Apurva raga-s handled by Tyagaraja Svamigal – Svarabhusani

[simple-author-box]

Out of 600 or 700 compositions of Saint Tyāgarājā available to us, a significant fraction was composed in vinta or apūrva rāgā-s. Tyāgarājā was the first to use these rāgā-s and the source of these rāgā-s remain obscure. Saint didn’t reveal the name of these rāgā-s to his disciples. Thus, they remain a source of confusion as many kṛti-s composed in these rāgā-s has multiple lakṣaṇā-s, as transmitted by different disciple lineage. Hence, it becomes essential at least, at this point of time to collect and analyze the present available evidences, to know the lakṣaṇaṃ seen in the older versions transmitted by authentic sources. In this post, we are going to discuss few issues related to a kṛti composed in one such vinta rāgāṃ. Before going to the topic proper, a few facts are provided which are helpful in studying the kṛti-s composed in these vinta rāgā-s.

Fact 1 : Generally, rāgā-s handled by this composer can be broadly divided into three categories:

- Rāgā-s mentioned in the earlier musical treatises and popular during his time like Nāṭa

- Rāgā-s not mentioned in the earlier musical treatises but popular during his time like Begaḍa.

- Rāgā-s seen in relatively later treatises (like Saṅgīta Sarvārtha Sāraṃ, Saṅgraha Chūḍāmaṇi etc) or created by him like Kāpi nārāyaṇi.

Fact 2 : Tyāgarājā didn’t reveal the name of these apūrva rāgā-s to his disciples. This is an important fact as the name that we hear today or see today in various texts were named either by his disciples or by musicians of the gone century. 1

Fact 3 : When the composer himself has not revealed the name of these rāgā-s , it is illogical to say that Tyāgarājā has composed in the rāgā-s seen in the treatise Saṅgraha Chūḍāmaṇi of Gōvinda. This point will be emphasized in future posts too.

Fact 4 : The main difference between the earlier musical treatises (treatises composed till Sangīta Sārāmṛtā, dated approximately to 1735, like Sangīta Sudhā , Catuṛdanḍi Prakāśika etc) and the later ones (like Saṅgīta Sarvārtha Sāraṃ (SSS), Saṅgraha Chūḍāmaṇi (SC) etc) lies in the way in which a particular rāgā was handled. Whereas in the former treatises, each rāgā was explained by the phrases they take, latter treatises explain by giving a scale – ārohaṇa and avarōhaṇa. In some, we find a lakśaṇa gītaṃ. Hence, a rāgaṃ is visualized as an synthetic entity which strictly obeys its scale by the proponents of the later treatises; whereas the proponents of the earlier treatises view these rāgā-s as an organic structure which cannot be explained by a scale always.

Fact 5 : Rāgā-s that we come to know by SSS and/or SC is not a complete list; they are just a sample. We have got many manuscripts preserved carefully in various libraries waiting to confuse us. The point that this author tries to establish by quoting this point is, a rāgā can have multiple scales, depending on the author who writes the treatise. A rāgā which is placed under a particular mēḷā could have been placed under a different mēḷā by a different author. Also, a rāgā with a similar set of svarā-s could have been called by a different name by various authors.

Fact 6 : Unless, we see the notation, it is not advisable to get carried away by the rāgā name alone (see Fact 5).

With this basic understanding, we shall move to the post “Varadaraja ninnu kori”.

This is a relatively rare kṛti composed on the Lord Varadarājā of Kāñcipuram. This is believed to have been composed by the Saint during his sojourn to holy places like Kāñcipuram, Tirupati etc. Much about this composition has been mentioned in another relevant article in this site. This article will focus on the history of this rāgaṃ with a special emphasis on Vālājāpet notations.

Svarabhūṣaṇi in treatises and texts

Svarabhūṣaṇi belongs to the third category in the classification mentioned above. Strangely, it is not mentioned in SSS or SC. Hence, it must be in some treatise which is yet to be discovered or it can be a creation of the Saint itself.

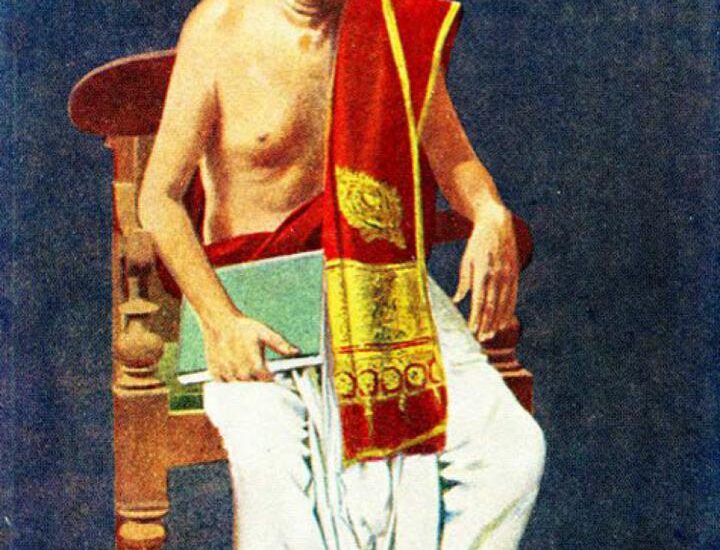

It is one kṛti of the Saint which is not frequently seen in the texts published in the last century. First text to link the rāgaṃ with this kṛti is “Oriental Music in European Notation”, published by Sri AM Chinnasvāmy Mudaliyār (AMC) in 18932 (see figure 1) . He tried to collect and record the authentic versions and kṛti-s of Tyāgarājā and hence approached one of his direct disciple, Vālājāpet Kṛṣṇasvāmy Bhāgavatar (VKB). His versions were cross checked with other disciples of the Saint and what we see today is the version approved by more than musician excluding VKB. Though, this kṛti is not notated here, we clearly see for the first time, the rāgā for this kṛti is mentioned as Svarabhūsaṇi, a janya of mēḷā 22. Later this rāgaṃ placed under mēḷa 22 can be seen in various texts including Nathamuni Panḍitar’s Saṅgīta Svara Prastāra Sāgaraṃ published in 1914.

It is to be pointed here we are really clueless on who named this rāgaṃ as it is not seen in any treatises that are presently available to us. But, it can be safely said that the rāgaṃ of this composition is a janyam of mēḷā 22 and is much different from its allied rāga Dēvamanōhari. The musicians who worked with AMC and AMC were well aware of Dēvamanōhari. Listing of few kṛti-s of the Saint under Dēvamanōhari and notating a composition of Gōpāla Krṣṇa Bhārati in Dēvamanōhari in the same book proves the same.

From what we have seen till now, it can be summarized Tyāgarājā has not revealed the name of any of the apūrva rāgā used by him. Some unknown musician has named it as Svarabhūṣani. AMC, who was in search of the authentic compositions and versions of the Saint, accepted this as such.

Svarabhūṣaṇi and Varadarāja ninnu kori in manuscripts

Though, efforts have been made from late 1800s to record our music in the form of printed texts, several material remain unknown in manuscripts and they exist as a private collection. A study of these manuscripts is a must as they give a broader picture of the issue in hand.

It is quite rare to find this kṛti in manuscripts too. This shows that this kṛti was not learnt by many disciples and this should have been in the repertoire of only very few. Vālājāpet Vēṅkaṭaramaṇa Bhāgavatar was one amongst them to learn this directly from the Saint.

Let us now see few manuscripts which make a mention about this kṛti.

Manuscript 1

Dr V Rāghavan, in a paper published in the Journal of Music Academy mentioned about the discrepancies in allotting a particular rāgā name to a particular kṛti (of Tyāgarājā). He has presented a paper based on a palm leaf manuscript which he had in his possession. This kṛti find its presence there and the rāgā of this kṛti is mentioned as Śāradhābharaṇaṃ, a janya of mēḷa 34, Vāgadhīṣvari. We are totally unaware of the musical structure as notation was not provided in the paper. 3

Manuscript 2

A manuscript by one Bālasubraḥmaṇya Ayyar, written in the year 1922 says the rāgaṃ of this kṛti as Svarabhūṣaṇi. Notation is provided.

Manuscript 3

A granta manuscript in the collection of Late, Srivanchiyam Sri Ramachandra Ayyar says the rāgaṃ of this kṛti as Śāradhābharaṇaṃ. Again, notation is not provided.

Manuscript 4

A manuscript written by Vīṇa Kuppaier mentions this kṛti. Unfortunately, rāgā name was not mentioned and notation too was not provided.

Manuscript 5

Vālājāpet notations mention as Svarabhūṣani.

From the study of manuscripts, it becomes clear that there was confusion in the rāgā of this kṛti. Two different sources saying the rāgā as Śāradhābharaṇaṃ is an issue to ponder. Also, two different sources ascribing this kṛti to Svarabhūṣaṇi also validates the musical structure, where in the rāgā takes the svarā-s of mēḷa 22. Unless, we get a manuscript or text which gives the version in Śāradhābharaṇaṃ, we cannot come to a conclusion that Śāradhābharaṇaṃ and Svarabhūṣaṇi are two different versions (See fact 4).

Svarabhūṣaṇi – its scale

To the best knowledge of this author, Saṅgīta Candrikai of Māṇikka Mudaliyār, published in the year 1902 is the first printed text to mention the scale of this rāgaṃ as SGMPDNS SNDPMRS, placing it under the mēḷa 22. The two manuscripts mentioned above (manuscript 2 and 5) give the same scale. Vālājāpet notations give additional information that this takes the notes of Kharaharapriya.

Earlier texts and manuscripts are uniform in their opinion that this is a janyaṃ of Kharaharapriya and the scale can be taken as SGMPDNS SNDPMRS.

Varadarāja ninnu kōri – Vālājāpet version

Vālājāpet manuscripts form an important source to understand the kṛti-s of Saint Tyāgarājā. These manuscripts were written by Vālājāpet Vēṅkaṭaramaṇa Bhāgavatar (VVB) and his son Vālājāpet Kṛṣṇasvāmy Bhāgavatar. It is even said Tyāgarājā could have seen this as they were recorded during his life time.4 These notations were preserved at Madurai Sourāṣtra Sabha and the transcripts are available in GOML, Chennai. Few of these transcripts can be accessed online here. These transcripts are the main source for this post.

In the absence of first hand records made by Tyāgarājā, these notations form a very valuable and authentic source to understand the version learnt by his prime disciple Vēṅkaṭaramaṇa Bhāgavatar.

In the notations, it is mentioned as Svarabhūṣaṇi with the scale SGMPDNS SNDPMRS. This scale is much adhered to in the version given.

Pallavi starts from dhaivataṃ, reaches madhya ṣaḍjaṃ and goes to gāndhāraṃ as DPMRSGMP. This clearly shows the rāga lakshaṇaṃ without any ambiguity. Anupallavi again starts from dhaivataṃ, but here proceed upwards and reaches tāra ṣaḍjaṃ. From here again reaches tāra gāndhāraṃ. The intelligent use of dhaivataṃ as a graha svaram and careful emphasis on the scale gives a melodic structure much different from Dēvamanōhari. Nowhere we find the phrase NDNS in this version. It is only DNS.

Caraṇaṃ has something interesting to say. It has got an additional line “maruḍu śiggu chē manḍarāḍaṭa”.

This is not seen in any of the versions recorded – either oral or textual. Interestingly, this additional line is seen in the manuscripts of Vīṇa Kuppaier!! Knowing the association between VVB and Vīṇa Kuppaier, this line adds authenticity to this version.

But, in the manuscripts of Vīṇa Kuppaier, there is a slight change in the sāhityaṃ. It reads as “maruḍu śiggu chē munḍararāḍaṭa”. This was the correction mentioned by Ravi too (See another article on this topic in this site).

Errors like this where there is a replacement of one syllable to another is much common in manuscripts. They are not the printed texts which are proof-read several times before publication (even they are prone to errors!!) What we see now, the transcripts are the genuine duplicates of the manuscripts preserved at Madurai Sabhā. The scribe, when trying to duplicate the contents from manuscripts could have made this error involuntarily. In this case, except that syllable, absolute concordance is seen between the two manuscripts under consideration. An unbiased researcher who is accustomed in reading the manuscripts will never judge the authenticity of the composition or the source which gives this composition based on the errors of this magnitude.

Let us now see the importance of this additional line. Caraṇaṃ with the additional line is represented below:

varagiri vaikuṇṭha maṭa varṇiṃpa taramukāḍaṭa

maruḍu śiggu chē man ḍarāḍaṭa – nir (munḍararāḍaṭa)

-jarulanu tārakamulalō candrudai merayuḍu vaṭa

vara tyāgarāja nuta garuḍa sēva jūḍa srī

‘Ra’ is used as dvitīyākśara prāsaṃ in this caraṇaṃ. When it is sung in rūpaka tāḷaṃ (catusra rūpakaṃ), each tāḷa cycle ends with maṭa, dhaṭa, man, nir, mulalō, vaṭa, nuta and juḍa. Hence each āvartanaṃ starts with a word which has ‘ra´ as its second syllable. Totally, we get 8 tāḷa āvartanaṃ only due to the presence of this additional line. In the commonly heard versions, if sung in rūpakaṃ, runs only for 6 āvartanaṃ!! Also, ‘nir’ is pushed to previous āvartanam to be in accordance with the rules of prosody.

Hence, this line must have been an integral part of this kṛti known only to the disciples learnt directly from the composer and singing without this line is an aberration.

Here is the link to Vālājāpet version of this kṛti.

A note on the version by Sri Bālasubraḥmaṇya Ayyar

No detail can be collected about this musician. The version given by him is much in line with the version that we hear starting in tāra saḍjaṃ, though differences exist. A ciṭṭa svara passage is too seen. Additional line seen in the two manuscripts mentioned above is missing. This version too does not sound like Dēvamanōhari. Needless to say, the version given here is much different from that of Vālājāpet version.

Conclusion

The following are “take-home” messages from this post:

Our music is transmitted very well through both textual and oral tradition. In the absence of one, the other is to be taken into consideration. A wise researcher will never neglect an evidence gained through one source when the other one is unaware of the same. Oral renditions and the available texts are only samples to show what was sung in he past. Voice of many musicians were not recorded and the knowledge of many researchers remain unpublished. If we get an additional evidence from unpublished source, that should be analysed and digested. This an only be considered as a true research. In this case, Valajapet versions were in the dark for many years. When the notations adhere well to the scale, it should be accepted as an old version. This will be explained more in further posts too.

“Varadarāja ninnu kōri” was composed in a rāgaṃ which takes the svarā-s of mēḷa 22. (till we get an evidence from other authentic source saying it as Śāradhābharaṇaṃ or something else).

It is better to call this rāgaṃ as Svarabhūṣaṇi as it is the name seen in one of the earlier texts published (as gleaned from the available evidence) and no other rāgaṃ exist with that name.

We don’t have any textual tradition to call it as Dēvamanōhari. Even oral traditions call it as Svarabhūṣaṇi, though versions differ. Older version like Vālājāpet notations gives us the real lakṣaṇaṃ of a rāgaṃ like this. Svarabhūṣani had a distinct melody which can be best experienced by listening to Vālājāpet version.

The additional line, seen in Vālājāpet version and manuscript of Vīṇa Kuppaier is integral to this composition. That line is to be included to make this kṛti a complete one.

Vālājāpet notations help us to know about the authentic versions learnt by VVB, directly from the Saint and solve many issues pertaining to the rāga lakṣaṇaṃ of vinta rāgā-s like this.

This example also highlights the importance of collecting and analyzing unpublished manuscripts to understand the rāgā-s handled by the Saint.

Acknowledgements

I like to thank Sri V Sriram, Secretary, Music Academy for allowing me to peruse the manuscript of Sri Balasubrahmanya Ayyar preserved at Music Academy library.

I thank Srivanchiyam Sri Chandrasekar, son of Srivanchiyam Sri Ramachandra Ayyar for sharing the rare manuscripts collected and preserved by his father.

I thank Sri Ravi Rajagopal for taking efforts to correct the error in sāhityam seen in the additional line .

References

- Subbarāma Dīkṣitulu. Prathamābhyāsa Pustakamu, Pg 129. Vidyā Vilāsini Press, Eṭṭayapuraṃ Subbarāma Samasthānaṃ, 1905.

- Chinnasvāmy Mudaliyār. Oriental Music in European Notation. Ave Maria Press, Madras,1893.

- Raghavan V. Two manuscript of Tyagaraja Songs. Journal of Music Academy. 1947: Pg 142.

- Sāmbamurti P. The Walajapet manuscripts. Journal of Music Academy. 1947: Pg 114-129.

Excellent study of the background of Svarabhushani.

Thank you sir.

Wonderful

Thank you!!