[simple-author-box]

INTRODUCTION:

We did see the detailed analysis of Narayanagaula in our earlier blog post. Now in this short blog post we shall see a few more aspects of this raga including a comparative study with some allied ragas along with a note on Kuppayyar’s beautiful kriti which is never at seen in the concert circuit.

Read on!

COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS – SUMMARY:

There is considerable melodic relationship between Narayanagaula and the following set of ragas:

- Kedaragaula

- Surati

- Kapinarayani

While the first two have considerable music history backing them, the last raga Kapi Narayani is a eka kriti raga the creation of which is attributed to Tyagaraja. Given the common svaras and murcchanas which form the single body for these ragas/melodies, one needs to get down to the musical analysis using the notes and the motifs and jiva, nyasa and graha svaras on one hand and the practical musical exposition of the ragas on the other.

Let’s first look at the comparative chart of these ragas as above. The chart below is prepared with Narayanagaula as focus raga and how it contrasts from its siblings.

| Raga | Nominal arohana | Nominal avarohana |

| Kedaragaula | S R M P N S | S N D P M G R S |

| Surati | S R M P N S | S N D P M G R S |

| Narayanagaula | S R M P N D N S | S N D P M G R G R S |

| Kapi Narayani | S R M P D N S | S N D P M G R G R S |

| Narayanagaula | Kapi Narayani | Kedaragaula | Surati | |

| Key aroha phrases | SRMPNNS ;SRMPNDNS ;Ghana raga; tristayi raga | SRMPDNS | PNDNS not seen ; rakti raga; tristhayi raga | SNDNS & NDNS are seen; No movement below mandara Nishada |

| Distinctive avarohana krama combinations | SNDPMGRGRS ;SNDMPMGRGRS | SNDPMGRG.R.. | SNDPMGRS | SNDPMGPMRS ; SNDPMGRS |

| Distinctive murcchanas | PDM and PNDM; G.RGR. is seen while MRS does not occur. Again MGS is used; MGRGR is a patented murccana for this raga & is to be avoided in allied ragas | MG..RGr… with a marked emphasis on the G and R & r as a repeated nyasa marks this raga | MGS is never used; Use of MGMPR is distinctive of Surati. | |

| Weak notes | Gandhara is an extremely strong note. Dhaivata is an accepted graha svara as well. Gandhara falls to sadharana value in some phrases ( nGRS) | G2 is not seen. Emphasis is always on the nyasa note rishabha. | True to its rAgAngA status, it cannot be tinted with G2 at all. | Gandhara & dhaivata are very weak notes & is never a graha or nyasa. Gandhara is very close to madhyama as if it were a simple place holder svara and similarly dhaivata is close to nishada. |

| Strong notes | Ni and Ma are very strong and are preferred graha svaras /starting notes. Always begin murcchanas with them and end them/nyasa svara with Ri. | Given PDNS as a complete uttaranga, all these notes are powerful graha/nyasa notes. | Ni is the graha svara | Ni is a strong note and is a preferred jiva svara; Sadja is the graha svara |

| Melodic structuring | Jhanta notes to be favoured ; sA or pA to be avoided as resting notes. In an exposition of the raga always place the pivot of the raga on the graha/jiva notes and start on the graha and end on the preferred nyasa note. | Jhanta notes to be favoured. | Sa and Pa are preferred resting notes. | Ri is a preferred resting note was well while sa and pa preferred graha svaras apart from Nishada . PMR, NDPPMR and MGMPR , is used profusely. |

An excellent svara gnanam/musical competence and practiced experience is needed to perform manodharma/Kalpana sangitam in this raga. It is certainly not a raga for the faint-hearted. It cannot be sung with traces of Kedaragaula or Surati. It demands intimate knowledge of rendering the unique micro tones of nishadha and madhyama, usage of appropriate start and ending notes, emphasis on janta notes and ability to sing the raga in the first kalam/speed. The renditional complexity of the raga increases as under:

Plain Kriti ->plain varnam -> svara Kalpana in second speed -> svara Kalpana in first speed – > tanam –> alapana -> neraval

Kedaragaula, Narayanagaula and Surati can never be understood and distinguished just on the basis of grammar or svaras. A student who has not heard these ragas can never sing them true to form from notation. Only by hearing the practical exposition of these ragas by great masters can one really be able to understand the notation, as well as the melodic contours and the distinguishing features of these ragas.

A NOTE ON ‘NANNU BROCEVAREVVARE’ of KUPPAYYAR:

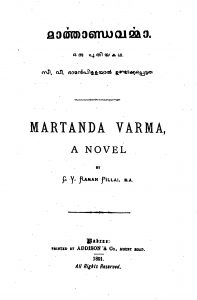

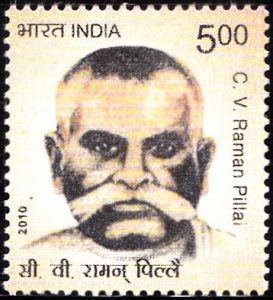

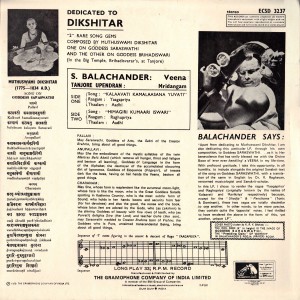

A common theme underlying the practical exposition of these ragas is the telling use of individual notes as a graha or nyasa, emphasizing the jiva and dhirga svaras and the leitmotifs in the svara prastara. These are the keys to present a proper picture of these ragas distinctly. The exemplars for Narayanagaula has been shared in the earlier blog post covering the Varna, kriti and a couple of svara Kalpana clippings. The Narayangaula kriti of Veena Kuppayyar was mentioned in passing in my previous post but I would like to present a personal rendering of the same. Given the fact that the composition is never ever rendered plus the fact that the composer specialized in the raga, intrigued me so so much that I learnt it from notation with the raga knowledge gained from Dikshitar’s ‘Sri ramam’ and the Kuppayyar varna. Any errors or omission is entirely due to my amateurish knowledge/presentation.

A few points merit our attention in the architecture of this composition:

- Much like Dikshitar, Kuppayyar gives pride of place to Dha. He starts the anupallavi with Dha, like the anupallavi take off at ‘dhIrAgraganyam’ in Sriramam.

- The anupallavi is decorated with a sprightly cittasvara section while the carana loops back to the pallavi through a crowning madhayama kala sahitya section a la Dikshitar!

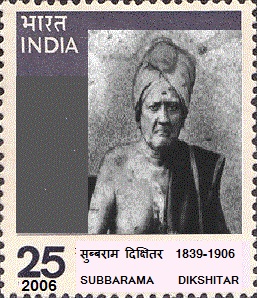

- MGRGRS, the leitmotif occurs aplenty in the composition. It occurs 2 times in the pallavi, 3 times in the anupallavi and 9 times in the carana excluding the cittasvara section. A staggering 14 total occurrences with at least one for every tala avarta! So much for this leitmotif. He also uses DMP deliberately as well. One is forced recollect the intervention of Gayakasikhamani Harikesanallur Muthiah Bagavathar during the Experts Committee meeting of the Music Academy when it met to deliberate on this raga’s lakshana, which I have summarized elsewhere in this blog post. He wanted DMP to enshrined in the avarohana murrcana which will distinguish it from Kedaragaula beyond doubt. He wanted it to be SNDMPMGRGRS, so much for the veteran’s formidable lakshya and lakshana gnana! The same is recorded in JMA 1935-37 pp156-157. The Experts Committee unsurprisingly without much ado concluded that SRMPNDNS and SNDPMGRGRS as the arohana and avarohana krama on 31st December 1934. They too agreed that MGRGRS was a lietmotif to be used and enshrined it as a part of the avarohana.

- In sum this kriti encompasses the set of all permissible murccanas which distinctively form the basis of the lakshana of Narayangaula – SRMP ; MPNNS ; MPNDNS ; Nsrmgrgrs; NNDPMP ; NDMP; PMNNDP; MGRGRS ; MGS; nndpnnsS ( the svaras in normal upper case are mandhara stayi svaras; lower case are tAra stAyI and lower case italics are mandhara stayi svaras.

DISCOGRAPHY OF ALLIED RAGAS:

Covered next is a set of curated renderings of Surati, Kapi Narayani and Kedaragaula as svarakalpana or as viruttam singing as they offer the most in terms of understanding raga architecture.

First of the lot is Surati and presented herein is the improvisation as a part of the pallavi ragamalika by Vidvan T M Krishna, from a concert in the public domain.

The rendering is a part of the pallavi in the raga Janaranjani with its sahitya being the pallavi portion of Maha Vaidyanatha Iyer’s composition ‘ Pahimam Sri Rajarajesvari krupAkari sankari’. Attention is invited at the unique nishadha svara with which the vidvan invokes the imagery of Surati for us.

Presented next is the svara kalpana rendering of Sangita Kalanidhi Semmangudi Srinivasa Iyer for the classic Veenai Kuppayyar adi tala tana varnam in Surati, ‘entO prEma’. We pick up action at the beginning of the last ettugada svara section for the caranam line ‘panta mEla jEsEvu IvEla’ . The veteran almost concludes the piece with the last avarta with the mrudangist too playing the concluding stroke even as Sri Srinivasa Iyer changes his mind at the very last moment and launches his sarva laghu svaraprastara. The way the legendary Sri Lalgudi Jayaraman follows the maestro like a devoted slave, as somebody put it, is a treat.

As one an see the raga blossoms forth in the uttarAngA around nishada svara and in the pUrvAngA of the top octave.

Surati is always included as a part of the suite of ragas in viruttam singing at the fag end of any concert, tailing into the mangalam. The legendary doyenne Sangita Kalanidhi Smt T Brinda takes a beautiful anonymous Sanskrit sloka, ‘vihAya kamalAlaya’ and strings the verses in a garland of ragas including Purvikalyani, Sahana, Behag, Kanada, Surati and finally Madhyamavathi. I am presenting the entire rendering of her’s for the simple reason that it is wholesome and she packages all our crown jewels that our music can offer, in less than 10 minutes.

Here is the text of the sloka for those of us who may be interested.

vihAya kamalAlayA vilasitAni vidyunnaTI

viDambana paTUni mE viharaNam vidhattAm manaH |

kapardini kumudvatI ramaNa khaNDa cUDAmaNau

kaTI taTa paTI bhavat-karaTicarmaNi brahmaNi ||

Hark at how ravishingly she packs the entire essence of Surati within a minute. She starts Surati at 7:26 into this clip, distilling all that perfume of the East in a minute and rapidly transitioning into its close cousin Madhyamavati. A veritable lesson for a student of music in elaborating a raga in a sloka/viruttham.

For Kapi Narayani , Tyagaraja’s sole exemplar kriti ‘Sarasamadhana’ has been made his own by the great vocalist Ganakaladhara Madurai Mani Iyer. His inimitable rendering of the composition, his copious mandharma in his execution of the neraval and sarvalaghu svarakalpana littered with janta prayogas on the carana line, ‘hitavumAta’ gives goose bumps, to a listener even to this date, decades after his passing away. In his recording which is available in the public domain, Mani Iyer uses the dhaivatha note as a graha and nyasa note for his imaginative svaraprastara. For our understanding, I present the rendering of contemporary performer, Vidushi Amrutha Murali. The Vidusi in the company of her guru, Vidvan R K Sriramkumar and mrudangist Arun Prakash leverages the nishadha note instead as her pivot/anchor svara for her svara kalpana sorties. As pointed out earlier Narayanagaula has a vakra uttaranga PNDNS while Kapi Narayani has a lineal PDNS as its uttaranga. The clipping commences with her neraval on the caranam line ‘hitavUmAta’. Did the raga Narayangaula give Tyagaraja the inspiration to sculpt this noveau raga Kapinarayani, a raga without a textual history ? We do not know.

We move on finally to Kedaragaula, a raganga raga of yore. The readers are invited to hear out the versions of Kedaragaula which is available in abundance in the public as well commercial domain. But personally nothing beats the beautifully encapsulated pristine, classical Kedaragaula by Smt K B Sundarambal from a Tamil film of yester years. She starts her viruttam in Mohanam, moves on to Kedaragaula and finally on to Kanada. Hear her dwell on Kedaragaula starting at 0.28.

In this clip, the veteran stage singer famed for her majestic voice spanning 3 full octaves, open throat singing and impeccable purity of sruti paints a perfect Kedargaula fit for a novice and the cognoscenti, in the same breath. For me it is much like how Prof SRJ waxes eloquent on the beauty of M K Tyagaraja Bagavathar’s rendering of ‘Siva peruman krupai vendum” in Surati ( at 9:47 in the clipping) which was alluded to in an early blog post.

As the respected Professor points out, by extension just on the gandhara and dhaivata the distinction between the the three ragas Surati, Kedaragaula and Narayanagaula can be brought out in conjunction with the graha/nyasa svaras.

CONCLUSION:

In sum Narayanagaula is not a raga for novices or for the faint hearted. It demands an in-depth or intimate if not extraordinary knowledge of the raga on the part of a performer, given the melodic overlap it has with its neighbouring ragas, which share the same melodic material.

We always like some sort of an apocryphal/sensational/spicy story or two about melodies or musical personages. And chroniclers both present and past seem to have a predilection for exaggerating the facts or events as they go about recording them during their lifetimes. I end this rumination blog post with one such story/event, probably true, about how the vocalist nonpareil Maha Vaidyanatha Iyer (1844-1893) used this raga Narayanagaula to stump his opponent in a musical contest. True or untrue, the raga becomes the pivot of the story which is recorded for posterity by Vidvan Gomathisankara Iyer ( “Isai Vallunargal” published in 1970) as told to him by his musician father Pallavi Subbiah Bhagavathar, who was a disciple of Maha Vaidyanatha Iyer being his pupil between the years 1876-1882. In his almost panegyric narration, Vidvan Gomathi Sankara Iyer provides all the elements of suspense and intrigue.

In the late 1880’s, Maha Vaidyanatha Iyer was on an extended stay at Madras on a musical sojourn enjoying his popularity, the adulation and patronage extended by the denizens of the city and the of the officials of the administration including the Governor of Madras. A special dinner was hosted in his honor by the Governor Robert Bourke known more by his peerage name of Baron/Lord Connemara along with his wife Baroness/Lady Connemara. Post the dinner, the invited celebrities were treated with a sumptuous concert by the legend, who apparently even sang English notes for the benefit of the assembled English speaking glitterati. Perhaps they must have been the nottusvara sahityas of Muthusvami Dikshitar !

This public display of adulation for Maha Vaidyanatha Iyer did not fail to make a few of the vidvans envious or jealous, for so popular and sought after he was that many thought, never mind if music emanated or not, thousands would gather at the mere move of his mouth! Vidvan Venugopal Das Naidu, a vocalist of not so well known provenance and a citizen of the City, was one of those who viewed the entire spectacle with envy. A man who prided himself by decking in a royal demeanour, Venu as he was endearing called vented his fury to his violinist friend ‘Photograph” Masilamani Mudaliar. His opinion was to the effect that “Maha” was a fake appellation which Vaidyanatha Iyer did not at all deserve and he was simply putting up a charade without an ounce of practical musical worth. According to Subbiah Bagavathar, Venu and Mudaliar acting “in concert” so as to put it, decided that forthwith Maha Vaidyanatha Iyer should be challenged for a contest and went public with that. In pursuance to that, a fund raising spree was launched, mopping up a princely sum of more than Rs. 2000/, which was to defray the cost of a huge silver salve and gold ear studs which the winner would eventually take. Notices were printed and distributed as advertisement, fixing the terms of the concert, unilaterally, virtually rigging up the entire contest. Thus the duo put it out that the residence of Fiddle Ramayya Pillai, a wealthy musician of George Town would be the venue, Maha Vaidyanatha Iyer would be given the first opportunity to sing first, choosing the raga of the Pallavi and elaborating it. Venugopal Naidu will then sing a Pallavi in that raga following which Vaidyanatha Iyer would have to elaborate it. If he could not he would have to relinquish his title in public. The duo set the rules of the game, the time, date and venue as well to their advantage apparently and threw the gauntlet at the great vocalist.

The stratagem was not too complicated. Given that pallavis were traditionally sung in the heavy ragas namely Bhairavi, Kambhoji, Sankarabharanam or Kalyani, the idea was to entrap Maha Vaidyanatha Iyer with Venu setting the Pallavi in a complicated rhythmic setting, without openly putting the tala so that it would stump the veteran vocalist. As if to result-proof this contest even further, Masilamani Mudaliyar himself was anointed as the arbiter/referee of this contest!

When Maha Vaidyanatha Iyer and his elder brother Ramasvami Sivan, who was his alter ego and accompanying junior partner/vocalist in his concerts, heard of the challenge, they grew extremely uncomfortable. Subbiah Bagavathar’s version has it that Vaidyanatha Iyer’s ardent & leading rasikas/admirers would have none of it and they goaded Vaidyanatha Iyer into accepting the challenge.

On the appointed day and time at the venue in George Town, rasikas agog with excitement had assembled to watch the proceedings with bated breath. With Masilamani Mudaliar as referee the proceedings commenced in right earnest and in deference to protocol, Vaidyanatha Iyer asked Venu his challenger if he had any raga as his preference for the Pallavi exposition. We do not have any evidence if there was any premeditated strategy on tackling the situation on his part. On Vaidyanatha Iyer’s seemingly innocuous question, Venugopal Naidu perhaps haughtily, responded “Any raga of your choice”. Vaidyanatha Iyer in line with the prevailing practice had planned to sing the Pallavi in Sankarabharanam and he prepared himself to do so. Perhaps as fortune would have it, a brainwave struck Ramasvami Sivan who was sitting behind next to his brother, strumming the tanpura perhaps. In a trice he leaned forward and whispered into Vaidyanatha Iyer’s ears to junk the plan to sing the Pallavi in Sankarabharanam. He proceeded to suggest Narayanagaula as the raga of the Pallavi and he said so in their secret coded language (pAnDava bAshA is the name, Pallavi Subbiah Bagavathar gives for that coded language that was used by the brothers), lest it may be over heard & understood by Venu. Apparently the rarity of the raga and the equally rare practice perhaps to use it as a vehicle of Pallavi exposition was the plan that what Ramasvami Sivan had to win this contest, hands down. Gomathi Sankara Iyer records further that the raga Narayanagaula with its vakra sancaras or its “turn of notes” makes it difficult for manipulation in a Pallavi and this proved to be a master stroke! As the great titan held in awe by his contemporaries, began humming (Vaidyanatha Iyer had a ‘hUmkAra way of raga elaboration) the raga and began his exposition, a cloud of silence descended on the venue. The unique and and not so frequently heard raga coming forth from the vocal chords of the Prince Charming of Music of those days, cast a spell on the crowd.

One can easily envision Vaidyanatha Iyer performing his alapana in a grand and eloquent manner, for Soolamangalam Vaidyanatha Bagavathar and Dr U Ve Svaminatha Iyer in their respective memoirs, provide that vivid picture of Vaidyanatha Iyer’s inimitable way of singing. Subbiah Bagavathar records that on that day, Vaidyanatha Iyer had performed a complete alapana of Narayanagaula for about 45 minutes perhaps spanning the three octaves he was known for. Needless to add it must have been a veritable feast for the celestials.

The narration goes on to say that not surprisingly, Venu had no clue as to the raga. So bedevilled and muddled he was that even as Iyer was immersed in his exposition, he retired from the stage to a quiet corner to re-plan by retrofitting his preplanned pallavi to the melody that he was hearing, without any success. By then Vaidyanatha Iyer had finished his tour-de force alapana and perhaps the tanam as well and Venu was nowhere to be seen. It must have been a great tanam, par excellence, as the raga is so amenable to madhyama kala exposition for which Vaidyanatha Iyer was justly famous for during his heydays. And with the challenger Venu who went missing from the stage, not seen at all, the referee Masilamani Mudaliar grudgingly requested Vaidyanatha Iyer to complete the rendering with his own Pallavi which the veteran did as if like a fish taking to water. The final Pallavi rendition must have been a proverbial icing on the cake for the assembled cognoscenti of Chennapattana. And not surprisingly at the end of the performance, Vaidyanatha Iyer was felicitated and presented with the prize money and gifts.

Thus ends the story of Vaidyanatha Iyer leveraging this great raga Narayanagaula to defend his title ‘Maha’ conferred on him by the Pontiff of the Siva Mutt at Tiruvavaduthurai, decades prior. Needless to add, he returned home adding one more exotic event to his already legendary reputation and also richer by the gifts bestowed on him. So much for the raga Narayanagaula!