( The featured image above of the Lord Brihadeesvara Temple at Tanjore is a photograph of Samuel Bourne, taken circa 1860 AD going with the caption” Great Pagoda and Stone Bull, Tanjore” – Image courtesy : The British Library)

Prologue:

In a previous blog post we had looked at the antecedents and the flavors of the raga Karnataka Kapi. Since then, I happened to encounter a rendering of the rare cauka varna “sarasAlanu” in the raga, composed by Ponnayya of the Tanjore Quartet, on YouTube. I had fleetingly referred to this particular composition in the aforesaid blog post. And therefore, in this blog post I propose the take the reader through this composition in detail and relish its beauty from multiple dimensions.

It is to be noted that the raga of sarasAlanu is always given as Kapi. In view of the different variants of the raga which exists in our world of music, in this blog post I am referring to the raga of the composition as Karnataka Kapi, which name came about to signify that it was an older form and not the later day versions.

Clones in our world of Music:

But before that I seek to present a few aspects of some of the timeless & great compositions which have been in vogue in our world of music. Subbarama Dikshitar in his works waxes eloquent about a varna in the raga Navaroz of Karvetinagar Govindasamayya and of a svarajati in Huseni by Melattur Virabhadrayya. Seemingly these compositions had captured popular imagination during those times so much so that a number of copies or look-alike compositions came to be composed, virtually with the same musical setting or mettu of these magna operas. The Navaroz varna is today virtually extinct. Melattur Virabhadrayya’s lilting Huseni svarajati which in its original form too is today extinct, spawned at least 3 clones “emAyalAdira”, emandayAnara” and “pAhimAm brihannayikE” with attributions to Patchimiriyam Adiyapayya, the Tanjore Quartet and Svati Tirunal. The version recreated by Adiyappaya being “Emandayanara” was salvaged and is found presented in the Sangita Sampradaya Pradarshini by Subbarama Dikshita. The Quartet version is documented in the “Tanjai Naalvar Manimalai” and the version attributed to Svati Tirunal can be found in Vidvan T K Govinda Rao’s compendia of his compositions.

In other words, if the melodic material /dhatu or mettu of a composition is so bewitching, it was never frowned upon as plagiarism if it were simply cloned with different set of lyrics, as if to validate the saying “Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery”. And being in public knowledge, no attribution was considered necessary, perhaps. It can also be seen that the dhatu of a couple of the compositions of Muthusvami Dikshita and Tyagaraja do match, for example “gananAyakam” and “srI mAnini”. Whether they are mutual copies or whether the two Trinitarians composed their version basing it on a then popular tune, of a now extinct piece, is not known. Rather the point to note is that it brings no discredit to Dikshita or Tyagaraja for having composed in a common tune for we know that their work was only in honor of the tune and its melodic appeal and their composing capabilities were beyond reproach.

Be that as it may, the subject matter varna “sarasAlanu” too has a similar such “clonal” history in that in its mettu or musical score, there exist one other composition being “sUmasAyaka” with attribution to Svati Tirunal. There are reasons to believe that the subject matter varna sarasAlanu is the likely original one while sUmasAyaka, which is more famous is the clone or copy subsequently created. We will examine this conjecture as well as the originality or uniqueness of this composition in this blog post.

“sarasAalanu Ipudu” in Karnataka Kapi of Thanjavur Ponnayya:

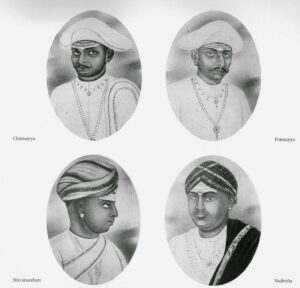

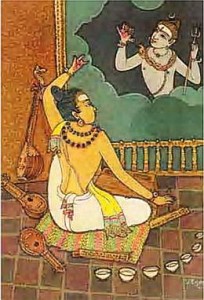

The aforesaid attribution of this composition, which is a cauka varna (more commonly called as a pada varna) to Ponnayya is on the authority of the “Thanjai Naalvar Manimaalai” published by Sangita Kalanidhi K P Sivanandam, a descendant of the Quartet. As we know the Tanjore Quartet of Chinnayya, Ponnayya, Sivanandam and Vadivelu were acknowledged disciples of Muthusvami DIkshita. Initially they ornamented the Tanjore Court of King Sarabhoji circa 1800 as AstAna vidvAns. Likely AD 1825 or thereabouts the Quartet of brothers, fell out of royal favour, left Thanjavur and thereafter sought new patrons for their art. While Chinnaya found patronage in the Mysore durbar, Sivanandam and Vadivelu became the AstAna vidvans of Maharaja Svati Tirunal of Travancore. This background becomes important in the context of the fact that subject matter cauka varna in Telugu “sarasAlanu”’s sibling or clone “sUmasAyaka vidurA” is attributed to Maharaja Svati Tirunal himself and which ironically is more popular on the concert circuit.

It is quirky that, “sarasAlanu”’s very existence is unknown to many, save for the few cognoscenti today who may have heard it during the mid-20th century, featured in the dance recitals of the famous danseuse Balasarasvati, whose guru Kandappa Nattuvanar was a direct descendant being the great grandson of Ponnayya himself. It is no surprise that this composition of Ponnayya thus came to be part of Balasarasvati’s performance repertory. I will elaborate more on this in a little while.

Let us now look at the lyrical aspect of the cauka varna as well as the meaning before we proceed to dissect the melodic aspects of the composition.

Lyrics:

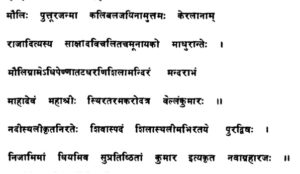

Cauka varna- raga Kapi – Tanjore Quartet Ponnayya

Pallavi:

sarasA ninnu Ipudu marimAnarA vinarA calamElarA (sarasA)

Anupallavi:

karunAkara ghanudaU vinu dhAri dI puna ithikO

nirathambuga iga jErarA brihadIsvara cAla

muktayisvara sahitya:

bAgAyarA prEmanunE ninnu nammi nAnu sArEku nu kAminula mOhamuna kunu sadaya

cakkani kucha mulnu kuliki nI jigibigi kAradhUla muddukanu nannu thAsOga sugA kalayarA samayamu (sarasA)

Caranam:

mAninI vErA nA sAmI

ettugada svara sahitya

- rA rA nA sAmigA jAlamElarA (mAninI)

- mA-na ghanamainamA- dhOravukAvu mA-tavina vEra mA-rasakumAra (mAninI)

- sAramuga jEra ninnu kOritijE vELanu dhayarani nuni ramana sAraganadA rakikA (mAninI)

Note: There is no sahitya for the 4th ragamalika ettugada svara section

It needs to be pointed out that the composer of this cauka varna as recorded is Ponnayya, the second amongst the brothers forming the illustrious Tanjore Quartet. The name is often confused with Tanjavur Ponniah Pillai (1888-1945), a Sangita Kalanidhi and another scion and descendant of the Tanjore Quartet being the great grand son of Sivanandam. This Ponniah Pillai too composed many musical pieces as well and therefore the reader should not be confused as between the Ponnayya of the Quartet and Ponniah Pillai his descendant of the 20th century.

Analysis:

The opening words as given in the book is ‘sarasA ninnu’ whereas the renderings and popular references to this composition have the opening words as ‘sarasAlanu’. As the lyrics would show, the Quartet’s mudra being “brihadIsvara” adorns the composition. It may be pointed out that Lord Brihadeesvara was the titular deity of the Tanjore Royals. The “Tanjai Nalvar Manimalai” of the Quartet’s descendant Sangita Kalanidhi K P Sivanandam assigns the composition to the authorship of Ponnayya and given this set of factors, it can be reasonably surmised that the composition was certainly composed when the brothers were in the Tanjore Court much before Vadivelu found patronage in Travancore.

It is likely that after Vadivelu became the astana vidvan in Svati Tirunal’s Court, he must have rendered his brother’s sarasAlanu before the Maharaja. Much enamored by its beauty, the Maharaja must have proceeded to ruminate and come up with the equivalent Sanskrit lyrics, with the appropriate svaraksharas and prAsA concordance to match the musical fabric of sarasAlanu. And thus, “sUmasAyaka” must have been born which had since then become ubiquitous given its royal ancestry eclipsing the original of Ponnayya.

I surmise that “sarasAlanu” was thus the one which was first composed when the Quartet ornamented the Tanjore Court, as it is vested with the mudra or colophon ‘brihadIsvara” which is seen in almost all compositions of the Quartet, when they are created during their Tanjore residency. After the brothers left the Tanjore Court, their compositions came to be invested with the pOShaka mudra or that of Padmanabha as in the case of Vadivelu. For example, Chinnaya’s Karnataka Kapi tillana “dhIM nAdhru dhIm dhIm” in Adi tala goes with the pOshaka mudra “cAmarAjendra” the Maharaja of Mysore. Similar is the case of the Kamalamanohari tana varnam in adi tala.

Prof R. Srinivasan in his erudite article “Music in Travancore” published in the Journal of the Madras Music Academy (Volume 19- 1948 – pages 107-112) makes this telling statement:

“Among the varnas, the one in Kapi beginning with “Suma Sayaka” is well known and at the same time technically of a high order. It is understood that Vadivelu influenced a large extent the music of it” (Emphasis is mine)

Therefore, for all the aforesaid reasons I would forcefully argue the case that sarasAlanu served as the model for sUmasAyaka and not the other way around. Though the two compositions can simply be labelled as clones of each other with much similarities, yet a few points of differences are seen between them, though melodically they are the same.

- To restate the obvious, “sarasAlanu” is in Telugu with “brihadIsvara” as the colophon, while “sUmasAyaka” is in Sanskrit with “sarasIruhanAbha” as the colophon.

- Both are set in Karnataka Kapi and in tisra eka tala in the cauka varna format with a pallavi, an anupallavi with muktayi svaras followed by a carana section with multiple ettugada svaras sections thereafter to follow.

- For both the varnas, the last ettugada svara section is structured as a ragamalika with 4 ragas, which finally segues seamlessly into Karnataka Kapi.

- Barring a few and minor differences in the music/svara setting, the three critical differences seen between the two compositions are as under:

- sarasAlanu has sahitya for the muktayisvara section of the anupallavi and for the ettugada svara sections of the carana; Whereas sUmasAyaka does not have such sahitya for the said sections.

- The final ettugada svara section of sarasAlanu features Hamir Kalyani, Vegavauhini, Vasanta and Mohana; sUmasAyaka instead has Kalyani, Khamas, Vasanta and Mohana. Each of the raga sub sections span 2 avartas of tisra eka tala of 3 beats each.

- The last tala beat of the final raga malika section in Mohanam directly transitions to the carana refrain ‘mAninI’ in sarasAlanu ; Whereas in sUmasAyaka the last tala beat of the final raga malika section in Mohanam has Karnataka Kapi svaras which then transition to the carana refrain

And without much ado let us first proceed to hear the composition before we embark on dissecting and learning some of the other aspects.

Discography – Part 1:

sarasAlanu is today all but forgotten. One may say that given its melodic identity being exactly like sUmasAyaka it did not survive. But the fact remains that sarasAlanu is unique for the aforementioned contrasting features and melodically distinct therefore from sUmasAyaka with the result that it deserves to survive, given it was the original one. Can we hear it today given that it is all but forgotten?

Luckily, we have a Vidushi in our midst, who had rendered this in a concert in the year 2010 and which was fortuitously recorded. I present the same being the rendering of Dr Ritha Rajan accompanied by Vidvans R K Sriramkumar and K Arun Prakash on the violin and mrudangam respectively.

The aforesaid recording was sourced from YouTube (see Foot Note 1). This is from the concert she gave for ‘Nada Inbam’ on 30-Aug-2010 at the Raga Sudha Hall, Chennai (See Foot note 2). In the original blog post on Karnataka Kapi, I had presented sUmasAyaka as sung by Sangita Kalanidhi Smt T Brinda. Readers may refer to the same to hear it once again.

The Musical Vista of sarasAlanu :

The raga Kapi, as we saw from the other blogpost, as seen in this composition has been chiseled from out of the native svaras of the 22nd Mela ( Sri Raga / Karaharapriya) going with the notes R2, M1, P D2 and N2. The arohana and avarohana krama as conventionally given is:

Arohana: S R2 M1 P N2 S

Avarohana: S N2 D2 N2 P M G2 R2 S

I should confess that this melodic representation does not convey the entire beauty of the raga. As the composition would show, the following features stand out:

- The gandhara note, even if occurring only in descent phrases is a strong note of the raga and comes in different shades. It is an (a)sadharana gandhara to state the least. Subbarama Dikshita in his SSP waxes eloquent on the gandhara of Todi as it occurs in the grand cittasvara section of the Kumara Ettendra classic “gajavadana sammOdita”. One can similarly revel in the different shades of gandhara in this composition.

- The descriptive grammar of the raga Kapi as seen in this composition can be given as under:

- In the purvanga ascent – SRGM, SRMP, RGMP are default murchanaas. It can be inferred therefore that SRGMP is forbidden. If the prayoga is SRGM it has to descend. Given that gandhara is “seen” omitted in the arohana, prayogas like SRGM or RGMP may sound quirky to us schooled in modern day musicology of the Sangraha Cudamani but yet these grammatical constructs are entirely in accordance with the principles of 18th Century musical architecture.

- In the uttaranga PDNS does not occur. PNDN descending back to Panchama and PNS proceeding to tara sadja alone are seen;

- SNP and SNDNP is the descent prayogas, eschewing the lineal SNDP completely.

- The lineal prayoga PMGRS is the one for purvanga in the descent.

- Gandhara and madhyama are presumably the jiva svaras of this raga imparting the greatest ranjakatva and figure both as the graha and nyasa svaras. The well oscillated gandhara is itself a leitmotif of this raga.

- pnR from the mandhara pancama , N\G in the Madhya stayi and PNDNPM, nG,R from the mandhara nishadha are some of the motifs of the raga.

- And above all in modern parlance, the raga is upanga and takes only the notes of the 22 Mela being catusruti rishabha, sadharana gandhara, suddha madhyama, pancama, catusruti dhaivatha and kaisiki nishadha only.

The Ragamalika section of sarasAlanu and a few questions around it:

An explanation is in order for the ragamalika ragas of sarasAlanu. The “Tanjai Nalvar Manimalai” calls out the second svara section albeit wrongly as Chakravakam. The examination of the raga malika svara appendage would reveal otherwise. The said svara section runs as under:

sarasAlanu (notation as found in the “Tanjai Naalvar Manimaalai”):

| Tala avarta of tisra eka | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Hamirkalyani | S, d, | ndpd | p,g, | p,md | pmgm1 | gm1r, |

| Vegavauhini (wrongly tagged as Chakravakam and with a possible printing mistake as srsm-gpmd-…..) |

srsm |

gmpd |

nsn, |

d,pm |

pdm, |

gm,, |

| Vasantha | gr,s | g,md | mdg, | md,n | sndm | ddn, |

| Mohanam | S,Rg | RSSd | ,pgp | d,pg | rspd | pSdp |

sarasAlanu (notation as per the pAtham of Dr Ritha Rajan)

| Tala avarta | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Hamirkalyani | S, d, | ndpd | m,gm | p,md | pmgm1 | gm1r, |

| Chakravakam | snsr | gmpd | nsn, | d,pm | pdm, | gm,, |

| Vasantha | g,rs | g,md | mdg, | mdns | ndmd | n,,, |

| Mohanam | S,RG | RSSd | ,pgp | d,pg | rspd | |

| Karnataka Kapi | psnp |

sUmasAyaka (notation as per notation published by Sangita Kalanidhi T K Govinda Rao)

| Tala avarta | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Kalyani | S, d, | ndpd | m,gm | p,md | ,ppm | g,gr |

| Khamas | snsm | gmpd | nsn, | d,pm | pdm, | gm,, |

| Vasantha | g,rs | g,md | mdg, | mdns | ndmd | n,,, |

| Mohanam | S,RG | RSSd | ,pgp | d,pg | rspd | |

| Karnataka Kapi | pn,p |

The above tables would show the following differences:

- The Hamirkalyani section in sarasAlanu and the Kalyani section in sUmasAyaka

- The difference in the Vegavauhini/Chakravaka section as between the two versions of sarasAlanu . It can be seen that in Dr Ritha’s oral tradition the svara progression is lineal as SnSRGMPDNSN,D,PMPDM,GM,, without the SMGM prayoga and hence can be called as Chakravaka.

- The difference in the svaras for the last beat of the tisra eka tala of the Mohana section in all the three versions, transitioning to the carana refrain ‘mAninI”.

While the Dr Ritha Rajan’s version of the second ragamalika section proceeds linearly as SnSR1GMPDNS… ., the version found in the “Tanjai Naalvar Manimalai” does not proceed linearly, which gives us doubt whether the second raga is Chakravakam as per the notation found therein.

It is quite plausible that Ponnayya being a disciple of Muthusvami Dikshita must have certainly known the raga lakshana of Vegavauhini which is the 16th mela raga in Venkatamakhi’s scheme and for which Chakravaka is the equivalent heptatonic scale. The notes of the svara section as found in the Tanjai Nalvar Manimalai corresponds exactly to the lakshana of Vegavauhini, vide the commentary for the same in the Sangita Sampradaya Pradarshini of Subbarama Dikshita. The opening murcchana of the raga being SR1SM1G3M1PD2N2S, eschewing the lineal SRGM is verily the signature of Vegavauhini as immortalized by Dikshita in his piece-de-resistance “vIna pustakadhArinIm”. In the face of these facts, it would be a travesty to tabulate the raga as Chakravaka and proceed to linearize and sing the same given Vegavauhini must have been the scale known to Ponnayya the composer of sarasAlanu and a scion of the Dikshita sisya parampara. It is on these sound grounds that it is argued that the second raga in the ragamalika ettugada svara section of sarasAlanu can only be Vegavauhini and not Chakravakam.

It must also be pointed out that in sUmasAyaka, both the ragas Hamirkalyani and Vegavauhini are seen flipped respectively to Kalyani and Khamas with a minimum of fuss. Further the flipping to Khamas (SnSMGMP) from SRSMGMP (Vegavauhini) sounds plausible, better than a flip from SnSRGMP (Chakravaka). Was the flip intentional or an accident or mistake in transmission that the ragas were flipped? For save for the R1 note, it would be virtually impossible to make out between a Khamas and a Vegavauhini. One doesn’t know!

Is sarasAalanu a svarajati or a padavarna:

The book “Tanjai Naalvar Manimalai” lists the composition sarasAlanu as a pada varna only. And to contrast, the Huseni composition “EmandayAnarA” is enlisted as a svarajati. As a rule, if a composition is invested with svaras and jatis being rhythmic syllables, it is more a svarajati than a pada varna. However, this boundary has now become blurred given that Syama Sastri’s creations in Bhairavi, Todi and Yadukulakambhoji are today labelled as svarajatis despite them lacking jatis in their body. Further as Prof S R Janakiraman persuasively argues, the nomenclature of ‘cauka varna’ would be more appropriate than ‘pada varna’.

Therefore, in all fairness, sarasAlanu which lacks jatis can and ought to be called a cauka varna or pada varna and certainly not a svarajati. Interested readers can refer to the article “Jatisvaram & Svarajati” by Dr Ritha Rajan in the JMA, mentioned in the reference section of this blog post herein below.

Placement of a cauka varna in a Concert:

In contrast to a tAna varna, the pada /cauka varnas, are more appropriate to be rendered right at the middle of a concert a little ahead of the main composition/pallavi. It can be seen that almost invariably all older cauka varnas are in rakti ragas which are melismatic by nature. The sedate tempo of the cauka varna together with a rakti raga being the subject of exposition through the cauka varna, adds a contrast to the concert, especially when it is sandwiched between madhyama kala compositions in contrasting ragas. I must hasten to point out exceptions do and always exist, such as for instance, Sangita Kalanidhi Govinda Rao has commenced a concert with the wondrous Surati cauka varna of Subbarama Dikshita “sAmi entani”. And I have personally heard the duet concert of Sangita Kala Acharyas Suguna Purushothaman and Suguna Varadacari, wherein they sang Svati Tirunal’s tour-de-force “dAni sAmajEndra gAmini” in Todi as the concert opener. And both these instances have been recorded for posterity.

In the instant case it can be seen from the concert recitals of Sri K V Narayanasvami that “sUmasAyaka” is rendered almost in the first half of the concert or just after the main piece. Even in the aforesaid rendering of “sarasAlanu” it is seen that Dr.Ritha Rajan has positioned it in the middle of the concert as seen in the listing from her recital- see Foot Note 2, during which this recording was made. As one can see that “sarasAlanu” has been featured right before the main or the piece-de-resistance of the concert and has been wedged between the ragas Kannada and Bhairavi.

Further in the context of rendering a cauka varna, it is noticed that while the pallavi, anupallavi and the muktayi svara and the corresponding sahitya are sung in a vilamba kAla, the carana line along with the ettugada svaras are rendered at a higher sprightly pace (Ottam ஓட்டம்). It is likely that this is a performance technique designed to prevent the concert from sagging, given the prolonged vilamba kala exposition in the first half of the composition. In the instant case of sarasAlanu as well it will be seen in the recording of Dr Ritha Rajan, that the rendering gathers pace from the carana portion “mAniNi vErA nA sAmI”.

Raga name- Is it Karnataka Kapi?

According to Dr Ritha Rajan, the raga of sarasAlanu/ sUmasAyaka being the upanga one bereft of anya svaras, the raga name ought to be simply Kapi. The term “Karnataka Kapi” was coined by Prof Sambamoorti much later and has no sastraic sanction otherwise. No musicological text or authority prior, make no mention of Karnataka Kapi. The version with kAkali nishAda can be called as Hindustani Kapi.

I should confess that while this proposition is attractive, we do have the versions of Muthusvami DIkshita (‘Venkatachalapate”) being the Kapi with traces of Kanada and or Durbar as in the case of versions of Tyagaraja’s kritis ‘nitya rUpa” or “anyAyamu sEyakura” which are bereft of distinguishing names to differentiate them from Kapi and Hindustani Kapi. It has to be pointed out that Subbarama Dikshita calls the raga only as Kapi but the version documented in the SSP is the one with the overwhelming flavour of Kanada. It’s a matter of record that some of the modern texts today even call this as Suddha Kapi.

Be that as it may it has to be on record that according to Dr Ritha Rajan the raga of sarasAlanu/ sUmasAyaka is Kapi. But as pointed out in my introduction, I have for the limited purposes of this blog post kept the name as Karnataka Kapi to differentiate it from the rest of the versions.

Origins of this pAtham of sArasAalanu :

While sUmasAyaka had taken roots in Kerala and had become an inextricable part of the dance repertoire, its foray into the Carnatic music stage was arguably through Sangita Kalanidhi K V Narayanasvami, who gave it a pride of place. See Foot Note 3

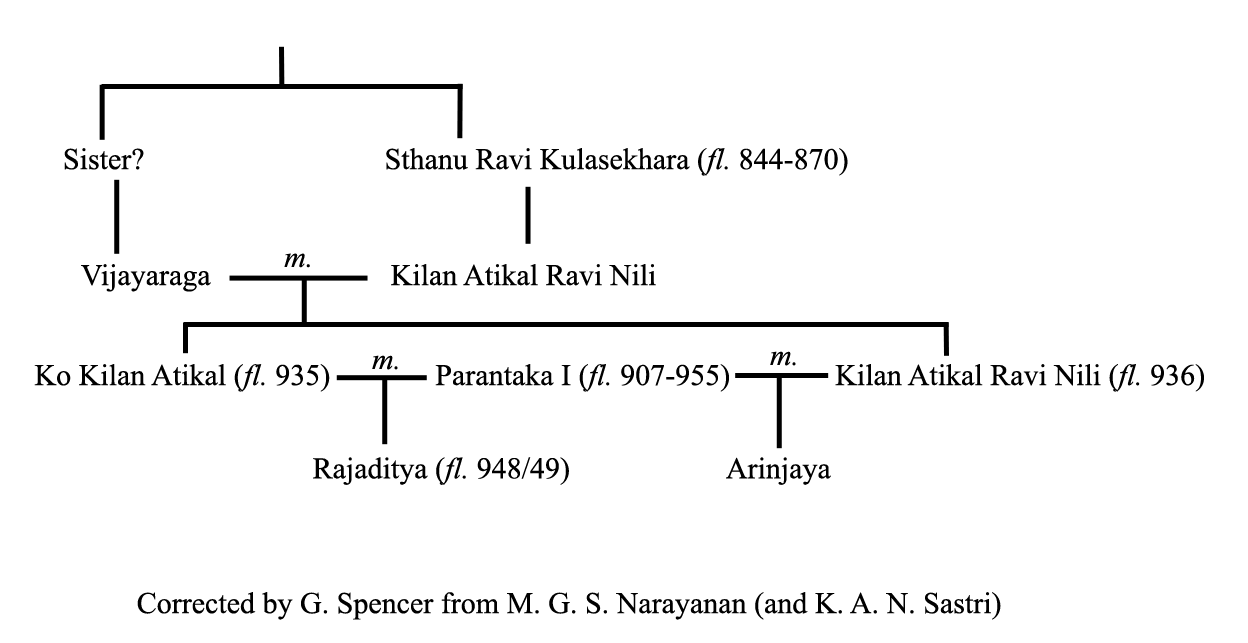

It can be surmised that sarasAlanu however continued to languish within the repertoire of the descendants of the Tanjore Quartet. After the life time of the 4 brothers and particularly the composer of the piece Ponnayya in 1864 AD the piece along with the rest of the crown jewels must have come to the possession of Nellayappa Nattuvanar (1850-1905), who was the grandson of Ponnayya. As T Sankaran recounts, Nellayappa Nattuvanar moved to then Madras and became a close acquaintance of the Dhanammal family. It was he who taught the family members including Jayammal, Balasarasvati’s mother popular javalis such as Vani Pondu (Kanada), Ela rAdayanE (Bhairavi) and JanarO E mOhamu (Khamas).

Nellayappa Nattuvanar died early and his son Kandappa Nattuvanar (1899-1941) therefore underwent tutelage under his uncle Kannusvami Nattuvanar (see family tree) at Tanjore and then moved to Madras when he became Balasarasvati’s (1918-1984) dance guru. It was under his tutelage and guidance that Bala ascended the stage in 1925, when she was just about 7 years old at the Ammanakshi Temple at Kanchipuram. As the conductor-in-chief of Bala’s dance ensemble, Kandappa Nattuvanar taught many pieces to the rest of the team. And amongst them was Sri Gnanasundaram who handled the vocals in Bala’s ensemble and he must have likely learnt sarasAlanu from Kandappa Nattuvanar. What we now know for sure in this entire narrative is that it was from Gnanasundaram that the legendary Vidvan Ramnad Krishnan (1918-1973) came to acquire this composition from after being so enamored of it. And he in turn taught it to Dr Ritha Rajan, his disciple whose rendering of sarasAlanu is featured in this blog. I have to point out that we do not have any recording of the rendering of sarasAlanu by any member of the Veena Dhanammal family including Sri T Visvanathan. See Foot Note 4.

And sadly, we do not have a recording of the Vidvan Ramnad Krishnan singing sarasAlanu. In this context we need to remember that the Karnataka Kapi seen in this composition is what is called as the upAnga version, which is bereft of anya svaras such as the antara gandhara (G3) or kakali nishadha (N3) or suddha dhaivatha (D1) which have come to be featured in modern day versions of the raga Kapi. It is worth recording here in the context of upAnga Kapi that it was Ramnad Krishnan again who learnt the jAvali “parulannamAta” of Dharmapuri Subbaraya Iyer in this upAnga version of Kapi from Rupavati Ammal, the younger sister of Vina Dhanammal who lived in Hyderabad and then rendered it often thus bringing it to the limelight.

Ponnayya – A Distinguished Composer:

I would argue further that sarasAlanu was the core for sUmasAyaka given the credentials and creative abilities of Ponnayya, of the Quartet. In fact, the perusal of the text of the Sangita Sampradaya Pradarshini would show that for two ragas namely Binnasadja and Camara, Subbarama Dikshita provides the kritis of Ponnayya alone as the authority for the respective raga lakshanas. In his commentary Subbarama Dikshita ahead of the Binnasadja kriti “srI guruguha mUrtikinE” (Mela 9) records thus:

This kirtana was composed by Ponnayya, who was the hereditary dance teacher of the Tanjore samasthana, and who was a disciple of Muttusvami Dikshita, was a great scholar in the laksya, and lakshana aspects of bharata sastra and who had also earned fame by composing numerous svarajatis and varnas, suitable for dances.

That apart under Malavagaula (Mela 15), the kriti “mAyAtIta svarUpini” of Ponnayya has also been provided as an exemplar by Subburama Dikshita. It is however unfortunate that we hardly rely upon the compositions of the Quartet as authority for raga lakshana, when even Subbarama Dikshita had done so without any reservations whatsoever.

This demonstrated and acknowledged composing mastery of Ponnayya is another aspect that supports the proposition/conjecture that sarasAlanu was composed earlier by Ponnayya. much prior to the Quartet’s migration to the Travancore Court. No further evidence is therefore needed to conclude that Ponnayya was a composer par excellence and the authorship and originality of sarasAlanu and its tune can without doubt be ascribed to him, without any doubt whatsoever.

And so, every time one hears the Karnataka Kapi of sUmasAyaka we should for a moment recall the aesthetic construct of the varna and the raga therein. Hark at the different shades of the gandhara of mela 22 as well as the placement of the svaraksharas such as on the madhyama note which will evoke awe spontaneously. The credit for this conceptualization should undoubtedly go to Ponnayya of the Quartet, the illustrious disciple of Muthusvami Dikshita. To clarify, this is not to belittle or discredit Maharaja Svati Tirunal or call into question his compositional abilities in any way. As in the case of “gana nAyakam” and “srI mAnini”, the Maharaja was perhaps left smitten by the melodic fabric of sarasAlanu that he went on to compose another set of lyrics for it out of sheer love for the melody of sarasAlanu.

And thus here, all that is sought to be argued is that sarasAlanu was anterior in time composed by Ponnayya, the Maharaja after hearing it later in time composed sUmasAyaka to the same mettu/dhatu and that the preponderance of evidence on hand and of probability as well, firmly supports this line of reasoning.

Further in the context of ragamalikas, it is seen that it was part of the kriti format even prior to 1800’s, as evidenced by the compositions of Melattur Virabhadrayya and Ramasvami Dikshita. And the family of Dikshitas reveled in composing ragamalikas. Having been under the tutelage of Muthusvami Dikshita, the Quartet seem to have warmed up to this concept of stringing in ragas so much so that sarasAlanu came to be appended with a ragamalika ettugada svara section, which to my best of knowledge is not seen in any pre 1830 AD composition of the genre of varnas. This piece of melodic engineering can perhaps only be very much confidently ascribed to the Quartet’s tutelage under Muthusvami DIkshita.

Discography Part 2:

Even as I had almost finished composing this fairly long blog post, as if in answer to my wish, my co-rasika acquaintances- see Foot Note 5 – mailed me the entire 45-minute recording of the rendering of sarasAlanu by Balasarasvati’s famed ensemble presumably from one of her dance recitals. The audio recording also has the sound of the bells of Bala’s anklets as well.

Here is the audio uploaded to Youtube:

T Balasaraswati and Troupe | Raga Kapi | Sarasalanu Ipudu (Varnam) – YouTube

And this recording for sure features the following artistes/Vidvans – vide Foot Note 6 below.

Kanchipuram Sri. C. P. Gnanasundaram alias Gnani and Sri Narasimhulu – Vocals ;

Sri Radhakrishna Naidu – Clarinet; Kanchipuram Sri Kuppuswami Mudaliar – Mridangam

T Vishwanathan – Flute with Ganesan Pillai – Nattuvangam

After the demise of Bala’s mother Jayammal (1890-1967) Vidvan Gnanasundaram hailing from Kanchipuram assumed the mantle of the lead vocalist of the ensemble. Trained by Naina Pillai’s disciple Villiambakkam Narasimhachar he was an accomplished singer having sung in the Music Academy for instance in the December 1959 season and a graded AIR artiste as per archived records of the “Indian Listener”.

Sri C.P. Gnanasundaram. and Sri. Narasimhulu were concert musicians of high order. Their rich musical flow matched the incessant interpretative expertise of T. Balasaraswati in an outstanding manner so much so that each of Bala’s performance with this orchestral team made an unforgettable experience. And each of Bala‘s orchestra members were exponents in their own right. Upon the premature demise of Bala’s Guru Kandappa Pillai in 1942, Ganesan (1924 – 1987) his son took over as the conductor-in-chief of her ensemble. See Foot Note 7.

This audio recording which must be dateable at the latest to circa 1965, is also a snippet encapsulating history entwining the successive descendants of Carnatic music and dance’s great first families, the lineage of the Quartet and that of Tanjavur Pappammal whose lineage we today know, as the Veena Dhanammal’s family.

Dhanammal’s great great grandmother Tanjavur Pappammal was part of the Tanjore Court and her granddaughter Tanjavur Kamakshi (1810-1890) left Tanjore Court along with Sivanandam and Vadivelu of the Tanjore Quartet to Travancore. Tanjavur Kamakshi’s granddaughter was Veena Dhanammal. And her granddaughter Balasarasvati went on to have Kandappa Nattuvanar, a great great grandson of Ponnayya of the Quartet as her guru and later his son Ganesha Pillai as the conductor-in-chief of her ensemble.

The recording of sarasAlanu by Bala’s ensemble is thus a vista or a montage of the very history of our fine-arts, tradition and musical excellence. Decades have flown by since this recording had been made and I now wonder how the diva of our dance must have captured abhinaya for this wonderful piece, holding the audience spell bound for 40 or so minutes , all the while competing with the rapturous melody and the lyrics and with all of them vying for the rasika’s attention.

Conclusion:

sUmasAyaka has had considerable airtime in the past decades. As pointed out earlier, the late Sangita Kalanidhi K V Narayanasvami used to render it quite regularly in his concerts. We do have the Bombay Sisters having cut a record of the same. In modern times Vidvans T M Krishna, Ramakrishnan Murthi and others have presented the composition quite frequently. See Foot Note 8.

My first encounter with sarasAlanu was when Smt Sundari, wife of Prof C S Seshadri sang for me the composition so beautifully, one summer evening more than a decade ago. I now recollect from my conversation with her that she too had learnt it from Vidvan Narasimhulu of Bala’s ensemble. Sadly, I failed to record her rendering then.

Alas thus practically sarasAlanu lies unsung and forgotten, save for Dr Ritha Rajan’s solitary rendering presented above. Even on the Bharatanatyam stage, sUmasAyaka now rules the roost. Apparently even Bala stopped performing this piece past the 1960s. With passage of time, compositions so unique like sarasAlanu will be completely forgotten and would be lost forever unless the succeeding generation learns and perpetuates the cycle of transmission.

sarasAlanu in the beautiful Karnataka Kapi is an aigrette deserving to be sung and burnished further. One hopes as always that modern day performers would take it up learn and present it in its pristine and full form frequently, including the rendering of the sahityas of the muktayi and ettugada svaras. And whenever we get to hear this composition, one should pause for a moment and remember every one of the giants from the past starting from Ponnayya of the Tanjore Quartet on to his grandson Nellayappa Nattuvanar and on to Kandappa Nattuvanar his son and then on to Ganesa Pillai & Gnanasundaram of Balasarasvati’s ensemble and to Vidvan Ramnad Krishnan and finally today on to Dr Ritha Rajan. Had it not been for this long, glorious and unbroken lineage of gurus and sishyas, starting from 1830 AD or thereabouts, we would not have been able to savor this composition today. May this glorious parampara continue so that the composition sarasAlanu will live on for many more generations to come.

Post-script:

Purely as an aside, I venture to conclude this post with a humorous anecdote. The beauty of the notes/svaras gandhara (G, க in tamil) and madhyama (M, ம in tamil) that have been beautifully and tellingly used in this composition reminds me of a quip reportedly made by the legendary Smt T Brinda, the source of which I am unsure. It seems once she was listening in to an All-India Radio (AIR) Arangisai broadcast of Vidvan D K Jayaraman and in it he was rendering Tyagaraja’s “nEnaruncarA nA pai” in Simhavahini. And the Vidvan after rendering the kriti apparently launched into an imaginative svara prastara sally on the pallavi line as “gm gm g, m- (nEnaruncarA)” and so on in succession, pivoting on the “gm-gm” janta phrase. Bemused, the doyenne upon the conclusion of the piece, reportedly remarked in jest in a style typical of her, making a play on the notes/words thus- “ஐய்யரு கமகமனு மணக்க மணக்க பாடறாரு”. In the instant case it is perhaps the gandhara and madhyama notes making the “kApi” or “kAfi” (as its Northern counterpart is usually referred to) of sarasAlanu, melodically fragrant (கமகம) made me recall Smt Brinda’s witty comment.

References:

- 1984- T Sankaran – Article “Kandappa Nattuvanar” (English)– Journal of the Sangeet Natak Akademi – No 072-073 (April- September 1984) -pp 55-59

- 1984 – T Sankaran – Article “Bala’s Musicians” (English) – Journal of the Sangeet Natak Akademi – No No 072-073 (April- September 1984) -pp 61-65

- 1940 – K P Sivanandam – “Tanjai Nalvar Manimalai” (Tamil) – Reprinted in 2002 -IV Edition -pp 73-75

- 1948-Prof R Srinivasan– “Music in Travancore” (English) – Journal of the Music Academy of Madras (JMA) Vol 19-Edited by T V Subba Rao and Dr V Raghavan -pp 107-112

- 2017 -Prof B Balasubramanyam, University of Wesleyan – “Music of Balasarasvati”- Lecture Demonstration at the Madras Music Academy on 22-December 2017 – Journal of the Music Academy of Madras (JMA) -Volume 89 (2018)- Edited by V Sriram – Report of the Daily Proceedings of the Annual Conference of 2017- pages 19-20

- 2010-Douglas M Knight – “Balasaraswathi -Her Art & Life” – Published by Tranquebar Press- Chapter 2 titled “Madman at the Gate”- Pages 49-59

- 2017 -Dr Ritha Rajan – Article “Ramnad Krishnan” – Journal of the Music Academy of Madras (JMA) – Volume 89(2018) -Edited by V Sriram -pp 44-50.

- 2002 -Dr Ritha Rajan – Article “Jatisvaram & Svarajathi” – Journal of the Music Academy of Madras (JMA)- Volume LXXV (2002) -Edited by Sri TT Vasu & Nandini Ramani -pp 68-88

- 2019 – Compilation of Balasarasvati’s Repertoire – (English)– “Sangeet Natak”- The Journal of the Sangeet Natak Akademi – Vol LIII (Numbers 1-4 2019) -pp 117-122

Foot Notes:

Note 1: The recording of sarasAlanu from Dr Ritha Rajan’s concert has been sourced from the Youtube account of Krishna Narayanan which can be found here. I am thankful to him for sharing the rendering.

Note 2:The details of the concert are recorded in the blog post of a rasika Sri Bharat, which can be read here. The list of composition featured in the recital, seriatim is as under:

sAmi nI pai – Anandabhairavi – aTa – Veenai Kuppayyar (short sketch of raga) [varNam]

rAmA nI pai – kEdAram – Adi – Tyagaraja (short sketch of raga and svarams)

kAntimati – kalyANi – rUpakam – Subbarama Dikshitar (Raga alapana)

idhE bhAgyamu – kannaDa – misra cApu – Tyagaraja (Ragam & Svaram)

sarasAlanu ipuDu – Karnataka KApi – rUpakam – Tanjore Quartet (short sketch of raga)

nI pAdamulE gatiyani – bhairavi – Adi – Patnam Subramanya Iyer (Ragam Neraval Svaram followed by Tani avartanam)

koNTE gADu – suruTTi – tisra tripuTa – Ksetrajna padam

marubAri – senjuruTTi – rUpakam – Javali – Dharmapuri Subbarayar

rAkA chandra samAna kAnti vadanAm – slOkam from mUka panchasati – aTANA, nAyaki, sahAnA, yadukula kAmbhOji

kAraNamadAga vandu – sindhu bhairavi – kaNDa tripuTa – Arunagirinathar [tiruppugazh]

nI nAma rUpamulaku – saurAshTram – Adi – Mangalam – Tyagaraja

The entire concert is now posted to YouTube: Vidushi Ritha Rajan for Naada Inbam Vintage series “Music heals” – YouTube

In the recording of Dr. Ritha Rajan’s rendering, an alert listener can discern from her remarks at the conclusion of the recording, that the same is from this particular concert as she also refers to the Kalyani composition (“kAntimati”) of Subbarama Dikshita in response to a query from a rasika, which she had rendered ahead of sarasAlanu in the concert. As one evaluates the concert listing above, one can’t but admire the Vidushi for her selection, placement and spread of the compositions, the choice of ragas including those for the sloka as well, imparting the aesthetic balance and wholesomeness to the concert recital. Again many thanks are due to “Nada Inbam” for having recorded the concert for posterity and to Parivadhini for taking the time and effort to get this concert uploaded on to YouTube

Note 3: It is on record through T Sankaran, that when Sangita Kalanidhi T Brinda was roped in to provide musical training to the Royals of Travancore, she took residency in Trivandrum briefly during which time quite a number of Svati Tirunal compositions were learnt by her which explains how sUmasAyaka and valaputAla the padam in Atana, came to find place in her repertoire. It may be news to many that the doyenne apparently also learnt a bunch of Svati Tirunal compositions from Sri Semmangudi Srinivasa Iyer, when she was roped in to give an AIR National program concert exclusively of Svati Tirunal compositions. I haven’t come across the recording of the said radio concert and I wonder now if the recording of her singing sUmasAyaka was from that concert.

Note 4: The legendary Veena Vidvan S Balachandar a vociferous advocate of the school of thought that Maharaja Svati Tirunal as composer was just a perpetuated myth, was so enthralled by “sarasAlanu” that he would ask his disciple Smt Gayathri Narayanan to play it. Again, we have no record of a rendering by the maestro or his disciple.

Note 5: I am in great gratitude to Krishna Narayanan again for digging out the complete track of sarasAlanu as rendered by Smt Balasarasvati’s ensemble for her performance and to Shreeram Shankar for hosting and sharing through his curated Vaak YouTube channel.

Note 6: I am greatly indebted to our family friend Ms.Sushama Ranganathan & her mother the respected Smt Nandini Ramani for confirming the identities of the performers in this clip, first hand and providing inputs as to the composition’s provenance and its rendering by Smt Balasarasvati’s ensemble. Smt Nandini Ramani, daughter of Dr V Raghavan was one of the senior disciples of Smt Balasarasvati herself and her daughter Ms.Sushama Ranganathan was trained by Ganesa Pillai, the son of Kandappa Nattuvanar.

Note 7: It is a pity that these great artistes were never duly recognized and life too wasn’t kind to them. Vidvan Gnanasundaram contracted leprosy even as he was part of Bala’s ensemble and yet Bala ensured he was part of it nevertheless and he died prematurely. These artists ultimately died unwept and unsung and possibly many in penury. For instance, here is what T Sankaran writes (circa 1984) of Kuppusvami Mudaliar alias Kuppanna who provided the mridangam accompaniment which is heard in the audio recording:

“Kuppanna is today living in Kanchipuram, pining away in infirmity, clutching his empty purse, feeding on his glad memories of his halcyon days and the bad memories of his ungrateful son a Tahsildar who predeceased him.”

Ganesa Nattuvanar, died a bachelor much of his time in drunken stupor with nothing to sustain him. And alas with him the branch of the Ponnayya line of the Quartet came to an end. One should be thankful to the late Sri T Sankaran for having recorded at the least a brief biography and the contribution of these artistes, who made a Bala recital a delectable experience, in the Sangeet Natak Akademi Journal article “Bala’s Musicians”, given in the references section, without which we would have never known even the very existence of these great artistes.

Note 8: The composition sUmasAyaka is also part of the audio track of the Malayalam movie “Swati Tirunal” wherein it has been sung by Ms.B.Arundhati. The composition is also part of the Mohiniyattam repertory of compositions and occupies a pride of place in the quartet of varnams along with ‘dAni sAmajEndra’ (Todi), ‘manasimE paritApam’ (Sankarbharanam) and ‘hA hanta vanchitam’ (Dhanyasi) presented by the Kalamandalam school/tradition of Mohiniyattam and choreographed by the high-priestess of the tradition Smt Sathyabhama (Source Ms Sapna Govindan – “Tradition in Mohiniyattam” – available Online)

Acknowledgments:

I am deeply in debt to Dr Ritha Rajan for providing me the time, patiently answering all my questions and for clarifying or validating many points as to this composition and its nuances and antecedents, without which this blog post would not have been complete. The photographs of Kandappa Nattuvanar and Ganesa Pillai has been taken from the Sangeet Natak Akademi Journal and the others have been sourced from the internet.

Disclaimer:

I have endeavored to present the information, facts and the inputs received from the named individuals including Dr Ritha Rajan to the best of my abilities and understanding. The arguments that I have advanced or the opinions I have expressed is independent of their viewpoints /inputs and the individuals concerned do not necessarily subscribe to the same nor do they acknowledge it as their point of view.

The renderings have been in the public domain and the copyrights if any for the performance thereof continues to be exclusively of the respective performers/authors. No part of this blog or its contents shall be commercially exploited.