[simple-author-box]

Note:

This article is a rejoinder to the views questioning Kshetrayya’s existence in an article by Dr.Swarnamalya Ganesh that appeared in the NewsMinute.

For those who listen Karnataka music, Kshetrayya needs no introduction as he is one amongst the few who has composed compositions brimming with srungara rasa. He can be very well placed in the line of few Azvar-s like Tirumangai Azvar or Andal and Jayadeva. It is commonly believed that he hails from the place called Muvva and he was a devotee of Lord Krishna enshrined there. He takes the role of a nayika and his compositions are intimate love dialogues between him and his Lord. Kshetrayya’s compositions are well known for his free and lucid style with an absorbing music.

I happened to read an article by Swarnamalya Ganesh on Kshetrayya and his creations, pada-s with the mudra ‘muvvagopala’. She claims the compositions were actually composed by courtesans and they were appropriated to give a ‘male voice’ to those erotic lyrics. This article by Swarnamalya also quotes another article by Harshita Mruthinti Kamath who even claims Kshetrayya was a figment and was created by the literary community. These two articles shake the belief that Kshetrayya can be no more called as a vaggeyakara as the compositions bearing the mudra ‘muvvagopala’ are in reality, the voice of courtesans. Though it is imperative to attribute the compositions to the composer who conceived it, we need to first analyze the quality of the research that has taken place to call Kshetrayya as a figment. The readers are requested to read the article by Harshita and Swarnamalya before proceeding further. This article will be analyzing the arguments placed by them and an analysis will be provided from the angle of a music researcher.

This article can

be divided into two parts – first part deals with the theory that Kshetrayya is

not a historical figure but a later construct and the second one with the

authorship of the pada-s of Kshetrayya.

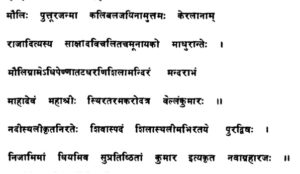

Let us see the

various literary evidences that mention about Kshetrayya. Before going to this,

it is to be admitted that the details of this poet available from the literary

sources are very scant. The first evidence that we get comes from Manda

Lakshminarayana, a 17th or 18th century poet who wrote

the text ‘Sarasvati Trilinga Sabdaanusaasanam’ also called as ‘Andhra Kaumudi’,

a text on Telugu grammar. He remarks Kshetrayya as ‘iti muvvagopala bhaktena

ksetra kavinaa uktatvaacca’, meaning ‘as said by the poet Ksetra, a devotee of

Muvvagopala’. What can be understood from this is that the kavi ‘Ksetra’ was

popular for using the mudra ‘muvvagopala’, being a bhaktha of the Lord

Muvvagopala. This (text) occurs as a continuation of a verse praising Ragunatha

Nayaka in the reference mentioned. 1

Supplicants come on their own

to a patron who knows how to give.

Who invited them?

Don’t bees visit the lotus pond

on their own,

king Raghunatha?

Harshita raises

following queries:

‘insertion of this line and attributed author is interesting for three reasons: first, the line is written in prose, which does not match the lyrical poetic style of the padam genre. [sic] Second, the line is dedicated to Raghunātha Nāyaka (r. 1612–34), who is the predecessor of Vijayarāghāva Nāyaka (r. 1634–73), the latter of whom is the king commonly thought to have patronised Kṣētrayya as per the mēruva padam. [sic] Finally, the poet is identified as Kṣētra, not Kṣētrayya or Kṣētrajña, a Sanskritised version of the poet’s name’. [sic]

Let us see one

by one in detail.

Style of the text

Harshita starts

by saying the text does not confirm with the style padam-s, the genre for which

Kshetrayya is known for. When we don’t even know the proper life history of

Kshetrayya, his exact number of compositions and the location where he exactly

hailed from, is this not a hasty conclusion that he could have composed only padam-s

and this text is out of place? Why should we not think he has composed a text on

Raghunatha Nayaka or some other theme where this line features in?

The verse on Raghunatha Nayaka

As mentioned

earlier, we do not know the exact time period of Kshetrayya. From his various

compositions and the internal evidences therein, it can be understood he lived

during the period of Vijayaragahava Nayaka and patronized by him. We also

understand he was patronized by two other kings, Tirumala Nayaka of Madurai and

Padsha of Golconda from his meruva padam. In the meruva padam, which we will be

seeing it soon, he refers to Tirumala Nayaka of Madura, followed by

Vijayaraghava Nayaka and the Padsha of Golconda. If we place them in the

timeline, Tirumala Nayaka is anterior to Vijayaraghava Nayaka, the former

reigned Madurai from 1623-1629 and the latter ruled Tanjavur from 1633-1673. This

implies Kshetrayya should have lived in the early part of 17th

century. What is interesting here is the reign of Tirumala Nayaka coincides

with that of Raghunatha Nayaka (1613-1631). Hence the possibility that

Kshetrayya could have visited the court of Raghunatha Nayaka and patronized by

him cannot be denied. We wish to remind the readers that not all the padam-s of

Kshetrayya are extant. Subbarama Dikshitar has mentioned, he had 700 padam-s of

Kshetrayya; only around 200 or 300 are in circulation now. So, the number of

padam-s handed over to the next generation is always in decline and one of

these lost padam-s might have a reference to Raghunatha Nayaka! This link was strangely

missed by Harshita!

Name of the kavi

The text that we

quoted read as ‘kshetra’ and not as Kshetrayya or Kshetragna. Harshita raises a

query ‘were the poet Kshetra and Kshetrayya are same’? It is distressing to see such an argument from

a scholar who has worked on Telugu literature. The word ‘ayya’ is used as a

form of respect and is usually added as a suffix to a person’s name. In this

case, Kshetra has become Kshetrayya as a token of respect. Do we have to

believe her inability to make this out is a happenstance?

The next

reference is from Raghava Chary in his book written in the year 1806.1

Cashatreya, a modern Poet of first note, who composed innumerable Padasmarked with the name of Moova Gopala (Kristna) [sic] – his style is elegant and musical; his language is easy and clear, and his meaning is comprehensive

Though

Cashatreya is a variant, we can again see his name is being associated with the

deity Muvvagopala. What we wish to reiterate is Kshetrayya was always treated

synonymously with his deity Muvvagopala throughout the literary history. But

his life history was not mentioned in any of the mentioned references. The

first information about his personal life comes from Subbarama Dikshitar in his

Sangita Sampradaya Pradarshini.2 He was the first one to mention

about his initiation into Gopala mantram and he was from Muvvapuri. Dikshitar

also mention various incidents happened in the life of Kshetrayya and perhaps

he was the first to call him as Kshetragna.

We have two other evidences that say about Kshetrayya before the

publication of the book by Vissa Appa Rao in 1950s and these two were missed by

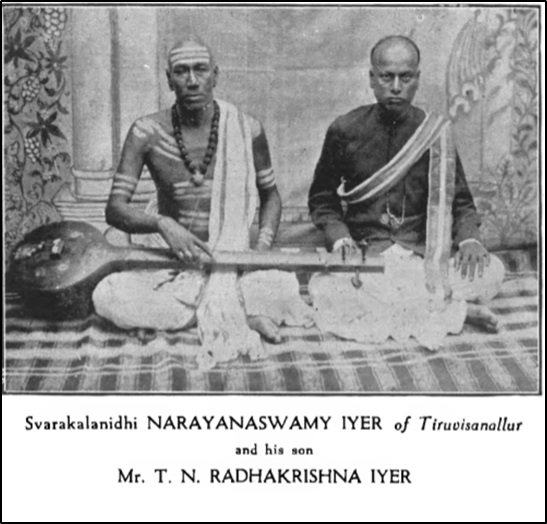

Harshita. The first one is the book Gayaka Siddhanjanam by Taccur Brothers

published in the year 1905.3 Their mention is very brief and they

say he was a composer of 1000 love songs and lived in a place by name Muvva. The

second one is more important as it is from a believer of different faith,

Abraham Panditar.4 He has mentioned Kshetiriya has composed 1000

padam-s, mainly reflecting the srungara rasa with the mudra muvvagopala. Further

down the line, we find an elaborate story on Kshetrayya’s personal life by

Vissa Appa Rao and Rajanikanta Rao. We do not want to dwell into that as they

are the author’s interpretation of the available evidences and might lack

historical authenticity. From the discussion above, we can understand there

existed a poet by name Kshetra/Kshetrayya/Cashatreya/Kshetriya during the reign

of Tirumala Nayaka and Raghunatha Nayaka, who could have reached the zenith of

his career during the reign of Vijayaraghava Nayaka. He was known for his

srungara padam-s, though the exact number is not known. He was always

associated with the mudra ‘muvvagopala’ due to his intimate attachment with the

Lord Gopala of Muvva. Various places contest to get identified with the Muvva

of Kshetrayya and we do want to venture into it, as it will make us to deviate

from the topic.

Meruva padam

Almost every other who has given a detailed description about the padam-s of Kshetrayya mention this padam ‘vedukato’ in the raga Devagandhari, also called as meruva padam.

When Tirumala, the king of Madhura, lavished me with gifts

and ordered me to sit before him in his assembly,

he asked: ‘Give me the best of your poems’.

I responded, ‘Here’s 2,000 poems. Pick your favorite’.

Seated on a stage, the king was immensely overjoyed.

He’s the best of customers who plays with joy.

I saw Vijayarāghava in Tañjāvuri in a resplendent garden,

seated under a cool canopy.

When I talked to him, composing 1,000 songs,

he showered me with gifts.

He’s the best of customers who plays with joy.

When the strong Pāduśā of Gōlakoṇḍa gave gifts to me

he conversed with Tulasimūrti that day.

Muvva Gōpāla sang 1,500 songs in 40 days, all through me.

He’s the best of customers who plays with joy1

This is

the common padam used to date the period of Kshetrayya and Harshita again

places a few queries. She argues there is no reference to Kshetrayya and this

is not in the style of other padam-s with the mudra ‘muvvagopala’. Let us look

in to these issues now.

Period of Kshetrayya

Every

composer, at least in one of his composition gives an internal evidence about

himself. It might be some important event that happened in their life or about

his parents or about his place of origin. In this padam, we find the names of

three rulers – Tirumala Nayaka, Raghunatha Nayaka and Padsha of Golconda and how

the author of this composition was honored by every one of them. At the end of

the padam, all the glory to the composer were attributed to the deity Muvvagopala.

We have seen in all the earlier evidences, including the one by Abraham

Panditar, that Kshterayya has made an indelible mark in the mind of people with

two pointers – one by composing predominantly srungara padam-s and the second

one by associating himself with the deity Muvvagopala. None of the grantakara-s

seen above has mentioned him to use ‘svanama’ mudra (his name as a mudra). Hence

it is much clear that Kshetrayya was the composer of this padam. Understanding

vageeyakara-s (not poets) is important when we try to date the period of a

composer and this lack of understanding, perhaps made Harshita to raise this

query.

Style of the padam

Harshita mentions this padam differs

from the rest of the padam-s with the mudra ‘muvvagopala’ which typically

involve a female lover speaking to a friend or lover. A careful examination of

few other padam-s could have avoided this confusion. Let us cite two examples:

I offer you worship in ever so many ways,

O ! Lord unite her with me !!

For having supplicated you to such an extent

O ! Lord fulfill my desire !!5

– Inni vidhamula (Mukhari)

When I am unable to bear the onslaught of Cupid,

are you angry, Muvvagopala that I aspire for your love ?5

– Sripati sutu (Anandabhairavi)

Both the

examples cited are his personal communications with his Muvvagopala and nowhere

an emissary or a pining lover is involved. As we have mentioned, every composer

furnishes his creations with internal evidence and the meruvu padam is one such

example similar to the two padam-s cited here.

Article with no convincing evidence

We have

cited various lacunae on the way by which the research by Harshita was carried

out. Let us look into one more issue of that sort. A research article is

supposed to have a hypothesis affixed with plausible evidences. Strangely here

in this article, we find a conclusion but with no acceptable explanations! Nowhere

in this article, was she able to prove Kshretrayya never existed! She is also

of the opinion that the padam-s with the mudra ‘muvvagopala’ were composed by

courtesans or nattuvanar-s. Again no evidence for this too can be seen in her

article and we will elaborate this in the next section.

Kshetrayya is not a figment

We have placed coherent counter arguments for

the erroneous statement made by Harshita on Kshetrayya, without giving any solid

evidence. Anyone who goes through the

available evidences (provided here or elsewhere) can easily make out that Kshetrayya

is indeed a historical figure, who has composed with the mudra ‘muvvagopala’. It

is accepted that the details about his life history are very scanty in the

written literature. Many

of our oral histories exist as oral traditions, fragments due to repeated

invasions and ravages of time. So unless we have a clear evidence of absence we

cannot conclude that the absence of written evidence or history should say that

Kshetrayya doesn’t exist.

Who is to be credited?

We will now concentrate on the next segment, on the authorship of the padam-s with the mudra ‘muvvagopala’. The seeds of this query was planted by Harshita and was nourished by Swarnamalya in her recent article. Harshita states:

‘I raise the possibility that vēśyas composed these Nāyaka-period padams’ [sic]

and Swarnamalya continues as:

‘she does not however delve into the possible names of poetesses and courtesans, which I endeavor to do’ [sic]’

Before seeing these arguments in detail, let us understand that Devadasi-s were custodians of the padam-s of Kshetrayya (along with other musical forms that deal with srungara like javali-s) and they consider as a perquisite with great pride. Many of these compositions were known only to them and even now, we might get some unpublished compositions from their descendants. In other words, it can be said Devadasis were mainly responsible for the propagation of Kshetrayya padam-s. The authors Harshita and Swarnamalya believe the works of these courtesans were appropriated and given a male voice to make these erotic songs more palatable. On analyzing the articles mentioned, we get the following questions:

- When did this

appropriation take place?

- What are the

evidences to say courtesans were the composers of these padam-s and why did every other courtesan use the

mudra muvvagopala?

- Why were the works of courtesans

alone appropriated?

- Do we have a history of males writing

about women-specific expression?

When did this

appropriation take place?

Though the scholars keep reiterating the works of courtesans

have been appropriated, they never came with a hypothetical period during which

this could have occurred. Absence of this information even in a full length

research article, like that of Harshita is glaring. Now, let us dissect the

possibilities of this appropriation.

From

the above discussion, it becomes clear Kshetrayya lived during the period of

Nayaka dynasty. Let’s imagine that was the period these padam-s could have been

written by the courtesans. Also, we can understand from the discussion of the

scholars that, the sanitization of the art of South Indian dance and the

implementation of Anti-nautch Act, in association with the colonial mentality

is mainly responsible for repugnance towards the erotic works. So, the

appropriation could have taken place by the second half of 19th

century and/or the first half of 20th century. This raises two

pertinent questions – we have a reference to the kavi Kshetrayya and his

association with the deity Muvvagopala by Manda Lakshminarayana Kavi, written

during 17/18th century. How can this be accounted? Going by this

evidence, if at all, the padam-s were appropriated, it could have happened

before the period of Lakshminarayana Kavi, which could be before 17th

or 18th century. If that is the case, what was the need to

appropriate when there was not a generalized aversion to srungara rasa? We

could not even find a discussion in these lines in the article mentioned, leave

alone an explanation.

What are the

evidences to say courtesans were the composers of these padam-s and why did every

other courtesan use the mudra ‘muvvagopala’?

As mentioned elsewhere, when a researcher places a hypothesis,

he/she is expected to affix it with evidences. What evidences do we have to say

these ‘muvvagopala’ padam-s were composed by courtesans? Harshita’s article

does not have any explanation and Swarnamalya mentions:

‘Nayaka period repertoires, there was one Nava padamulu [sic]. Nava to mean new, contemporary padams by a variety of composers, were performed in the court every day [sic]. Several of the “now attributed to Kshetryya” padams debuted there, through the courtesan voice and never in that of a Kshetrayya’s [sic]’.

The details of the manuscript, paper or palm leaf

preferably with the catalogue number, padam-s featured therein, the name of the

composers therein, whether the names are found in association with padam-s or

in a separate folio, any evidences of that manuscript being copied earlier etc.,

are to be furnished to be more subjective. Though it is an article in an online magazine,

it is intriguing that, not even a name of a single composer purported to have

composed these padam-s has been mentioned. Even if the argument is made

that some of these expressions are typically female, there is plenty of

reference in literature including Kamasutra of Vatsyayana where males

articulate from the female standpoint. Many Sangam era poets were male who

wrote from the viewpoints of female. So this is nothing new within the larger

cultural framework.

Now comes a yet another a germane question – what is the

reason for so many courtesans to compose the padam-s with the mudra

‘muvvagopala’? Mudras are insignia of a composer making us to identify the

author of a given composition. Mudras can be of various types – svanama (his

own name), poshaka (patron’s name), sthala (place with which he is associated)

and so on. A single vaggeyakara can use multiple mudra and conversely multiple

vaggeyakara-s can use the same mudra. Subbarama Dikshitar says ‘cevvandilinga’,

‘vijayaraghava’ were some of the mudras used by Kshetrayya other than his

favourite ‘muvvagopala’. Virabhadrayya, Ramaswamy Dikshitar all come under this

category. The mudras like ‘gopala’, ‘venkatesa’ were all favored by many

composers. The mudra ‘gopaladasa’ was used by Veena Kuppaier and his son Tiruvottriyur

Tyagayyar. The mudra ‘gopalasodari’ was used by one anonymous composers, who

works exist only in the manuscripts, seen by this author. Similarly ‘venkatesa’

was used by the composers like Annamacharya, Manambuchavadi Venkatasubbaier

etc. What can be seen here is, the mudra-s like gopala’ or ‘venkatesa’ were all

more generic, refer to the composer himself (or could be their favourite

deity), but the mudra ‘muvvgopala’ is not a generic one. It specifically refers

to the Gopala in Muvva. So, it could have been used only the composers

associated with the sthala Muvva. In that case, what was the connection between

the courtesans who has written these padam-s and the Gopala of Muvva. Muvva

(irrespective of the contestants) is certainly not in close proximity to

Tanjavur is to be noted and it is to be related with the claim that courtesans

of Nayaka era composed these padam-s. Also

we have seen, no granthakara has remarked about this mudra being used by

someone else.

Alternatively, why the courtesans in the court of

Vijayaraghava Nayaka should write padam-s, wherein the hero is Muvvagopala and

included in the daily court routine? The period of Vijayaraghava Nayaka saw the

outburst of competent courtesans, not necessarily only in the field of music.

They could have very well composed padam-s in praise of him to include it into

their repertoire and performed daily in his court. This is an intriguing question and the

scholars are compelled to give a suitable explanation, if their hypothesis is

to be accepted.

Why were the works of courtesans alone appropriated?

Throughout the article(s), we can see a statement being

reiterated multiple times in a different form – ‘works of the courtesans have

been appropriated’, though with no evidence. But, both of them didn’t even try

to look into the question ‘why their works have been appropriated’? We have a

strong rationale behind this question which will be explained now. Swarnamalya

observes:

‘For example, in the court of Raghunatha Nayaka were Ramabhadramba, Madhuravani, Krishnatvari and others.[sic] During the reign of Vijayaraghava Nayaka thrived Pasupuleti Rangajamma who wrote prolifically in eight languages alongside Krishnajamma, Candrarekha, Rupavati, Lokanayaki, Bhagyarati and others. [sic] Many of them composed padams which portrayed relationships; emotional, physical and social between the female lover and her deity / King / customer’. [sic]

This clearly shows there were many ‘female’ poets who wrote

padam-s. Pasupaleti Rangajamma has even written an opera by name “Usha

parinayamu”. This undoubtedly a love story and she was given freedom and voice

of expression to compose a dance-drama like this is to be noted. Women penning srungara pada-s were not

uncommon in our culture. Andal, one among the twelve Azvar and her works

‘Nachiyar Tirumozhi’ and ‘Tiruppavai’, serve as a good example. In the medieval

era we had the poets mentioned above and even in the colonial era, we do see

women composing works based on srungara rasa. Muddupalani and her work Radhika

Santwanamu can be cited an example for this. What we understand is, not

necessarily, a male voice is required to express srungara. More importantly,

none of the works mentioned above articulate in a male voice and none of these

works were appropriated to another poet. Contrarily, we have lot of evidences

wherein a male has written with a female voice. Those who are familiar with

Vaishnavite literature cannot forget Parankusanayaki and Parakalanayaki and

their pining for divine unison. The names might be deceiving for others; Nammazvar

and Tirumangaiazvar has composed srungara poems in the voice of a female. In

the medieval history, we have Jayadeva and in the latter period the works of

Ganam Sinayya cannot be left untouched. His padam ‘siva diksha’ clearly

explains our point. So, we only have a history of a male being voicing through

a female and not the reverse and all these works are extant till now and every

orthodox family, men or women are much aware of these poems (by Azvar and

Jayadeva).

Having understood the history properly, we have two logical

questions:

- When the works of

Andal and Muddupalani has come to us without being appropriated to a male, why the

works of courtesans alone were appropriated? They are much in line with the

above mentioned woks, wherein a lady longs to get united with her divine lover.

- Their hypothesis

looks much more ironic after reading the following statement by Swarnamalya:

‘let us not forget that Ramabhadramba, Rangajamma, Madhuravani and later Muddupalani and Nagaratnammal fall in the long line of audacious female figures from literary history, who wrote of the sensual pleasures and female sexual desires in an unabashed manner’.[sic]

She

has mentioned the female poets from the medieval and later era till

Nagarathnammal, who lived till the middle half of the last century. So, even in

the last century, we have evidences that females were bold enough to express

their views, be it sensual or non-sensual. Then why should appropriation take place?

The arrival of modern Classical dance is the reason for appropriation cannot

hold water for the reason that it was developed to its present form, only from

the second or third decade of the last century and we have a reference to Kshetrayya

from 17th/18th onwards. The first book on Kshetrayya

padam-s was published in the year 1862! Also if someone detest these lyrics in

the dance community, they would have concealed, as happened to the work Radhika

Santwanamu of Muddupalani.

Do we have a history of males writing about women-specific expression?

We do have a long cultural history in

literature. That would be beyond the scope of this article, though a few

examples has been cited elsewhere in this article.

Not all are the creations of Kshetrayya

Having

rebutted the arguments of these two scholars on the authorship of the padam-s

with the mudra ‘muvvagopala’, let us also make a record that not all the extant

compositions with the said mudras were his creations. This is particularly in response

to a query by Harshita on the padam ‘cerugu maasiyunnanu’ in the raga Begada.

It’s true, I have my period,

but don’t let that stop you.

No rules apply to another man’s wife.

I beg you to come close,

but you seem to be hesitating.

All those codes were written

by men who don’t know how to love.

When I come at you, wanting you,

why do you back off?6

It is very clear that it is much different from the other padam-s of

Ksheatrayya. There are hints to social practices that were prevalent among

Devadasis in this padam and is quite unnatural. The readers are referred to

another article, where in this author has tried to classify the composers based

on their composition. A set of composers act like social commentators – they

record the events happening around them. Purandaradasa, Samartha Ramadasa and Tyagaraja

Svamigal belongs to this category. But, excluding this (perhaps we might have

some other padam-s too), we do not find such a social commentary in his other extant

padam-s. As ably put by Pillai, Kshetrayya, being a man is always sublime even

in expressing srungara.7 A careful analysis of his padam-s will not

equip us to ignore this fact. So, this may have been a later construct and the

author of these padam-s has used Kshetrayya and his lord Muvvagopala as an

armour to make the author’s view more authentic and sounder. Let us place few

instances to support this.

Soneji refers to a javali by Neti Subbaraya Sastri ‘ceragu maseyemi’ in

the raga Kalyani.

It’s that time of the month, what can I do?

I can’t even come close to you!6

Even a

glance reveals an extraordinary similarity between the two lyrics. If we do not

know that the composer of this Kalyani javali is Subbaraya Sastri, it can be

very well mistook as a composition of Kshetrayya. Subbarama Deekshithar warns

about the tempering that have taken place to the sahitya of Kshetrayya padam-s.

Fortunately, the Kalyani javali has naupuri, purportedly to be a mudra.

Lord of Naupuri with a gentle-heart,

Don’t have these worries in your heart,6

This mudra

further raises our suspicion on the mentioned Kshetrayya padam in the ragam

Begada. This ‘naupuri’ could have been replaced as ‘muvvapuri’! We do

not argue this has taken place in this padam. What we try to reprise is the mudra of

a composer can be mutilated or rather modified to make it to appear like a

construction of another famous composer for better acceptance by the public. It is in the light of Soneji’s research, we

need to further analyze this issue. He claims this javali is not published and

the ‘kalavantulu’ whom he had interviewed sang it from her memory. Hence the

full piece was fragmented and has been pieced together by her.6 These

kind of unpublished kriti-s, especially in an oral tradition many times have a

problem with the sahitya and are much prone to interpolations.

We wish to

cite an example for this too. ‘Parakela nannu’ is a famous kriti of Syama

Sastri in the raga Kedaragaula. Whether or not sung in the concerts, it always

takes a prominent place in His Jayanthi celebrations or any tribute concerts to

him. But the sad truth is that it was not a creation of Sastri at all ! It was

actually composed by a musician by name Kakinada Krishna Iyer, who himself has

mentioned this kriti in a book published by him.8 His mudra

‘krishna’ occurs in the line ‘smaraadhinudanu sri krishnanutha’ has been

tampered as ‘smaraadhinudanu sri syama krishnanutha’ to escalate the image of

this kriti and misattributed it to Syama sastri!

When the fate of a kriti of relatively a recent construct has been changed, we

can imagine the changes that could have happened to the work of Kshetrayya

which was composed some 400 years back. The savant Subbarama Dikshitar and his wise

words does not fail to hit our mind! Alternatively his mudra in its full form

could have been used by others as happened with the case of Tyagaraja svamigal

or Muthuswamy Dikshitar.

What we wish to say is that these ‘out of the

way’ kritis could have been composed by some unknown authors and attributed to

Kshetrayya to sell their product. It is up to us to distinguish the works of

Kshetrayya from these spurious padam-s.

Conclusion

Anyone can undertake a research and give a

hypothesis. A methodical research demands truthful evidences suffixed with a

plausible explanation. Free thoughts of any author based on loose evidences is

to be condemned and cannot be accepted as a research.

We have provided evidences to prove the

existence of Kshetrayya and his association with his Lord of Muvva by composing

padam-s with the mudra ‘muvvagopala’. They are his personal interactions and it

is better to be viewed as an expression of craving to get united with the Ever-

pervading Parabrahmam.

As Swarnamlaya has stated:

‘Are we prepared to hear these padams in its original, female, liberated tone, sans the undercover of discipline, rationality, utilitarian value and knowledge of divinity?’ [sic]

It is up to an individual to view these srungara padam-s in a

female, liberated tone or in a disciplined tone to get united with the Parabrahmam,

not considering the gender at all. But it is definitely not an academically

rigorous act to make broad claims or strawman arguments, appropriating Kshetrayya’s

works and attributing them to courtesans with no clear evidence and trying to

create an impression, liberality lies only with viewing

these padam-s at a mundane level.

Also, it is essential to distinguish the padam-s of Kshetrayya

from other composers (even name of some of the composers might be an arcane).But

a deep knowledge in Telugu language along with an unbiased mindset and

disinterest in thrusting one’s idea is a pre-requisite to do this analysis.

The very main essence that Kshetrayya is a figment and his

compositions are actually that of courtesans will definitely trouble the

Devadasis, leave alone us. It is their Kshetrayya through whom they have

visualized Muvvagopala. It is their Kshetrayya who had taught them the nuances

of abhinaya through his immortal padam-s. They would be eternally witnessing

this discussion and be much happy that we have understood who He is.

Acknowledgement

I thank my friend Smt Vidya Jayaraman for helping me in

preparing this article.

References

- Harshita Mruthinti Kamath. Kshetrayya: The making of a Telugu post. The Indian Economic and Social History Review, 56(3):253-282, 2019. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0019464619852264

- Subbarāma Dīkṣitulu. Saṅgīta Sampradāya Pradarṣini. Vidyā Vilāsini Press, Eṭṭayapuraṃ Samasthānaṃ, 1904.

- Taccur Śingarācāryulu, Cinna Śankarācāryulu. Gayaka Siddhanjanam. Kalā Ratnākara, Mudrākśara Śālā, Cennapuri, 1905

- Abraham Panditar. Karunamruta Sagaram. Part 1. Tanjai Karunanidhi Vaidyasalai, 1917.

- Rajanikanta Rao, B. Makers of Indian Literature: Kshetrayya, New Delhi, 1981.

- Soneji, D. Unfinished Gestures: Devadāsīs, Memory, and Modernity in South India, Chicago, 2012.

- Manu S Pillai. https://www.thehindu.com/society/history-and-culture/the-woman-who-had-no-reason-for-shame/article24057695.ece.

- C S Krishna Iyer. Prathama Siksha Prakaranam. https://www.dropbox.com/s/ss6wf9myaqylx1u/BkTm-prathamaSikshAprakaraNam-incomplete-0222.pdf?dl=0