Nishumbasudani……. Mystery from the medieval Chola times!

Prologue:

More than 14,000 Kms away from Tanjore in Southern India, half way across on the other side of earth is the American city of Philadelphia. A discerning lover of Indian art, residing in or near this city should definitely make that visit to the Philadelphia Museum of Art. As a visitor goes to the Museum’s second floor which houses its South Asian collection of art, the most eye catching would be the Hall reassembled on site from remnants of the Madana Gopala Swamy Temple, Madurai which was shipped out of India circa 1912 AD, by a wealthy Philadelphian Ms Adeline Pepper Gibson. While the antiquity of this Hall is just around 500-600 or so years only , in the room adjacent to this Hall, away from the spotlight would be the still older Chola artworks on display dating a further 500 years prior. And amongst the works of arts there, a discerning visitor can spot an icon of Goddess Durga or more specifically one should say, ‘nisumbhasUdanI’ or the Slayer of the demon Nishumbha, on display. A look at the card tagged to this bas relief would state its antecedents briefly as “Goddess Durga As the Slayer of the Demon Nishumbha (Nishumbhasudani), 900 to 925 CE, Tamil Nadu, India”.

A closer analysis of this sculpture would reveal that it is a 10th Century granite bas relief, albeit a little damaged, but nevertheless a masterpiece from the times of the medieval Cholas. We do not know from whom and where this icon was sourced from, but the Museum has this item in its Collection having purchased it from out of the funds of the Joseph E Temple Trust in the year 1965. This Devi, the slayer of Shumbha, Nishumbha and Mahishasura is the subject matter of this blog post.

Actually, the blog is about two mysteries, dating back to centuries prior which continue to hold us in thrall. And this Devi, ‘nishumbhasUdanI’ is the link with which we will look at these two mysteries. We have very few facts or solid information from those times, long bygone and this blog is to place them in proper perspective as always to provide a context for a raga and a composition. This blog has been written, alternating between the two mysteries while at the same time providing some background then & there for which foot notes have been written so as to provide continuity.

Read On!

Introduction:

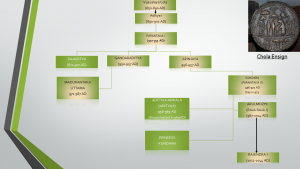

The Cholas were the great Kings of southern Tamilnadu ruling from Tanjore. The subject matter for us are the Medieval Cholas who ruled first from Uraiyur and later from Tanjore between 848 AD and 1070 AD. The Chola Kings who ruled prior are called the Early Cholas and those who ruled after 1070 AD are called the Later Cholas by historians. Very well known in this lineage of medieval Chola Kings are Emperor Raja Raja I (whose actual name was Arulmozhi Varman) and his son Rajendra I who respectively constructed the Brihadeesvara Temple at Tanjore and its look like, the Great temple at Gangaikondacholapuram.

The first King of this medieval Chola lineage was Vijayalaya Chola (regnal years 848 AD-891 AD) who is also credited to have founded the modern city of Tanjore, making it the Capital of the Imperial Cholas. When he laid the foundation of this great Chola lineage and that of the City of Tanjore as his capital, legend has it that he made the icon of Goddess Durga or ‘nishumbasUdanI’ as the tutelary deity of the Cholas. She was revered as a war Goddess and legend has it that Vijayalaya built a temple for Her in Tanjore. Historians are unanimous in their opinion that this Temple no longer exists today. The only reference to this act of Vijayalaya Chola and vouching for the existence of Nishumbasudani is this following verse found in the Tiruvalangadu Copper plate (see Note 1) which in a set of verses, in the nature of hagiography, detailing the entirely lineage of Cholas as a brief history.

தஞ்சாபுரீம் ஸௌத ஸுதாங்காராகாம்

ஜக்ராஹ ரந்தும் ரவிவம்ச தீப:

தத:பிரதிஷ்டாப்ய நிசும்ப சூதனீம்

ஸுராஸுரை:அர்ச்சித-பாதபங்கஜாம்

சது : ஸமுத்ராம்பர மேகலாம் புவம்

ரஹாஜ தேவோ தத்பராசதந”

(Verse 46 of the Tiruvalangadu Copper Plate – History of the Cholas- See Note 2)

Meaning: Having next consecrated (there at Tanjore) (the image of) Nisumbhasudani whose lotus-feet are worshipped by gods and demons, (he, Vijayalaya Chola) by the grace of that (goddess) bore just (as easily) as a garland (the weight of) the (whole) earth resplendent with (her) garment of the four oceans.

And this Goddess Nishumbasudani as the tutelary deity of the Cholas becomes our object of attention. And consecrated in that Temple at Tanjore around 850 AD she must have overseen the rise and the fall of the medieval and later Cholas, spanning about 400 years thereafter before she herself probably disappeared from our view. Let us fast forward time by about 100 years to the reign of Vijayalaya’s grandson’s grandson Parantaka Sundara Chola or Parantaka II of the historians for a peek at a mystery which has for a very long time held the attention of Tamil historians, researchers and literary readers.

Circa 957 AD

Parantaka Sundara Chola, a descendant of Vijayalaya, ascended the Chola throne in 957 AD. His father Arinjaya Cola had earlier ruled for a brief period succeeding his own elder brother Gandaraditya. Since Gandaraditya died leaving a very young son (Madurantaka Uttama), Arinjaya ascended the throne and he also having died shortly thereafter, it became inevitable that Parantaka Sundara the son of Arinjaya ascended the throne as Madurantaka Uttama was still a minor. Nevertheless, given the patriarchal line of succession as was prevalent, Parantaka Sundara thus became King even while his father’s elder brother’s son Madurantaka Uttama, being the rightful claimant to the throne was there. We do not know the intrigues that went on in relation to this succession but nevertheless the same becomes a key pivot for the proceedings.

Parantaka Sundara’s eldest son was Prince Aditya Karikala (See Note 3) who records say was anointed as Crown Prince. And it was not Madurantaka Uttama the older claimant. We do not know, as between Aditya Karikala and Madurantaka Uttama who was elder by age but it was Aditya Karikala who became the heir apparent. Parantaka Sundara’s two other children were Prince Arulmozhi Varman and Princess Kundavai who would have been yet another set of siblings to the anointed Crown Prince Aditya Karikala, without any right to inherit the throne, but for the chain of events that were about to engulf Tanjore shortly thereafter, a veritable Game of Thrones, a medieval version at that, which brought these two younger royals to the forefront.

Even while Parantaka Sundara Chola ruled over from Tanjore, by 965 AD it was left to the young & mighty Crown Prince Aditya Karikala to expand the frontiers of the Chola Kingdom. Records say that he decimated the Pandyan army at the Battle of Sevur (near Pudukottai) and killed King Veerapandya earning for himself the title ‘The Vanquisher who took the Head of Veerapandya’ (‘vIrapAndiyan thalai konda parakesari’). Even the Thiruvalangadu copper plate verse No 68 too makes a mention to that effect, Dr Nilakanta Sastri opines that Aditya would have not literally done so and the said epithet was just to signify his victory over Veerapandya. The true import of this epithet would prove important later when we come to interpret the happening that would shake the very foundation of the medieval Chola rule.

Given the perpetual rivalry between the Cholas and Pandyas, a victory of that proportion must have been a truly momentous occasion. But that victory was to turn a pyrrhic one. It is well likely that Madurantaka Uttama, the cousin of Parantaka Sundara, the reigning King upon attaining majority must have nursed ambitions to be the next King given the precedence of his claim to the throne. However, given the legendary & heroic exploits of the Crown Prince Aditya Karikala, Madurantaka Uttama’s claim would have likely been eclipsed by Aditya’s. Whether Madurantaka Uttama resented it and whether directly or indirectly he advanced his claims or wishes to ascend the throne, we do not know. In the same breath it has to be said that we do see inscriptions wherein Madurantaka Uttama is recorded as a Prince (if not as a Crown Prince) performing his royal duties in his own right during the reign of Parantaka Sundara Chola, such as the one at Tiruvottriyur, (Udayar is the tamil word which is used as a prefix to the Prince in the said inscription).

While all was well this far in Tanjore in the early months of 969 AD with Parantaka Sundara as King and Aditya Karikala as the Crown Prince & successor designate, let us leave the dramatis personae for a while and fast forward quickly to the present.

21st Century:

The Nishumbhasudani Goddess Durga icon which we one can see in the Philadelphia Museum, dateable to 900 AD, being the reign of Vijayalaya Chola or his successor Aditya I sets us thinking if it is perhaps from that very Temple which was constructed at Tanjore for Her by Vijayalaya and which today is just a legend. May be or maybe not, nevertheless the reference to the Nishumbhasudani Goddess Durga and that mythical temple would certainly encourage one to search for a reference to Her and the temple in our musical or literary heritage left behind by the poets, composers and savants of the past. However, a diligent search for Her seems to show no trace of any verse or reference or composition or any epigraphical record pointing us to this Devi. In sum, save for the solitary reference in the above referred Thiruvalangadu Copper plate to this Nishumbhasudani of Tanjore. Also the existing structures and temples in Tanjore for Goddess Durga too seem to have been much later constructed temples. See Note 4. Where was this Goddess who had as her abode the temple constructed by Vijayalaya Chola ?

In passing, it is worth mentioning that readers of Kalki’s classic ‘Ponniyin Selvan’ would doubtlessly recall the references to Goddess Durga Parameswari and also the allusion to this Devi’s Temple in the proceedings in the said work.

While this is so let’s move the clock back this time by just around 200 plus years to first two decades of the 19th century, when Muthusvami Dikshitar the itinerant composer spent some time at Tanjore.

Circa 1800 AD:

Biographers of Muthusvami Dikshitar (1775-1832 AD) refer to an extended period of time when he visited and stayed in Tanjore. His prime disciples namely the Tanjore Quartet being Ponnayya, Chinnayya, Sivanandam & Vadivelu when they were in the Court of Serfoji II, are said to have invited him to be with them and he reportedly obliged them by doing so sometime during this period. It was during this sojourn that Dikshitar at the request of the Quartet, commenced the project of investing a composition in every one of the 72 mela ragas of the compendium of Muddu Venkatamakhin. Even while as Dikshitar embarked on creating a number of them on the deities of the very many temples and around Tanjore, could he have created one on Nishumbasudani Goddess Durga? None of the biographers of Muthusvami Dikshitar attribute any kriti to Her and therefore one in left with their own devices to investigate if any kriti can be ascribed to this long-lost tutelary deity of the Imperial Cholas.

It does make one surmise whether Dikshitar would have craved to have a darshan of this great & hoary deity. He must perhaps got himself satisfied by visiting and paying obeisance to Her at the smaller shrine in the then ramparts of the Tanjore fort. Could he have perhaps having heard of this mythical yet fearsome war Goddess wondered where on earth she was and then hearing about the futility of discovering Her or the legendary temple, perhaps went on to eulogize her, invoking her imagery with his inner vision and thus creating a composition? If indeed there was one kriti at the very least we can surmise that it could be the one he might have composed on this Nishumbhasudani. And that composition could surely be a pen picture of that great Devi, which we can perhaps use as a proxy to that long-lost icon.

In other words, could Dikshitar have created a composition on that mythical Goddess just as how he had done for the mythical Goddess Sarasvati of Kashmir or the One who resided on the banks of the mythical Sharavati river, without having visited Her? And if he had composed one, which is the raga of choice Dikshitar would have employed? Before we progress further we must note one caveat here. In the first place we have attempted to search for this supposed composition on Nishumbhasudani, as there were no already attributed compositions to start with, with the embedded ksetra/stala or any other internal/external evidence. We have embarked on this only to surmise on the possible composition which could have been created by Dikshitar on this mythical Goddess of Tanjore and therefore for sure the composition will be bereft of any evidence to that effect.

In so far as the raga of the composition, it is entirely in the realm of possibility that Dikshitar must have applied great thought to the choice of the raga. And perhaps given his predilection for the rare and the archaic, he must have proceeded to compose the same in a long-forgotten raga, but which would have ruled the roost centuries ago and had been forgotten by 1800’s.

Thus, a composition in a long forgotten archaic raga for a mythical and again completely forgotten tutelary deity of the great Cholas of Tanjore would have been his complete and appropriate homage to that Nishumbhasudani. And could he have done it?

Having surmised a case for a probable composition of Muthusvami Dikshitar, on the Nishumbhasudani of Tanjore, it is time for us to go back to the times of Sundara Parantaka Chola once more.

Circa 969 AD

The year AD 969 would have been King Parantaka Sundara Chola’s 12th year of reign and his Crown Prince & anointed successor Prince Aditya Karikala must have been around 22 years old. And then sometime September that year, tragedy strikes the Royal Cholas.

The Tiruvalangadu Copper plates mourn the death of the young Crown Prince Aditya Karikala with the verse no 68 running thus:

Having deposited in his (capital) town the lofty pillar of victory (viz.,) the head of the Pandya king, Aditya disappeared (from this world) with a desire to see heaven.

In essence the copper plate records, bemoaned the setting of the sun (“Aditya”) probably plunging the entire Chola kingdom in grief & darkness. It must be noted that Tiruvalangadu plates (which by themselves were created during the reign of Rajendra Cola, circa 1030 AD or more than 50 years or so later from this event) as above merely mention this untimely demise and it does not raise the sceptre of assassination or foul play in his death. Neither was there any war or battle on record in which the valiant Prince could have lost his life, at that point in time. And if so the epigraphs would have eulogized his death much like how his paternal uncle Rajaditya was. It is only the inscription at Udayarkudi (created later during the reign of King Raja Raja Chola, circa AD 1010) which throws further light on this mysterious tragedy. The said inscription attests to the assassination of Crown Prince Aditya Karikala, implying that three brothers Soman Sambhavan, Ravidasan alias Panchavan Brahmadhirajan and Parameswaran alias Irumudichola Brahmadirajan being traitors, had been instrumental in the death of the Crown Prince. Modern historians opine that one or more of these three personalities were high ranking Chola Officials who were insiders to the regime and most probably they took revenge on the Crown Prince for the death of the Pandyan King and after doing the foul deed they probably fled for life, for we have no record of them having been caught, tried and sentenced. The Udayarkudi inscription unambiguously makes it know that the assassins and their relatives were banished and their assets confiscated by the State. Nothing is known further than this.

From inscriptions or the Chola era copper plates, nothing further is known as to how and where Crown Prince Aditya Karikala was killed even while different theories have been floated about both by historians and fiction writers in the 20th century. Be that as it may, the Royal House of the Cholas must have plunged into grief with the death of its Crown Prince. Tongues must have wagged and the loyalties of the members of the Royal Family and Courtiers must have been called into question. (See Note 5)

And thus, ended the life of Crown Prince Aditya Karikala some 1050 years ago in 969 AD. In his death perhaps unwittingly lay the glory of the Imperial Cholas. His brother Raja Raja I and thereafter his successor Rajendra I went on to become the great Emperors of Southern India expanding their influence even into modern day Malaysian peninsula and the Indonesian archipelago. And for these Chola Kings their tutelary deity Nishumbhasudani was always the greatest benefactor and guardian angel in whom they reposed undiminished faith, so much so that even the Mahratta Kings who came to rule from Tanjore much later, in a bid to capitalise on the same faith and authority as the Imperial Cholas, too made Her as their family deity. The medieval Chola history thus leaves amongst many others, chiefly two unsolved mysteries or questions for us today. First being the unsolved death of the young and chivalrous Crown Prince Aditya Karikala in AD 969 and secondly the whereabouts of the Nishumbhasudani icon and the temple venerated by them which was once upon a time in Tanjore.

And with these questions open, we will take leave of the Chola Royals and move on quickly some 800 years hence immersing ourselves now in matters musical.

Circa 1800 AD

As we surmised earlier if indeed Muthuswami Dikshitar had composed a kriti on this Nishumbasudani of Tanjore, it ought to be documented in the magnum opus Sangita Sampradaya Pradarshini (SSP) of Subbarama Dikshitar for sure. A perusal of Dikshitar’s compositions therein quickly reveals one which satisfies our query, the composition starting ‘mahishAsuramardhini’ in the raga Narayani under mela 29 Sankarabharanam.

We had further surmised earlier that the raga of the composition, if one exists is likely to be an archaic one. And Narayani is truly one. Before we deep dive to examine this statement, one omnibus declaration needs to be flagged right away. The raga tagged as Narayani by the Sangraha Cudamani with two Tyagaraja compositions as exemplars are certainly not Narayani. Again, as pointed out earlier the scale as exemplified by these two Tyagaraja composition has been wrongly assigned the name Narayani. It is a different raga altogether.

Narayani’s History:

The Narayani of Muthusvami Dikshitar as illustrated in the SSP (1904 AD) on the authority of the Anubandha to the Caturdandi Prakashika (circa 1750 AD) claims a hoary lineage all the way tracing back centuries prior, as a raga taking only the notes of Sankarabharana/29th mela of our present day Mela system. Ramamatya’s Svaramelakalanidhi ( 1550 AD) Poluri Govindakavi’s Ragatalachintamani ( circa 1650), Ragamanjari of Pundarikavittala ( circa 1575), Govinda Dikshitar’s Sangita Sudha ( AD 1614), Venkatamakhin’s Caturdandi Prakashika ( 1620 AD), Sangita Parijata of Ahobala ( 17th century), Srinivasa’s Ragatattva Vibhoda ( 1650AD), Sahaji’s Ragalakshanamu ( 1710 AD), Tulaja’s Sangita Saramruta ( 1732 AD) and finally ending with Muddu Venkamakhin’s Anubandha, all these musical texts unequivocally & in unison assert that the Raga Narayani takes the notes of Mela 29 /Sankarabharanam. It is indeed incomprehensible how this hoary raga which has been so for centuries under Sankarabharana mela can be classified under Harikambhoji mela (as in Sangraha Cudamani).

Without much ado one simply needs to cast aside/discard the aberrant definition laid down for raga Narayani by the Sangraha Cudamani and proceed to evaluate the history and the lakshana of the raga as laid down unanimously by all previous musicological treatises or more precisely by the Triad – being the works of Sahaji (AD 1710), Tulaja (AD 1732) and Muddu Venkatamakhin (AD 1750) and proceed to draw the conclusions therefrom. We have seen time and again that the lakshana of a raga as given by this Triad together with the exemplar kriti of Muthusvami Dikshitar as documented in the SSP would enable us to understand the true and correct picture of the raga. In the current context, we also need to evaluate why Narayani is archaic and went extinct. It is a fact that neither this Dikshitar kriti ‘mahishAsuramadhini’ nor any other kriti conforming to the Narayani of the 29th mela is even encountered on the concert circuit today.

But firstly, lets evaluate the lakshana of Narayani according to Sahaji, Tulaja and offcourse Muddu Venkatamakhin.

Lakshana of raga Narayani & likely why it went extinct:

The Triad of musicological texts and the kriti of Muthusvami Dikshitar provides us the following lakshana of the raga:

- The raga is sampurna, i.e all seven notes of mela 29 occurs in this raga.

- It is upanga in the modern as well, i.e it takes only the notes of mela 29 being R2, G3, M1, P, D2 and N3

- SRGM, PDNS, SNDP – these lineal combinations do not occur. Though MGRS is permitted by the definition the Dikshitar kriti sports only MG\S only, with the rishabha occurring more as an anusvara.

- It is a raga with vakra/ devious progression sporting RMGP, SMGP, GPD, GPDr, PMGS, SNDS, SNPD, DNP, SNP and MGPD as evidenced in the kriti of Dikshitar. Its perplexing that Subbarama Dikshitar provides two murcchanas SRMPNDS and GRSndS, which are not seen in the kriti and which would give a different melodic complexion to the raga, though GRSndS seems acceptable.

- In modern parlance SRMGPNDS or better still SMGPDNPDS /SNPNPDMPMGS can be notional arohana/avarohana krama.

- Needless to add that it is a quintessential raga aligning perfectly to the classic 18th century raga architecture with jumps, bends, turns and twists on one hands & multiple arohana/avarohana progressions as well. MGPD, MG\S seem to be the recurring leitmotifs.

The evaluation of the raga’s contours would show that it has considerable melodic overlap with modern day Bilahari. Bilahari is a much newer raga in comparison to Narayani for it is documented for the first time only by Sahaji in his work, circa 1710 AD. No prior musical work documents Bilahari. Given the subsequent popularity that Bilahari had gone on to acquire, Narayani must have ceded ground, giving up much of its musical material and thus became archaic.

In this context it has to be pointed out that modern musicological books wrongly provide Bilahari’s arohana plaintively as SRGPDS while it is actually SRMGPDS. And the raga Bilahari is bhashanga and takes the kaishiki nishada too in its melodic body which is attested for by Subbarama Dikshitar in the SSP. However, we see popular presentations of Bilahari shorn of these two features making us wonder if what is being sung today is only Narayani, of yore! This apart again, we do have some long lost prayogas of Bilahari which would impart a hue very different from what we hear today as Bilahari. The complete analysis of Bilahari rightfully belongs to another separate blog post which will done shortly.

In so far as the Narayani and Bilahari as delineated in the SSP, without doubt it can be stated that on the basis of the lakshanas as laid out in the Triad with the Dikshitar kriti as exemplars, one can sing the two ragas with their respective individual identities intact. However, to understand the correct melodic identity of these two ragas we have to necessarily set aside the incorrect text book lakshana of Bilahari as being presented today popularly and also ignore the aberrant ‘modern’ lakshana of Narayani which has been advanced on the strength of the Sangraha Cudamani, giving the two Tyagaraja kritis ‘rAma nIvEgani’ and ‘bhajanasEyu mArgamunu’ as exemplars. As pointed out earlier, the raga found in these two compositions is a different melody under Harikambhoji mela for which a new name should be identified and given so that no confusion is made between these melodies. Again, it is reiterated that Tyagaraja never assigned names to his ragas and it was only much after his life time, his lineage of disciples, publishers of his compositions and authors who compiled ragas, assigned raga names post 1850 AD, to his kritis. This misnaming of the melodies of Tyagaraja’s compositions using the older raga names and established identities such as Sarasvati Manohari, Narayani etc has resulted in this confusion where we have a single raga name for two melodies with different musical identities. It is regrettable that this state of affairs has been perpetuated this far.

Be that as it may, for this blogpost the record is set straight once more here by reiterating that the Narayani of yore was only a melody under Mela 29/Sankarabharanam taking only its notes (upanga in modern parlance) and the kriti of Dikshitar ‘mahishasura mardhini’ set in this raga is the sole exemplar.

Text and meaning of the lyrics of ‘mahishAsuramardhini’ in Narayani:

The kriti is in the classic Dikshitar format sporting both the raga mudra as well as his colophon. It is to be pointed out here that the section of the caranam commencing ‘shankarAdra sarIrinIm’ is in a pseudo-madhyama kala and is not at double the akshara count of the rest of the composition.

pallavi

namāmi – I salute

mahiṣa-asura-mardinIm – the destroyer of the demon Mahisha!

mahanIya-kapardinIm – the venerable wife of Shiva (who wears matted locks),

anupallavi

mahiṣa-mastaka-naTana-bheda-vinodinIM – the one who revels in performing different dances on the head of the buffalo-demon Mahisha

mOdinIM – the blissful one,

mālinIM – the one wearing garlands,

māninIM – the honourable one,

praNata-jana-saubhAgya-dāyinIm – the giver of good fortune to the people who salute reverentially,

caraNam

shankha-cakra-shUla-ankusha-pANIM – the one holding a conch, discus, trident and goad in her hands,

shakti-senāM – the one leading an army of Shaktis (goddesses),

madhuravāNIM – the one whose voice and speech are sweet,

pankajanayanāM – the lotus-eyed one,

pannagaveNIM – the one whose braid is (long and dark) as a cobra snake.

pālita-guruguhāM – the one who protects Guruguha!

purāNIm – the ancient, primordial one,

shankara-ardha -sharIriNIM – the one who has taken half the body of Shiva,

samasta-devatā-rUpiNIM – the one who is the embodiment of all the gods,

kankaNa-alankRta-abja-karāM – the one whose lotus-like hands are adorned with bangles,

kātyāyanIM – the daughter of Sage Katyayana,

nārāyaNIm – the one related to Narayana (being his sister).

In the context of the lyrics, specific attention is invited to the line sankarArdha-sarIrinIm samasta-devatA-rUpiniM, by which Dikshitar alludes briefly to how the conception of Goddess Durga is said to happened as recorded in religious texts.

Here is the link to the rendering of the kriti which has been rendered very close to the notation found in the SSP, by Sangita Kala Acharya Dr.Seetha Rajan. ( see Foot Note 6)

A Brief Note on one other composition attributed to Muthusvami Dikshitar:

While the SSP records only this Narayani composition ‘mahishAsura mardhini’, on Goddess Durga or her synonymous forms, Veena Sundaram Iyer during the 1960’s brought to light another composition (not found in the SSP), attributing the same to Muthuswami Dikshitar. The text of the same together with the meaning of the lyrics is as under:

mahishāsuramardini – rAgam gauLa – tāLam khaṇDa cApu

Pallavi

mahiṣāsura-mardhini māṃ pāhi madhya-deśa-vāsini

Anupallavi (samaṣṭi caraṇam)

mahādeva-mānasollāsini mā-vāṇI guruguhādi-vedini mārajanaka-pālini sahasra-dala-sarasija-madhya-prakāśini suruciranalini śumbha-niśumbhādi-bhanjani

(madhyamakāla-sāhityam) iha-para-bhoga-mokṣa-pradāyini itihāsa-purāNādi-viśvāsini gaurahāsini

Meaning:

mahiṣa-asura-mardini – O destroyer of the demon Mahisha!

māṃ pāhi – Protect me!

madhya-deśa-vāsini – O resident of Madhya Desha!

anupallavi (samaṣṭi caraṇam)

mahā-deva-mānasa-ullāsini – O one who delights the heart of Shiva (the great god)!

mā-vāṇi-guruguha-ādi-vedini – O one understood by Lakshmi, Sarasvati, Guruguha and others!

māra-janaka-pālini – O protector of Vishnu (father of Manmatha)!

sahasradaLa-sarasija-madhya-prakāśini – O one resplendent at the centre of the thousand-petal lotus!

suruciranaLini – O charming one, lovely as a lotus-creeper!

śumbha-niśumbha-ādi-bhanjani – O destroyer of the demons Shumbha and Nishumbha and others!

iha-para-bhoga-mokṣa-pradāyini – O giver of enjoyment and liberation for this world (iha) and the other (para), (respectively)!

itihāsa-purāṇa-ādi-viśvāsini – O repository of the faith of the epics and Puranas!

gaurahāsini – O one who has a shining white smile!

Keeping aside the question whether this composition truly is of Dikshitar based on its provenance, prasa, tala, meaning of some of the lyrics occurring in the composition, the mettu/musical setting of the composition etc two points arise for our consideration in the specific context of this blog post.

- The reference to the probable sthala of this composition – ‘madhya-desha-vasini’ occurring in the pallavi

- The reference ‘shumbha nishumbhAdi bhanjanI’ occurring in the so called samashti caranam or strictly in SSP parlance, anupallavi of the composition.

It has to be confessed that these points take us nowhere, as ‘madhya desa’ is certainly not Tanjore. The other reference as to Her as vanquisher of Nishumbha though relevant may not necessarily advance our case. The controversy as to the authorship of the composition coupled with the above factors, takes us no further forward and given that our objective is to merely speculate on the probable composition of Dikshitar on the mythical Nishumbhasudani of Tanjore, it is left to the reader to draw his own conclusions thereof. ( See Foot Note 7)

CONCLUSION:

With passage of every day, month, year and decade or century, the probability of finding any further evidence or epigraph or inscription which could potentially tell us of what truly happened to that mythical temple and icon of ‘nishumbhasUdani’ at Tanjore or what really happened that fateful day of 969 AD when Crown Prince Aditya Karikala was assassinated and who was behind that, keeps receding. Even Kalki Krishnamurthi in his classic read ‘Ponniyin Selvan’, keeps the mystery tantalizingly open, leaving it for the imagination of the reader for he felt that it would kill the suspense. (See Epilogue)

And for that event of 969 AD, that legendary Chola titular deity Nishumbhasudani had been a mute witness! And it was as if She too disappeared from the face of earth along with her Temple at Tanjore, constructed by Vijayalaya & thus leaving us with just the riddle which is wrapped in that single line verse in the Tiruvalangadu Copper plates.

And all that we have today, is that probable pen picture of the Goddess as etched by Muthusvami Dikshitar (in his kriti ‘mahishAsuramardanI’ in the archaic raga Narayani) which we have so surmised. And not to forget that granite bas relief of that Nishumbhasudani in that corner room in the second floor of the Philadelphia Museum’s South Asian Art section. And so, if one gets to see her at the Museum or were to get the opportunity to hear the composition ‘mahishAsuramadhini’ in Narayani of Dikshitar , they should pause for a moment to offer obeisance to that legendary Nishumbasudani of Tanjore and admire at the Narayani resurrected by Muthusvami Dikshitar for us. And perhaps one would also hark back and wonder what could have happened that fateful day in the year 969 AD when the young and valiant Chola Crown Prince died unnaturally.

Bibliography:

- K A Nilakanta Sastri (1955) – The Colas (English)– University of Madras

- Kudavoyil Balasubramanian ( NA) – Udayarkudi Inscriptions – A Relook/Review- ‘udayArkudi kalvettu – Oru mIL pArvai’ (Tamil) – Varalaaru.com article in 3 parts in Issue Nos 24, 25 and 27

- Subbarama Dikshitar(1904) – Sangita Sampradaya Pradarshini – Republished in Tamil by Madras Music Academy ( 1977) Part IV pp 843-846

- Dr Hema Ramanathan (2004) – ‘Ragalakshana Sangraha’- Collection of Raga Descriptions pp 275-278 and 963-974

Foot Notes:

- Much of the material for this blog is sourced from the references from Prof Nilakanta Sastri’s seminal work, ‘The Cholas”. The works of Prof Nilakanta Sastri and that of Sadasiva Pandarathar, together with the monographs and works of latter day archeologists, historians and epigraphists such as Dr Nagaswami, N S Sethuraman, Kudavoyil Balasubramanian and Dr G Sankaranarayanan can be profitably read to draw useful inferences as to the timelines of the medieval Chola Kings, events during their reign and their accomplishments. It has to be said that the epigraphical records are prone to different interpretations by different epigraphists. In so far as the subject matter of this blog post is concerned all these historical personalities, dates and events pertaining to the medieval Cholas are grounded in the following set of sources:

Epigraphy – Specifically the Udayarkudi inscriptions together with inscriptions cited by the experts/historians cited above whose works I have read and relied upon.

Copper plates (‘cheppu aedugal’ in Tamil) – The records of the Chola Kings which were found later in the 20th century known to us today as Tiruvalangadu Copper plates pertaining to this specific period. The other two sources being the Anaimangalam copper plates (Leiden copper plates) and the Anbil copper plates have nothing to contribute directly to the subject matter of this blog post.

Off course reliance is primarily placed on Prof Nilakanta Sastri’s work and he in turn uses third party sources as well in his reconstruction of the history of the medieval Cholas.

- The first section of the Thiruvalangadu Copper plates contains a set of 137 verses in Sanskrit, written by one Narayana during the reign of Rajendra Cola and narrates the lineage and history in brief of the Imperial Cholas. Without just relying on one set of records, I personally find that the logic employed by modern epigraphists/historians like Kudavayil Balasubramanian and Dr G Sankaranarayanan by which they triangulate the dates and events with other evidences including those of rock and temple inscriptions, very persuasive. It must be remembered that the copper plate records serve as epigraphs recording history casting the reigning King in the most favourable light. The Tiruvalangadu Copper plates were created during the reign of Rajendra Cola, the Anaimangalam copper plates (known as Leyden plates as they are presently housed in Leyden Museum in Netherlands) were created during the reign of Raja Raja Chola (985 -1014 AD) and the Anbil Copper plates date back to the reign of Parantaka Sundara Chola.

- Author Kalki Krishnamurthi cogently and convincingly opines through his work that Crown Prince Aditya Karikala was probably named after in memory of the legendary King Karikala of the Old Chola lineage and Prince Rajaditya the short lived yet legendary grand uncle of his and a grandson of Vijayalaya, who was felled by deceit in battle at Takkolam when he was fighting atop his elephant and therefore eulogised in epigraphs as ‘Anai mEl thunjiya tEvar’.

- Though this medieval Nishumbhasudani Temple no longer exists, a number of other Durga/Kali temples in Tanjore exists today probably attesting to the popularity of this cult worship in this area. Currently the well-known ones are the Vadabadra Kali Amman Temple and the other being the Ugra Kaliamman Temple, which perhaps proclaim themselves to be the original one constructed by Vijayalaya in 10th Century AD

- For us only verses 68 & 69 of the Thiruvalangadu plates and the said Udayarkudi inscriptions tell us this unsaid & long forgotten mysterious death of the Chola Prince. The assassination of Prince Aditya Karikala and the unsolved mystery of who actually did or could have done the deed, spawned not just various theories of conspiracy by subsequent historians but also a number of literary works which went on to capture the imagination of 20th century readers. These were part true-part fiction works, the foremost amongst them being Kalki Krishnamurthi’s ‘Ponniyin Selvan’, Balakumaran’s “Kadigai’ and ‘Udayar’, Kovi Manisekaran’s ‘Aditya karikAlan kOlai” & ‘T A Narasimhan’s Sangadhara’. While Kalki Krishnamurti in his ‘Ponniyin Selvan’ created a host of real & imaginary characters in his plot and left the identity of the real killer open in suspense, Sri Balakumaran in his Kadigai, made Madurantaka Uttama Chola as the instigator-in-chief, even while in one other novel, Raja Raja Chola and Princess Kundavai, the siblings of Crown Prince Aditya Karikala were made as the mastermind for the royal assassination. Amongst the historians, the earliest being Prof T A Nilakanta Sastri based on epigraphical evidence argued that given the verses 68 & 69 of the Tiruvalangadu Copper plates, Madurantaka Uttama must have had a hand in the death of Crown Prince Aditya Karikala, given that post Aditya’s assassination he had evinced interest to become the King & he was made one by Arulmozhi Verman who gave up his claim. In other words, Prof Nilakanta Sastri did not assign importance to the Pandyan conspiracy angle and the possibility of the three assassinators, named in the Udayarkudi inscription acting on their own to murder Aditya Karikala. Archeologist Kudavoyil Balasubramanian in his analysis of the Udayarkudi Inscription, gives an excellent summary of the take of different historians and proceeds to argue that Prof Nilakanta Sastri was mistaken in his assessment. Sri Balasubramanian basing his case on multiple sources including the much later unearthed Chola copper plates from Rajendra’s reign from near Esalam near Villupuram during the 1980’s and reading the Udayarkudi inscriptions in context, concludes that Aditya Karikala’s assassination was only the handiwork of the three perpetrators named in the said Udyarkudi inscription namely Soman, Ravidasan and Parameswaran in revenge for the killing of their Pandyan master King Veerpandya by Aditya Karikala earlier and Uttama Chola had no role to play in the said tragedy, based on the reading of the available evidence. See Epilogue.

- Mysore Vasudevachar’s grandson in his publication ‘Sangita Samaya’ recounts a humorous incident that happened in the context of this Dikshitar composition ‘mahishAsura mardhini’ in Narayani.

“ …………………….After the Navaratri festival, the float festival would begin on the Chamundi hills and the Maharaja had directed that vidwans, Bidaram Krishnappa and Vasudevachar, should jointly sing Dikshitar’s “Mahishasura Mardhini” in Narayani raga. Neither of them knew this song; in no time they learnt the Pallavi and violinist Venkataramanayya the tune of the Pallavi. They managed to render it when the float carrying the royal party was there and stopped when the float moved away. Venkataramanayya was happy that they had successfully hoodwinked the royalty. Imagine their predicament when they were asked to render the Anupallavi and the Charanam also.” https://www.thehindu.com/thehindu/2001/04/17/stories/1317017d.htm

7. The composition in the raga Gaula attributed to Muthusvami Dikshitar can be heard rendered in the following URL’s. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=02aBFW62wjM and https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QMgl-hjeuLU

EPILOGUE:

Much as one would like to write an epilogue regarding some archaeological find regarding the discovery of that original icon of ‘nishumbhasUdani’ of that Tanjore temple. Alas there isn’t one as yet. That apart one other inspiration for this blog post, for me has been the enduring mystery of the death of Aditya Karikala, the Chola Crown Prince in 969 AD, fuelled by several re-readings of Ponniyin Selvan and the other fictions and also the historical works of Prof Nilakanta Sastri and Sri Sadasiva Pandarathar. Kalki Krishnamurthi in his part real/part fiction novel had created a number of characters in his narrative such as Nandhini, the cunning and seductive Junior Rani of Pazhuvoor, her consort the Periya Pazhuvettarayar (a Chola feudatory and the Chancellor of the Chola Exchequer in the story) alongside the real life ones being Vandhiya Tevar ( later Royal Consort of Princess Kundavai), Ravidasan and Soman and made them all come together with Aditya Karikala in that dark underground chamber in the Kadamboor Palace that fateful night in 969 AD even as he left the identity of the killer whose fateful act took Aditya’s life open. However he ensured that the needle of suspicion did not point to Uttama Chola ( there being two individuals one, an original and the other a pretender, again fictional). Sri Balakumaran on the contrary in Kadigai makes the Brahmin identity of the perpetrators as a key and spins his tale making Uttama Chola as well as the Queen Mother Sembian Madevi a party to the conspiracy and packing the proceedings with considerable action in Pandya and Kerala country. I should confess that I have not had the appetite to read the other novels based on this plot, but nevertheless got inquisitive to know the epigraphical basis for the storyline/actual event and also the true state of affairs that the historical evidence was pointing to. Finally, I got to read the unequivocal and expert assessment of available evidence by the respected Archaeologist/Historian Kudavoyil Balasubramanian together with the monograph on the Chola Era finds in Esalam in Villupuram, made by Dr Nagaswami in 1987, which proved to be the icing on the cake for me as these two monographs clinically summarizes the position based on available hard facts and likely clears the air as to the mystery who likely killed Aditya Karikala, a vexed question which has been lacking a formal closure all these years. The Tamil original version of Mr Balasubramanian’s monograph on the subject is here. I have taken the liberty of translating it in English which can be read here. A consolidated view of all these, deserves a separate blog post.