of Kṣetrayya and some other kṛti-s of unknown authorship. Sri Śivakumar also possess another paper manuscript having around 300 gītam in notation. Examination of a sample showed that they are the replica of the gītam-s notated in Saṅgraha Chūḍāmaṇi. This could been written by some other member in the family.

Conclusion

This inventory is not complete and highlights only some important findings seen in a section of a major collection. It is believed these findings will be more helpful to the researchers and musicians alike to get an idea about the Dīkṣitar kṛti-s learnt by Nālvar. When these kṛti-s are compared with the versions given by Subbarāma Dīkṣitar, we can get an overall image about the melodic structure of Dīkṣitar kṛti-s in general. This might be of some help In clearing the controversies revolving around these kṛti-s. Some other points in identifying the ‘real’ Dīkṣitar kṛti too is highlighted so that these findings can be applied or recollected when we progress further and get some additional material.

Acknowledgement

I profusely thank Sri KPS Śivakumar, an eighth generation descendant belonging to the family of Nālvar and the son of Sangīta Kaḷānidhi Sri KP Śivānandam for sharing these valuable manuscripts.

Excellent write up sir.

Nice work..