INTRODUCTION:

‘Cittasvaras’ or more conventionally ‘muktayisvaras’ are svara appendages/solfeggio passages seen in darus, varnas, kritis, ragamalikas and svarajatis. In focus for this short blog post, will be usage of this compositional anga/feature as it applies to kritis and more specifically Muttusvami Dikshitar’s as documented in the Sangita Sampradaya Pradarshini (SSP). In the SSP Subbarama Dikshitar utilizes the terms svarams, muktayi svarams, svara jathi and anuloma-viloma svaram in the SSP and for this article the term ‘cittasvaram’ shall be used to encompass all these in scope for the discussion for the sake of uniformity and convenience. (See Footnote 1)

CITTASVARAS – KEY FEATURES:

- A cittasvara conjoins two parts of the composition and typically span two or four avartas of the tala cycle to which the composition has been set.

- Almost naturally the cittasvara feature is mandatory for varnas, svarajathis and darus while it is only optional for kritis. In the case of ragamalikas it enables the composition to traverse/transition from one raga to another seamlessly.

- In varnas (both tana and cauka), darus and svarajathis this svara section is sung as the anu-pallavi loops back to the pallavi section. In the case of kritis and ragamalikas the cittasvara section is rendered upon the conclusion of the anupallavi and carana section.

- These solfeggio passages are called as ettugada svaras in the case of varnas when appended in sequence to the carana portion of the composition. For varnas one can notice that a minimum of 3 ettugada svara sections exists for a given composition.

- Cittasvaras can optionally have corresponding sahitya section.

- In the case of cauka varnas, svarajathis and darus, these solfeggio passages apart from sahitya may also have sollukattu/jatis to be rendered.

- Cittasvaras in the cases of certain compositions can also get added subsequently by individuals other than the original composer of the composition. Same is the case of the associated sahitya/jathis composed for these solfeggio passages.

Lets first look at what could be the role that this anga/part of a composition plays and the history if any associated with this feature in the case of kritis. (See Footnote 2)

CITTASVARAS – HISTORY:

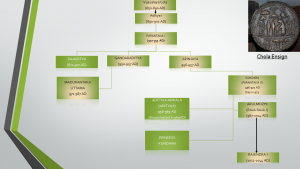

By the turn of the 17th/18th century as the prabandhas gave way to varnas, svarajathis, kritis and other compositional forms, in all probability the cittasvara feature got first used in varnas and svarajathis as a mandatory component/anga of the composition. The evolution of the modern day kriti format has been a subject matter of considerable speculation. However one can say that in the run up to the Trinity, composers of the like of King Shahaji, King Tulaja, Melattur Veerbadrayya, Kavi Matrubhutayya & others had laid the foundations for the template which was improvised and used by Tyagaraja, Dikshitar and Syama Sastri. And it was perhaps during their time that kritis came to be composed in profusion. In the case of cittasvara becoming or being made as a component or anga of a kriti, according to Dr Sita, the earliest recorded kriti having a cittasvara section is ‘Neemathi Callaga’ of Kavi Matrubhutayya. Again she notes that cittasvara passages are available for padas composed by Tulaja, which are more in the nature of kritis rather than those what we call as padas today .One doesn’t know with certainty if Tulaja or Matrubhutayya were indeed the first ones to do so but the corpus of evidence available to us bears out the finding of Dr Sita.

ROLE OF CITTASVARA IN A KRITI:

Per se it is very difficult to nail down the precise reason or reasons for the existence/usage of cittasvara in a kriti type of composition. At a minimum it may be at best thought of as a compositional device to extend the musical idea of a kriti by additionally augmenting the sahitya with svara passages which should at the minimum meet two important requirements:

- The cittasvara section must seamlessly blend with the overall composition structurally and enable the performer to move fluidly from the previous compositional section/anga i.e the anupallavi or carana to the Pallavi.

- It must be aligned to the raga lakshana as delineated in the other parts of the composition.

Again for this blog post I seek to restrict myself to the way Muthusvami Dikshitar has dealt with this anga or compositional part in his creations as documented in the Sangita Sampradaya Pradarshini (SSP). Apart from the kritis, cittasvaras/muktayi svaras are also seen in the 2 ragamalikas and the Todi varna and the Sriranjani daru attributed to him and found in the SSP and its anubandha. That apart Muthusvami Dikshitar has also composed one of the ettugada svara passages (along with Syama Sastri and Cinnasvami Dikshitar) for the Sriranjani varna left unfinished by Ramasvami Dikshitar (vide Subbarama Dikshitar’s footnote in the SSP).

CITTASVARAS IN MUTHUSVAMI DIKSHITAR’s COMPOSITIONS & DISCOGRAPHY:

In this section we will cover the way in which Dikshitar has utilized the cittasvara feature in his compositions along with the associated discography. The SSP has documented a good number of compositions of Dikshitar with cittasvaras. In fact Subbarama Dikshitar has utilized the term ‘muktayi svaras’ to synonymously refer to cittasvaras. Almost invariably in terms of distribution, once can notice that a good majority of all the so called samashti carana kritis documented in the SSP have the cittasvara section appended to them. Despite being recorded in the SSP, the cittasvaras for many Dikshitar’s compositions are almost never rendered or heard in the concert circuit.

The study of the SSP documentation gives us a few pointers as to why this compositional anga has been used by Dikshitar. We can state with confidence that Dikshitar has not perfunctorily used the cittasvara feature for the sake of using it but he has applied it thoughtfully & uniquely to fulfill a compositional objective. This line of thought can be articulated by way of illustrated examples as under:

Illustration 1:

In the case of compositions in the asampurna mela raaganga ragas employing vivadhi notes, one can notice that Dikshitar has structured the composition in a very concise manner just with the Pallavi and the anupallavi alone (the so called samashti carana format) perhaps given the limited scope for elaborating these scales which would have been new at that point in time. Examples include the compositions in the vivadhi raagangas like Jyoti, Ragachudamani, Santanamanjari. Kuntalam and Rasamanjari.

These short compositions (in the samashti carana format) themselves typically end in four or eight cycles of tala. In these cases one can note that Dikshitar melodically extends the composition by utilizing the cittasvara feature to encapsulate and additionally clarify the melodic definition of these asampurna melas which at that point were just theoretical creations of Muddu Venkatamakhin. In fact many of these ragas are eka kriti ones with these solitaires created by Dikshitar standing as the sole repository/example of their raga lakshanas. Muddu Venkatamakhin’s lakshana shlokas for these ragas do not define any arohana/avarohana krama and those one finds in the SSP are as given by Subbarama Dikshitar on the strength of the compositions – primarily the Dikshitar compositions.

It is possible to divine Dikshitar’s objective in using cittasvaras for these compositions. In the cases of these asampurna vivadi raagangas, a full blown carana section could possibly be an overkill making the composition unwieldy and monotonous due to repetitive raga murccana phrasings. A short and pithy cittasvara section would have fitted the bill and hence Dikshitar should have in all probability utilized the feature to achieve his compositional objective of providing flesh and blood to these then still born ragas.

We look at the presentation of the cittasvaras for two raaganga melas, one each from the suddha madhyama and prati madhyama raagangas namely Ragacudamani (32nd mela in the asampurna mela scheme) and Rasamanjari (72nd mela).

First Sangita Kala Acharya Smt Seetha Rajan renders the cittasvara section of the Dikshitar composition ‘Svetaganapatim’ as found documented in the SSP.

<<Vidushi Seetha Rajan presents ‘Svetaganapatim’>>

Attention is invited to the raga lakshana features that Dikshitar additionally covers in the cittasvara section which perhaps he wasn’t able to completely cover in the pallavi and anupallavi sections.

We move on to the Rasamanjari kriti ‘Shringara Rasamanjari’. This illustration is best explained by this kriti which is in a raga which has vivadhi svara combination both in the purvanga and uttaranga and all the svaras save for S and P being teevra svaras. Vidushi Seetha Rajan explains how Dikshitar has structured Rasamanjari with a series of murccanas as under:

<<Vidushi Seetha Rajan explains the conception of Rasamanjari by Dikshitar>>

<<Vidushi Seetha Rajan follows up by singing the composition together with the cittasvara as found verbatim in the SSP>>

As one can see the arohana prayogas as SRGS SPM PNDNs and avarohana prayogas as sNDNP PMP RGS is how Subbarama Dikshitar presents Rasamanjari on the authority of Dikshitar’s composition. As one can notice it is these murccanas with the pancama svara as the pivot that the cittasvara section is structured very clearly in continuation with the sahitya. (See Foot note 4)

Another collateral objective that one can surmise is that Dikshitar introduced these cittasvaras purposefully to ensure that his musical idea as to that ragaanga was codified in svara form in the cittasvara section so that the lakshana enshrined therein would form the beacon light for the future even if the notation of the sahitya section were to be lost / changed. This needs to be viewed with the fact that in those days notations were non-existent and sahitya of the kritis were alone recorded in palm leaf manuscripts without the corresponding dhathu. Given such a scenario, one can surely expect the raga lakshana to be mutilated or changed beyond redemption. Apart from embedding the raga name in the composition, Dikshitar perhaps took this additional step of adding the cittasvaras to preserve in entirety, the integrity of the composition & raga lakshana so that they too will get recorded as svaras themselves along with the sahitya.

In fact one shudders to think what would have been the case if we did not have the SSP (which bears the notation of the composition) and the cittasvaras as well! Notwithstanding the documentation in the SSP, it’s indeed sad that we do have versions of Dikshitar’s compositions which have been normalized to the krama sampurna equivalent scales and so rendered.

Illustration 2:

Illustration 2 is a special case of Illustration 1 in that the Dikshitar has employed the cittasvara feature to embody the collective montage of an older/obscure/rare raga as visualized by him in a succinct manner. Compositions in ragas like Balahamsa or Andhali are classic examples. These ragas date back prior to the trinity themselves and have been documented by Venkatamakhi, Muddu Venkatamakhi, Shahaji and/or Tulaja.

In this section presented first is Andhali kriti ‘Brihannayaki Varadayaki’ rendered by Sangita Kala Acharya Kalpagam Svaminathan.

Attention is invited to the unique usage of the nishada svara in the cittasavara section which is not to be seen elsewhere in the composition. Also the emphasis that needs to be given to the recurrent leitmotif of Andhali namely the murccana RGMR is highlighted by Dikshitar in this cittasvara section.

Presented next is the rendering of the cittasvara section of the Guruguha vibakthi kriti ‘Guruguhadanyam najaneham’.

<< XXX renders the cittasvara section of ‘Guruguhadanyam’>>

Illustration 3:

Illustration 3 is again another special case of Illustration 1 in that the Dikshitar has employed the cittasvara feature not just to feature the raga but also add a rhythmic alankara/ornamentation to the section. A very appropriate example is the cittasvara appended to the Guruguha Vibakti kriti in the raga Sama, ‘guruguhAya bhaktAnugrahAya’ in Adi tAla. Presented below is an excerpt from a lecture demonstration of VDr T S Satyavati where she shows how Dikshitar in the cittasvara section shows an apparently different gait to the rhythm.

<< dr T S Satyavati renders the cittasvara section of ‘Guruguhaya’>>

Illustration 4:

In certain other cases the cittasvara section is featured by Dikshitar to present a musicological feature which is unique to the raga, which has long gone into oblivion. Examples include the cittasvara section featuring graha svara usage in the Revagupti composition ‘Sadavinata sadare’ and in the Kannadabangala composition ‘Renuka devi samrakshitoham’.

In the clipping below the cittasvara for the Revagupti composition ‘sadAvinata sAdarE’ is presented. It is first rendered with the svaras being rendered as is in their respective tonal positions. Next the graha svaras are rendered as if they are the sahitya for the same tonal positions. Interested readers may refer to Dr N Ramanathan’s monograph on the subject. (See Foot note 3)

<< Dr Abhiramasundari renders the grahasvara portion of ‘Sadavinata sadare’>>

Illustration 4:

In this illustration we highlight two important usages of cittasvaras made by Dikshitar to emphasize a feature associated with the subject matter of the composition:

a. Anuloma-Viloma cittasvara:

This very creative & interesting usage by Dikshitar of the anuloma- viloma (palindrome) feature is evident in the cittasvara section of the Kalyani navavarna “Kamalambam bhajare’. For this composition it’s not without reason that Dikshitar has used the anuloma-viloma feature (i.e the cittasvara rendering would be the same both forwards & backwards). The Kalyani composition is for the second avarana or chakra. For every chakra, in Srividya there is a pUja vidhAnam or protocol, i.e. there in a pre-ordained sequence in performing the puja for a particular chakra and the direction/sequence in which it is to be done is either clockwise ‘or’ anticlockwise. For the second chakra however (to which this Kalyani composition pertains) the protocol/sequence is that it can be ‘both’ clockwise and anticlockwise and it is an exception. No wonder this is musically signified by Dikshitar by having an anuloma-viloma cittasvara i.e. the cittasvaras, whichever way rendered forward or clockwise/backward or anticlockwise, is the same. It’s worth noting here that the Kalyani navavarna is the only composition in the entire set to feature a cittasvara section.

<<Vidusi Gayathri Girish renders the anuloma-viloma cittasvara of the Kalyani Navavarna>>

b. Cittasvaras with sollukattus/jatis:

The other interesting usage of cittasvara is the case of the one appended to the pancabhuta kshetra kriti “Anandanatana prakasam” in Kedaram. The cittasvara here features jatis or sollukattus interspersed with svara syllables to highlight the rhythmic gait of Lord Nataraja as he is the Lord of dance and is the one eulogized in the composition.

<< Vidushi Rama Ravi renders the composite cittasvara passage of ‘Ananda Natana prakasam’>>

It’s worth highlighting here that a similar such cittasvara section with sollukattus/jatis interspersed with svara syllables is available for the Gaula composition ‘Sri Mahaganapathiravatumam’. However the text of that cittasvara is not seen in the SSP making one wonder if it was perhaps a latter day addition. According to Vidvan T S Partahasarathy this is a creation of …………..

Illustration 5 :

- Yet another odd usage of the cittasvara by Dikshitar is in the case of the Gauri raga composition ‘Sri Meenakshi Gauri’ where two different svara sets are appended to the composition, one as muktayi svara for the anupallavi and another as svaram for the carana portion of the composition. The said terms ‘muktayi svara’ and ‘svaram’ are found as the labels for these sections in the SSP.

<<Dr Abhiramasundari renders the Gauri kriti ‘Sri Meenakshi Gauri’ as per the notation found in the SSP>>

It’s clearly a puzzle why such a feature was adopted by Dikshitar in this composition and what was the compositional objective he was trying to fulfill. Wish one knew the answer.

- The cittasvara section of the Revagupti composition mentioned aforesaid, which is composed as graha svaras is also structured in the anuloma-viloma style as well. It may well be possible that Dikshitar was blending two archaic/novel composing constructs in this cittasvara structuring and thus exemplifies his composing virtuosity.

CONCLUSION:

The history of how cittasvaras came about is a very elaborate and intensive area of study. The objective of this post has been just to look at how this anga or ornamentation that can be done to a composition has probably been utilized by Muthusvami Dikshitar. The feature must have likely first made its debut in the varnas followed by ragamalikas and then must have come to kritis. Melattur Virabadrayya, the preceptor of Ramasvami Dikshitar was a past master in creating ragamalikas and the scions of the Dikshitar family including Ramasvami Dikshitar, Muthusvami Dikshitar and Subbarama Dikshitar have all gone on to embellish their ragamalikas with pithy cittasvaras capturing the very essence of the raga in a short avarta of a tala.

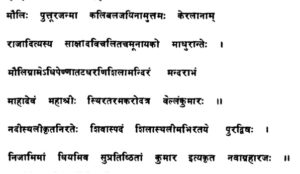

I conclude this post with one of the older ragamalikas available to us today, a compostion of Ramasvami Dikshitar composed in a King of Tanjore, Raja Amarasimha, which was featured in an earlier blog post. One can not only admire the way Ramasvami Dikshitar has woven the ragas into the text but also the way in which he as captured the essence of the ragas in their respective short cittasvara sections.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

I thank Vidushis Gayathri Girish & Dr A Abhiramasundari for providing the clips and permitting me to share the same in the public domain. The other clippings are/were already in the public domain and are shared

Foot Notes:

- It needs to be placed on record that the foregoing is a purely personal perception or set of insights derived exclusively out of the understanding (limited or otherwise) gained by studying Muthusvami Dikshitar’s compositions as found in the SSP and other associated materials including recordings and lecture demonstrations or research works as found in the discography/references section of this blog post.

- Readers are advised to refer to pages 199-219 of Prof S R Janakiraman’s musicological text ‘Essentials of Musicology of South Indian Music’ for some perspectives on the different angas of kritis including cittasvaras.

- Readers may refer to Dr N Ramanathan’s monograph on Grahasvaras- Journal of the Music Academy Vol LXIX (1998)-pages 15-58 “Grahasvara passages in Dikshitar Kritis”. The same is also available at : http://www.musicresearch.in/contents.php?sortfield=1

- The 72nd raaganga kriti of Dikshitar in the raga Rasamanjari is indeed a sort of pinnacle of Dikshitar’s compositional excellence. Authorities/Accounts have it that on the request of the Tanjore Quartet, Dikshitar composed in all the 72 raagangas with most of the compositions being dedicated to Goddess Kamakshi at Tanjore. In this Rasamanjari composition Dikshitar makes the reference to the 72 raaganga model, the grand patriarchs of music/dance namely Bharatha and Matanga and finally the rasika or the person who revels or savors music/art. The inclusion of the word ‘rasika’ in this composition in particular makes one wonder if by accident or design , Dikshitar was implying his knowledge of the heptatonic equivalent ‘Rasikapriya’. That apart Dikshitar extols Kamakshi (and perhaps the raga as well ) as ‘mangala dayini’ ( bestower of prosperity) probably for the benefit of those laboring under the impression that rendering such ragas would invite dosha !

Safe Harbor Statement: The clipping and media material used in this blog post have been exclusively utilized for educational / understanding /research purpose and cannot be commercially exploited or dealt with. The intellectual property rights of the performers and copyright owners are fully acknowledged and recognized.

Short Notes: Cittasvaras or Muktayisvaras:

‘Cittasvaras’ or more conventionally ‘muktayisvaras’ are svara appendages/solfeggio passages seen in darus, varnas, kritis, ragamalikas and svarajatis. In focus for this short blog post, will be usage of this compositional anga/feature as it applies to kritis and more specifically Muttusvami Dikshitar’s. For the sake of uniformity and convenience the term ‘cittasvara’ shall be used in the rest of this short blog post. (See Footnote 1)

Cittasvaras -Key Features:

1.A cittasvara conjoins two parts of the composition and typically span two or four avartas of the tala cycle to which the composition has been set.

2.Almost naturally the cittasvara feature is mandatory for varnas, svarajathis and darus while it is only optional for kritis. In the case of ragamalikas it enables the composition to traverse/transition from one raga to another seamlessly.

3.In varnas (both tana and cauka), darus and svarajathis this svara section is sung as the anu-pallavi loops back to the pallavi section. In the case of kritis and ragamalikas the cittasvara section is rendered upon the conclusion of the anupallavi and carana section.

4.These solfeggio passages are called as ettugada svaras in the case of varnas when appended in sequence to the carana portion of the composition. For varnas one can notice that a minimum of 3 ettugada svara sections exists for a given composition.

5.Cittasvaras may or may not have corresponding sahitya section.

6.In the case of cauka varnas, svarajathis and darus, these solfeggio passages apart from sahitya may also have jatis to be rendered.

7.Cittasvaras in the cases of certain compositions can also get added subsequently by individuals other than the original composer of the composition. Same is the case of the associated sahitya/jathis composed for these solfeggio passages.

Lets first look at what could be the role that this anga/part of a composition plays and the history if any associated with this feature in the case of kritis. (See foot note 2)

Cittasvaras -History & Role:

By the turn of the 17th/18th century as the prabandhas gave way to varnas, svarajathis, kritis and other compositional forms, in all probability the cittasvara feature got first used in varnas and svarajathis as a mandatory component/anga of the composition. The evolution of the modern day kriti format has been a subject matter of considerable speculation. However one can say that in the run up to the Trinity, composers of the like of King Shahaji, King Tulaja, Melattur Veerbadrayya, Kavi Matrubhutayya & others had laid the foundations for the template which was improvised and used by Tyagaraja, Dikshitar and Syama Sastri. And it was perhaps during their time that kritis came to be composed in profusion. In the case of cittasvara becoming or being made as a component or anga of a kriti, according to Dr Sita, the earliest recorded kriti having a cittasvara section is ‘Neemathi Callaga’ of Kavi Matrubhutayya. Again she notes that cittasvara passages are available for padas composed by Tulaja, which are more in the nature of kritis rather than those what we call as padas today .One doesn’t know with certainty if Tulaja or Matrubhutayya were indeed the first ones to do so but the corpus of evidence available to us bears out the finding of Dr Sita.

Role of a Cittasvara in a kriti:

Per se it is very difficult to nail down the precise reason or reasons for the existence/usage of cittasvara in a kriti type of composition. At a minimum it may be at best thought of as a compositional device to extend the musical idea of a kriti by additionally augmenting the sahitya with svara passages which should at the minimum meet two important requirements:

1.The cittasvara section must seamlessly blend with the overall composition structurally and enable the performer to move fluidly from the previous compositional section/anga i.e the anupallavi or carana to the Pallavi.

2.It must be aligned to the raga lakshana as delineated in the other parts of the composition.

Again for this blog post I seek to restrict myself to the way Muthusvami Dikshitar has dealt with this anga or compositional part in his creations as documented in the Sangita Sampradaya Pradarshini (SSP).

Cittasvaras in Muthusvami Dikshitar’s Compositions & Discography:

In this section we will cover the way in which Dikshitar has utilized the cittasvara feature along with the associated discography.

The SSP has documented a good number of compositions of Dikshitar with cittasvaras. In fact Subbarama Dikshitar has utilized the term ‘muktayi svaras’ to synonymously refer to cittasvaras. Almost invariably in terms of distribution, once can notice that a good majority of all the so called samashti carana kritis documented in the SSP have the cittasvara section appended to them. Despite being recorded in the SSP, the cittasvaras for many Dikshitar’s compositions are almost never rendered or heard in the concert circuit.

It is my understanding that Dikshitar has not perfunctorily used the cittasvara feature for the sake of using it but he has applied it thoughtfully & uniquely to fulfill a compositional objective. This line of thought can be articulated by way of illustrated examples as under:

Illustration 1:

Ragaanga Ragas: In the case of compositions in quite a few of the asampurna mela raaganga ragas employing vivadhi notes, one can notice that Dikshitar has structured the composition in a very concise manner just with the Pallavi and the anupallavi alone (the so called samashti carana format) perhaps given the limited scope for elaborating these scales which would have been new at that point in time. Examples include the compositions in the vivadhi raagangas like Jyoti, Ragachudamani, Santanamanjari. Kuntalam and Rasamanjari.

These short compositions (in the samashti carana format) themselves typically end in four or eight cycles of tala. In these cases one can note that Dikshitar melodically extends the composition by utilizing the cittasvara feature to encapsulate and additionally clarify the melodic definition of these asampurna melas which at that point were just theoretical creations of Muddu Venkatamakhin. In fact many of these ragas are eka kriti ones with these solitaires created by Dikshitar standing as the sole repository/example of their raga lakshanas. Muddu Venkatamakhin’s lakshana shlokas for these ragas do not define any arohana/avarohana krama and those one finds in the SSP are as given by Subbarama Dikshitar on the strength of the compositions – primarily the Dikshitar compositions and the tanas/gitas of the older order.

It is possible to divine Dikshitar’s objective in using cittasvaras for these compositions. In the cases of these asampurna vivadi raagangas, a full blown carana section could possibly be an overkill making the composition unwieldy and monotonous due to repetitive raga murccana phrasings. A short cittasvara section would have fitted the bill and hence Dikshitar should have in all probability utilized the cittasvara feature to achieve his compositional objective of providing flesh and blood to these then still born ragas.

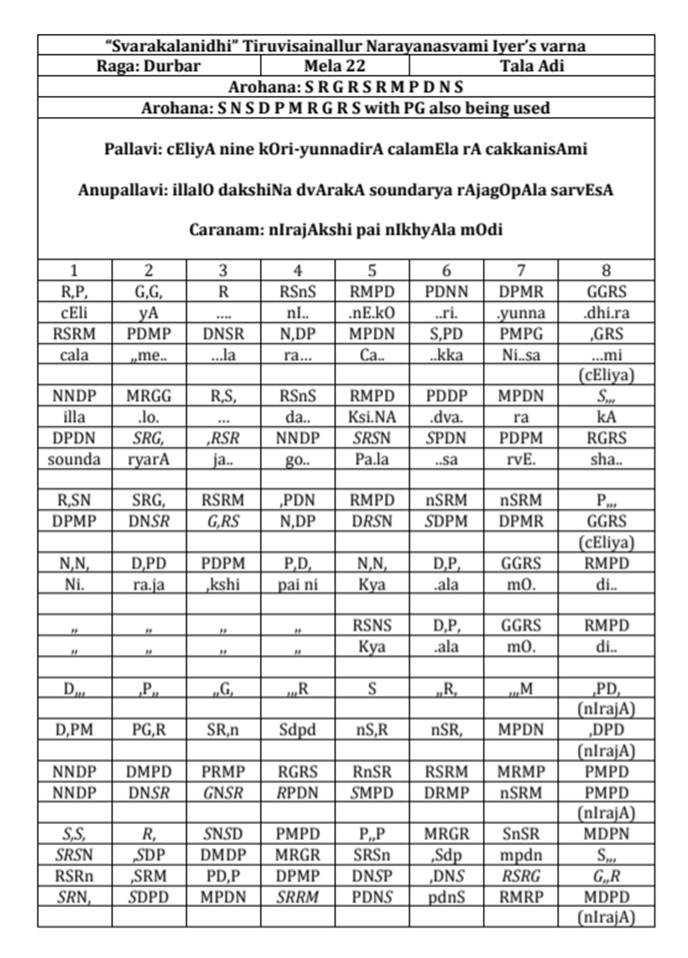

We look at the presentation of the cittasvaras for two raaganga melas, one each from the suddha madhyama and prati madhyama raagangas namely Ragacudamani (32nd mela in the asampurna mela scheme) and Rasamanjari (72nd mela).

First Sangita Kala Acharya renders the cittasvara section of the Dikshitar composition ‘Svetaganapatim’ as found documented in the SSP.

<<Vidushi Seetha Rajan presents ‘Svetaganapatim’>>

Attention is invited to the raga lakshana features that Dikshitar additionally covers in the cittasvara section which perhaps he wasn’t able to completely cover in the pallavi and anupallavi sections.

We move on to the Rasamanjari kriti ‘Shringara Rasamanjari’.

This illustration is best explained by this kriti which is in a raga which has vivadhi svara combinations both in the purvanga and uttaranga and all the svaras save for S and P being teevra svaras. Vidushi Seetha Rajan explains how Dikshitar has structured Rasamanjari with a series of murrcanas as under:

<<Vidushi Seetha Rajan explains the conception of Rasamanjari by Dikshitar>>

<<Vidushi Seetha Rajan follows up by singing the composition together with the cittasvara as found verbatim in the SSP>>

As one can see the arohana prayogas as SRGS SPM PNDNs and avarohana prayogas as sNDNP PMP RGS is how Subbarama Dikshitar presents Rasamanjari on the authority of Dikshitar’s composition. As one can notice it is these murccanas with the pancama svara as the pivot that the cittasvara section is structured very clearly in continuation with the sahitya. (See Foot note 4)

At this juncture one can indeed surmise that Dikshitar introduced these cittasvaras purposefully to ensure that his musical idea as to that ragaanga was codified in svara form in the cittasvara section so that the lakshana enshrined therein would form the beacon light for the future even if the notation of the sahitya section were to be lost / changed. This needs to be viewed with the fact that in those days notations were nonexistent and sahitya of the kritis were alone recorded in palm leaf manuscripts without the corresponding dhathu. Given such a scenario, one can surely expect the raga lakshana to be mutilated or changed beyond redemption. Apart from embedding the raga name in the composition, Dikshitar perhaps took this additional step of adding the cittasvaras to preserve in entirety, the integrity of the composition & raga lakshana so that they too will get recorded as svaras themselves along with the sahitya.

In fact one shudders to think what would have been the case if we did not have the SSP (which bears the notation of the composition) and the cittasvaras as well! Notwithstanding the documentation in the SSP, it’s indeed sad that we do have versions of Dikshitar’s compositions which have been normalized to the krama sampurna equivalent scales and so rendered. Editions of the compositions in Nasamani and Vamsavati are examples of what Prof S R Janakiraman calls as acts of sacrilege!

Illustration 2:

Illustration 2 is a special case of Illustration 1 in that the Dikshitar has employed the cittasvara feature to embody the collective montage of an older/existing/popular raga itself as visualized by him in a succinct manner. Compositions in ragas like Balahamsa or Andhali are classic examples. These ragas date back prior to the trinity themselves and have been documented by Venkatamakhi, Muddu Venkatamakhi, Shahaji and/or Tulaja.

In this section presented first is Andhali kriti ‘Brihannayaki Varadayaki’ rendered by Sangita Kala Acharya Kalpagam Svaminathan.

Attention is invited to the unique usage of the nishada svara in the cittasavara section which is not to be seen elsewhere in the composition. Also the emphasis that needs to be given to the recurrent leitmotif of Andhali namely the murccana RGMR is highlighted by Dikshitar in this cittasvara section.

Presented next is the rendering of the cittasvara section of the Guruguha vibakthi kriti ‘Guruguhadanyam najaneham’

<< XXX renders the cittasvara section of ‘Guruguhadanyam’>>

Illustration 3:

In certain other cases the cittasvara section is featured by Dikshitar to present a musicological feature which is unique to the raga, which has long gone into oblivion. Examples include the cittasvara section featuring graha svara usage in the Revagupti composition ‘Sadavinata sadare’ and in the Kannadabangala composition ‘Renuka devi samrakshitoham’.

In the clipping below the cittasvara for the Revagupti composition ‘Sadavinata sadare’ is presented. It is first rendered with the svaras being rendered as is in their respective tonal positions. Next the graha svaras are rendered as if they are the sahitya for the same tonal positions. Interested readers may refer to Dr N Ramanathan’s monograph on the subject. (See Foot note 3)

<< Dr Abhiramasundari renders the grahasvara portion of ‘Sadavinata sadare’>>.

Illustration 4:

In this illustration we highlight two important usages of cittasvaras made by Dikshitar to emphasize a feature associated with the subject matter of the composition:

a.Anuloma-Viloma cittasvara:

This very creative & interesting usage by Dikshitar of the anuloma- viloma (palindrome) feature is evident in the cittasvara section of the Kalyani navavarna “Kamalambam bhajare’. For this composition it’s not without reason that Dikshitar has used the anuloma-viloma feature (i.e the cittasvara rendering would be the same both forwards & backwards). The Kalyani composition is for the second avarana or chakra. For every chakra, in Srividya there is a puja vidhanam or protocol, i.e. there in a pre-ordained sequence in performing the puja for a particular chakra and the direction/sequence in which it is to be done is either clockwise ‘or’ anticlockwise. For the second chakra however (to which this Kalyani composition pertains) the protocol/sequence is that it can be ‘both’ clockwise and anticlockwise and it is an exception. No wonder this is musically signified by Dikshitar by having an anuloma-viloma cittasvara i.e. the cittasvaras, whichever way rendered forward or clockwise/backward or anticlockwise, is the same. It’s worth noting here that the Kalyani navavarna is the only composition in the entire set to feature a cittasvara section.

b.Cittasvaras with sollukattus/jatis:

The other interesting usage of cittasvara is the case of the one appended to the Pancabhuta kshetra kriti “Anandanatana prakasam” in Kedaram. The cittasvara here features jatis or sollukattus interspersed with svara syllables to highlight the rhythmic gait of Lord Nataraja as he is the Lord of dance and is the one eulogized in the composition.

It’s worth highlighting here that a similar such cittasvara section with sollukattus/jatis interspersed with svara syllables is available for the Gaula composition ‘Sri Mahaganapathiravatumam’. However the text of that is not seen in the SSP making one wonder if it was perhaps a latter day addition.

Illustration 5

·Yet another odd usage of the cittasvara by Dikshitar is in the case of the Gauri raga composition ‘Sri Meenakshi Gauri’ where two different svara sets are appended to the composition, one as muktayi svara for the anupallavi and another as svaram for the carana portion of the composition. The said terms ‘muktayi svara’ and ‘svaram’ are found as the labels for these sections in the SSP.

<<Dr Abhiramasundari renders the Gauri kriti ‘Sri Meenakshi Gauri’ as per the notation found in the SSP>>

It’s clearly a puzzle why such a feature was adopted by Dikshitar in this composition and what was the compositional objective he was trying to fulfill. Wish one knew the answer.

·The cittasvara section of the Revagupti composition mentioned aforesaid, which is composed as graha svaras is also structured in the anuloma-viloma style as well. It may well be possible that Dikshitar was blending two archaic/novel composing constructs in this cittasvara structuring and thus exemplifies his composing virtuosity.

Foot Notes:

1.It needs to be placed on record that the foregoing is a purely personal perception or set of insights derived exclusively out of the understanding (limited or otherwise) gained by studying Muthusvami Dikshitar’s compositions as found in the SSP and other associated materials including recordings and lecture demonstrations or research works as found in the discography/references section of this blog post.

2.Readers are advised to refer to pages 199-219 of Prof S R Janakiraman’s musicological text ‘Essentials of Musicology of South Indian Music’ for some perspectives on the different angas of kritis including cittasvaras.

3.Readers are advised to refer to Dr N Ramanathan’s monograph on Grahasvaras- Journal of the Music Academy Vol LXIX (1998)-pages 15-58 “Grahasvara passages in Dikshitar Kritis”. The same is also available at : http://www.musicresearch.in/contents.php?sortfield=1

The 72nd raaganga kriti of Dikshitar in the raga Rasamanjari is a sort of pinnacle of Dikshitar’s compositional excellence. Authorities/Accounts have it that on the request of the Tanjore Quartet, Dikshitar composed in all the 72 raagangas with most of the compositions being dedicated to Goddess Kamakshi at Tanjore. In this Rasamanjari composition Dikshitar makes the reference to the 72 raaganga model, mentions the patriarchs of music/dance namely Bharatha and Matanga and finally the rasika or the person who revels or savors music/art.