[simple-author-box]

Introduction:

History is littered with instances of many Kings falling from grace due to political bickering, back room or royal intrigues, machinations of foreign powers or neighboring Kingdoms, outright misrule bringing about a palace coup or public revolt and the like. The period of 1765 to 1800 in the case of Tanjore regionlikewise was a period of great political turmoil and polarization. Apart from the native rulers of the area which included the Maratta clan of Tanjore, the Nawab of Arcot and the smaller fiefdoms of Udayarpalayam and others, the dramatis personae also included Hyder Ali and his son Tipu Sultan from Mysore. Pitching these rulers one against the other, in the game of elimination were the two foreign powers namely France and England. The British East India Company was attempting to consolidate its hold through its Governor at Madras Fort St, Sir George Pigot while the French were trying to be one up with their Governor in Pondicherry the famous Dupleix providing the stewardship.

Amidst all this war and political turmoil, Art was patronized and it grew to its zenith. Kings & Chieftains played patrons to the hilt even while as they involved themselves in wars and in cunning machinations to stay in power. For many of us, Tanjore and hence that Maharatta rule of Tanjore is synonymous with King Sarabhoji whose regnal years were 1799 to 1832 ( see foot note 1) .

This blog post is about his predecessor, King Amarasimha or Ramaswami Amarasimha Bhonsle ( the full Royal titular name) who ruled for a brief period of 1787 to 1799 as a Regent of the minor Prince Sarabhoji. This King Amarsimha was a patron in his own right like many of his illustrious kinsmen who ruled before him, right from King Sahaji who was a composer & musicologist (author of Ragalakshanamu), King Tulaja I who is tagged with the authorship of the Saramruta and Pratapasimha who was a great patron of arts & music and who was called as Abhinava Bhoja. Amarasimha too was a patron of many musicians including Ramasvami Dikshitar the father of the Trinitarian Muthusvami Dikshitar. Amarasimha is referred to as Amar Sing(h) as well in very many documents and also as Madhyarjunam Amarasimha, for later in his life he was banished to live in exile at Madhyarjunam / Tiruvidaimarudur, a few miles from Kumbakonam. This blog is about this King Amarasimha ( always referred to as is) & his times and from a musical angle we will see an exemplar composition sung on him by Ramaswami Dikshitar. This piece is a ragamalika documented in the Sangita Sampradaya Pradarshini (SSP hereafter) of Subbarama Dikshitar and from a performance perspective it is extinct for all practical purposes. As pointed out in an earlier blog post in this series , the overall enjoyment of a composition is enhanced by knowing about the historical background, the setting, the composer’s perspective and such other factors like the nayaka of the song etc. . Hence the profile of the patron King Amarasimha, the context of the composition – time, place etc. and the composition ‘sAmajagamana’ along with the discography is sought to be presented.

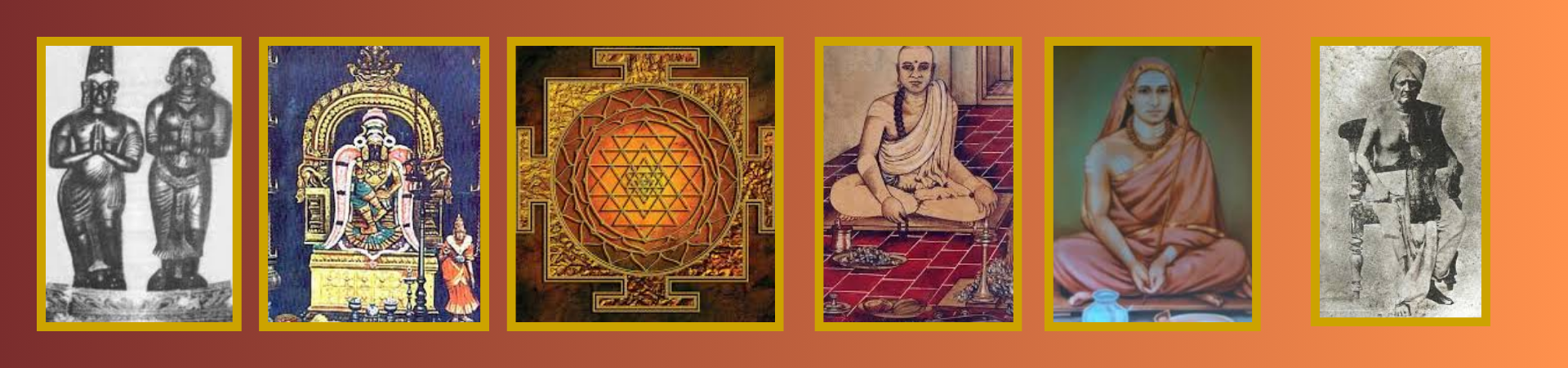

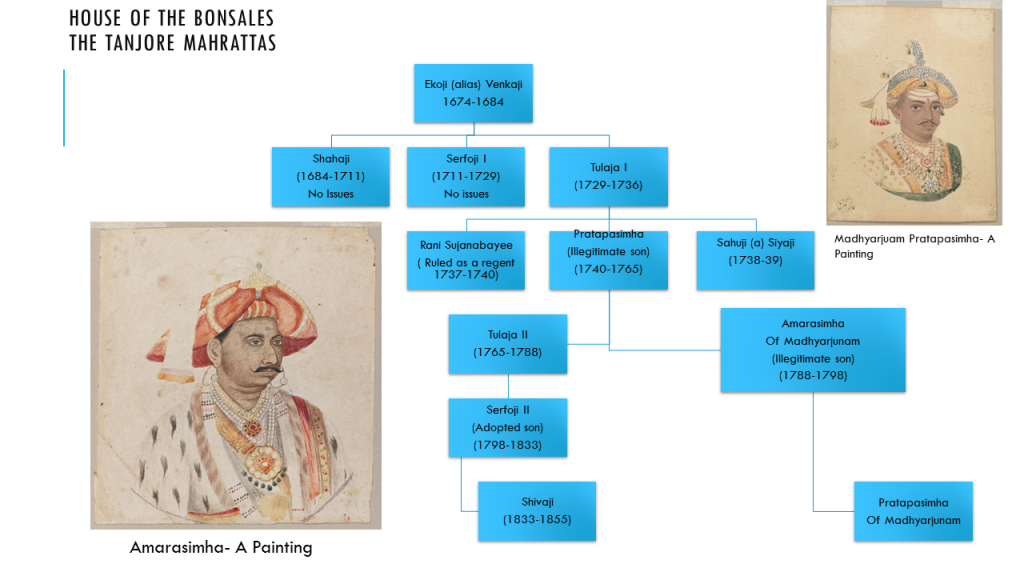

THE ROYAL HOUSE OF BHONSALES- The TANJORE MAHARATTAS:

The Mahratta rule of Tanjore commenced in the year 1675 (from the remains of the erstwhile Nayak rule). The lineage of Kings who ruled from Tanjore from this Royal House is given in the genealogy chart below. They were apart o the extended Bhonsale clan of Maharashtra to which King Shivaji of fame, belonged to.

Though the Tanjore Bhonsale clan were rank outsiders from a territorial perspective, the Kings of this Royal House went about enmeshing themselves in the social fabric of the then Tanjore area. The Kings of this House made Lord Rajagopala at Mannargudi, Lord Tyagaraja of Tiruvarur and finally Lord Brihadeesvara at Tanjore as their titular deities and for practical purposes even attempted to rule in the name of these Gods. Along with Marathi they made Telugu as well as the lingua franca of the Court, taking the previous Nayak rule as a template. The local Brahmin learned men were made the Prime Minister or Rayasam akin to how the Nayak Kings had, including the way they administered the kingdom. And lastly if not the least, the Kings though hailing from Central India, became great connoisseurs and patrons of South Indian music. The “Modi records” as they are called, which are the Royal records of this rule which has been preserved in the Sarasvathi Mahal Library in Thanjavur vouches for the retainers which has been paid to the musicians, courtesans and others attached to the Royal Court. That apart several compositions are still available to us composed on these Kings which bears testament to their munificence as well. Dr Sita ‘s ‘ Tanjore as a Seat of Music’ is a fairly complete reference for the musical history of this period.

THE HEADY DAYS OF THE RULE OF PRATAPASIMHA:

We begin the journey with King Pratapasimha whose regnal years were 1739 to 1763, one of the longest rulers in the Tanjore Maharatta Royal house. Despite many external threats he was a powerful ruler and administrator. Given his acumen, the British East India Company accorded high regard for him and he was the last King of Tanjore to be referred to as “His Majesty” in the company records from that period. All subsequent Kings became puppets in the hands of the British. Pratapasimha faced considerable odds in holding on to Tanjore given the threats from the Nawab of Carnatic and from the French. He allied with the British and in 1761, participated in the siege of Pondicherry which resulted in a crushing defeat for the French. Despite all these political upheavals, Pratapasimha played the role of benefactor and patron of arts. Many musicians and artistes flourished during his rule. Amongst so many compositions from his reign, one fine exemplar stands out, the magnum opus, the Huseini Svarajati composed by Melattur Virabadrayya, the guru and preceptor of Ramasvami Dikshitar, whom Subbarama Dikshitar alludes to in awe as ‘Margadarshi’ or “Trailblazer”. For very many decades and even well into the 20th century this Svarajathi was a piece-de-resistance with its lilting carana refrain “au rE rA sAmi vinara…….”. This masterpiece in adi tala started as “sAmi nEnarElla”, was composed on Lord Varadarajasvami of Melattur spawned many copies inspired by its melting tune and evergreen popularity. In fact Subbarama Dikshitar in his SSP has documented one such copy commencing with the words ‘ emantayAnarA’ attributing it to Patchimiriyam Adiyappayya, which bears the poshaka mudra/colophon as ‘Pratapasimha’. Pratapasimha who himself was a son of a concubine had ascended the throne by banishing the legal contender to the throne Prince Sahuji. Records indicate that when he died he had atleast two sons. The elder one and next to the throne, was Prince Tulaja II (born in 1738) through his Royal Queen. He later ascended the throne as a rightful heir. And the younger one was Prince Amarasimha, the protagonist of this blog post, a son through Pratapasimha’s concubine. Pratapasimha died on 16th Dec 1763 after reigning for 24 long years and the 25 year old Tulaja II ascended the throne.

THE TURMOIL DURING TULAJA II’s RULE

The British with an eye on assimilating the Royal Kingdom of Tanjore to its growing empire, started destabilizing King Tulaja II’s rule right from day one. Tulaja II by nature was not a formidable character like his great father and he became amenable to the intrigues, both inside and outside of the Fort at Tanjore. Implementing the divide-and-rule policy which they perfected as a fine art to perpetuate their imperialistic rule for more than 3 centuries, the British set Tulaja II against the Rajas of Ramanathapuram and the Nawab of Carnatic. To defray the cost of wars, Tulaja II was forced to borrow money and incur huge debts with the British East India Company at usurious interest rates. In fact it was Manali Muthukrishna Mudaliar ( the later day Patron of Ramasvami Dikshitar) who was then the Dubash of the then Governor of Madras, Pigot, who came periodically to negotiate financial matters with Tulaja II at Tanjore and to Tiruvarur. It was then when the Mudaliar came to be introduced to Ramasvami Dikshitar which would prove fortuitous for the Dikshitar clan, later on. The British finally forced Tulaja II into a Treaty with the result he was divested of his army and thus was rendered into a yet another tribute paying vassal of the British. Their plan to annex the Tanjore territory was complete. See Footnote 2.

Turning to matters musical, probably some time, circa 1768 is when Ramaswami Dikshitar was perhaps directed by Tulaja II to go to Tiruvarur to formulate the musical paddhathi for the Tyagaraja temple. Subbarama Dikshitar is his Vaggeyakara Caritamu, alludes to this with a dream that Ramasvami Dikshitar had, in which Lord Tyagaraja bade him to come over to Tiruvarur to carry out the divine task. We can see later that it was sometime circa 1770 that Prince Amarasimha came visiting Tiruvarur. Between the years 1780 & 1786, Hyder Ali and his son Tipu Sultan plundered the Tanjore region, driving out Tulaja II into exile. According to the records of the Christian Missionary Schwartz, children numbering more than 20,000 were carried away and the entire region was ransacked. The scorch-the-earth policy of Tipu Sultan between 1780 and 1786, the impoverished Treasury of the Tanjore King together with successive famines in the Cauvery delta due to poor monsoons during the period of 1780-1800 took a toll. Records show that the region lost the 2 decades and it recovered only after 1800, following the political stability afforded by the ascension of Serfoji II in 1799. Many people including the likes of Ramasvami Dikshitar & his family fled to Madras to be under the protective cover of the British. They were absorbed into the society by the cognoscenti of the City ( Chennapattana/Madras) namely Manali Muthukrishna/ Cinnaya Mudaliar & others. ‘Sarva Deva Vilasa’ the Sanskrit work narrates the state of the City and also the high and mighty who served the British during the last decade of 1700’s and the early years of 1800’s. Reverend Schwarz ( 1726-1798) the renowned Danish Christian Missionary was a close confidant of Tulaja II for very many years and was a faithful interlocutor for the King when he dealt with the local British Resident and the Commandant of the Tanjore Garrison. In fact given the proximity between the two, it was rumored, as accounts show, that Tulaja II had either converted to Christianity or was a closet Christian. In fact when Tulaja II adopted Serfoji II (born 1777, a son of Tulaja II’s cousin) as his son sometime 1787 or thereabouts, the British retrieved Tanjore and reinstated him on the throne, Rev Schwarz was a source of great solace and his memoirs offer a glimpse as to how Tulaja II was grieving inwardly. So much was Tulaja’s faith in this Padre that on his deathbed in the year 1787, wanted Rev Schwarz to be the guardian of the minor Serfoji. It was apparent that the dying King feared for the life of the young adopted Prince Serfoji. But the Missionary refused. We would see that he would later go on to become a philosopher and guide to the young Serfoji and support his claim to Kingship through his minority till 1799.

THE ASCENDANCE OF AMARASIMHA

Tulaja II passed away in 1787, a year or two after he had taken back Tanjore. On his deathbed he summoned the British resident and the Commandant of the Tanjore garrison and held over the minor Serfoji to their care. This was when intense jockeying started as to who would be the Regent and rule the Tanjore Kingdom till Serfoji attained majority. Prince Amarasimha the paternal uncle of Serfoji played his cards well notwithstanding the support of Rev Schwarz who was the interlocutor for the Minor Serfoji. It was quite a departure from established mores for a religious missionary to be interfering in the political affairs of the country where he had come to preach. The existing Hindu establishment in Tanjore had animosity towards Rev. Schwarz whom they considered as a meddler who was instrumental in Tulaja II’s religious bias towards Christianity which they had greatly resented. Moreover given Schwarz’s influence over the young Prince, the palace establishment was of the firm view that he too could be a potential Christian convert which would be anathema to them. Arguably this greatly tilted the balance of power in favor of Prince Amarasimha who with the connivance of the local British resident and his masters in the Madras establishment, successfully wrested the Regency for himself in 1787. The problem was also arbitrated upon by religious experts from Kashi to provide inputs on Sastraic sanction for rule by Regency, royal succession etc, which in turn gave rise to allegations of bribery and chicanery. See foot note 4. It would not be out of place to mention that there were bickering going on even within the British establishment of Madras with the East India Company’s London Directors taking a very dim view of many a political happenings in India and the financial malfeasance of the Company’s Officers in India. They believed that the Company officials in India including the Governor of Madras were accumulating wealth by taking bribes from the local Princes in return for Kingship and reduction in the peshcush/tribute payable to the Company. Firmly ensconced as the Regent, King Amarasimha began his 12 year rule from Tanjore. Accounts have it that he ill-treated the minor Serfoji greatly and Rev Schwarz together with Serfoji paid several visits to Madras to plead with the British establishment there for succor. It was not to happen so easily. Matters only turned for the worse for Serfoji on his return to Tanjore as it made his uncle King Amarasimha even more inimical to his interest. (see foot note 2). Even though the rivalry and discord was simmering inside, Amarasimha could not wish away the fact that he was a Regent and so he had to necessarily present himself in public along with the boy King Serfoji. In fact many paintings from that era depict both of them in the Royal regalia, for an example see here. One account has it that in 1793, Amarasimha went ahead and proclaimed himself the King and absolute ruler, much to the chagrin of the British and the faction of the family supporting Prince Serfoji which included Tulaja II ‘s Queens. While from a political standpoint Amarasimha appears in a different light, from an arts perspective he played his role to the hilt. With an efficient Prime Minister Sivarayamantri on hand, he patronized a great number of scholars and musicians. The composer of the famous Anandabhairavi kriti, ‘Nee mati Callaga’ and that of Parijataapaharana’, Kavi Matrubhutayya was one such recipient. Apart from the Anandabhairavi kriti, we also have a couple of more available from this composer, one such being ‘tarali boyyE” in Todi, which is found notated in the SSP. (Refer pages 160-169 of Dr Sita’s work – Reference # 5 below).

THE ANOINTMENT OF SERFOJI in 1799 & THE BANISHMENT OF AMARASIMHA

Circa 1797 – Portrait of Amarsingh/Amarasimha of Tanjore Wearing a feathered turban lined with pearls and gold lace, a white chemise trimmed with fur, pearls and jewels, with a red and yellow sash, a dagger within the sash, the Brihadishwara Temple beyond, gilt-metal mount, ebonized frame inscribed on the verso of the frame: Miniature of the Rajah of Tanjore in / the East Indies given by him to Major Wiliam Monson then Commandant at Tanjore 1797; Watercolour on ivory: 9.6 by 8 cm.; 3 3/4 by 3 in.

Due to the continued efforts of Reverend. Schwarz and the change in perception of the British, fortuitously for Serfoji, moves were afoot to restore him to the throne with the taking over of Lord Wellesley as the the Governor General of India. The fact that Amarasimha’s rule wasn’t auguring well for the British became obvious and a deal was struck by the then Resident Benjamin Torin at Tanjore acting on the instructions from Governor General Lord Wellesley. ( See Foot note 3). As a part of the tripartite deal the British negotiated, Amarasimha was to move to Tiruvaidaimarudur (also known as Madhyarjunam), a few miles from Kumbakonam, where he set up his Samasthanam/Royal Estate funded by the Treasury at Tanjore. Serfoji for his part would ascend the throne giving away all the powers to the British and relegating himself as a nominal ruler from the Fort at Tanjore converting the Kingdom in essence to a Principality, in return for the Privy Purse. The British plan to annex Tanjore to the Empire was complete. Some accounts have it that Amarasimha grew ill even during the Regency and in the run up to this tripartite deal. Records from a British standpoint go cold after 1799 in so far Amarasimha goes. The details if any about him reduces to a trickle thereafter. Few of such sources includes Dr U Ve Svaminatha Iyer. He is recorded as “Madhyarjunam Amarasimha” and apparently according to Dr. U Ve Svaminatha Iyer, he was the patron of Ghanam Krishna Iyer, Hindustani musician Ramdas & others. In fact the above referred Ramadas taught music to Gopalakrishna Bharathi (1811-1881) who used to reside in Mayavaram. A reconciliation of the dates of these personages and the life time of Amarasimha reveal even more confusion. It could be that Dr U Ve Svaminatha Iyer is confusing himself with Madhyarjunam Pratapasimha, the son of Amarasimha who was the successor to his father. Dr Sita in her treatise ( Reference 5, pages 104-106) provides a historical summary of the King. Given the chronology of events and logical reasoning, Amarasimha should have died sometime during the early years of the first decade of the 19th century, 1805 or thereabouts. (See Footnote 5 below)

AMARASIMHA’s DESCENDANTS:

Amarsimha’s son Madhyarjunam Pratapasimha (named after his illustrious grandfather) is briefly profiled by Subbarama Dikshitar in his Vaggeyakkara Caritamu which gives us some clue as to the timelines. He says that Madhyarjunam Pratapasimha was well versed in music and mrudangam playing. He was also a composer having created a Navaratnamalika and a ragatalamalika in mahratti language with beautiful svara patterns. According to Subbarama Dikshitar he died sometime before the period of Sivaji Maharaja. Now King Serfoji died in 1833 and Sivaji ascended the Tanjore throne that year. Thus it is quite possible that Madhyarjunam Pratapasimha died circa 1832. Barring the dilapidated palace & buildings at Tiruvidaimarudur, ( see note 6 )there exist no other artifact attributable to this branch of the Royal House of Bhonsales. We do have a couple of paintings of Amarasimha and one of Madhyarjunam Pratapasimha his son.

COMPOSITION & DISCOGRAPHY

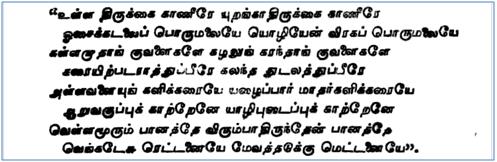

Ramasvami Dikshitar is said to have moved to Tiruvarur after his stay in Tanjore where he was patronized by King Tulaja II. About 1768 or 1770, he visited Tiruvarur, according to Subbarama Dikshitar, to take part in the Temple festivities. It was during this time by Royal decree from Tulaja II and/or by divine orders in his dream that Ramasvami Dikshitar embarked on codifying the musical rituals for the Tyagaraja Temple. During the temple festivities, Prince Amarasimha (as he was then, during the reign of Tulaja II) happened to visit Tiruvarur. Ramasvami Dikshitar must have been granted an audience with the Royal. And in a trice he perhaps composed & rendered a ragamalika piece ‘sAmajagamana’, which is the musical core of this blog post. The objective as pointed out earlier is to first deconstruct and quickly understand the history, the situation and the setting in which the composition was born and then deep dive into the composition, to make the experience wholesome. Now moving over to the very composition, one can see from the musical history that the entire Dikshitar clan reveled in composing Ragamalikas. The SSP has captured them for posterity in notation from which one can recreate therefrom. This ragamalika of Ramasvami Dikshitar notated in the Anubandha to the SSP,is an archetype and has the following features:

- ‘sAmajagamana’ has a Pallavi (2 ragas), anupallavi( 2 ragas) and 4 caranas( 4 ragas each). In sum we have 20 ragas which have been utilized in this composition.

- The composition is set in Adi tAla

- The Pallavi is made of 2 ragas – sAma and Lalitha which has a makuta svara section in sAma for ½ tala avarta which is rendered after the anupallavi and caranas to loop back to the Pallavi refrain.

- The anupallavi consist of 2 ragas – Hamvira ( or Hamirkalyani) and Bhupalam and muktayi svara in Bhupalam for ½ avarta of tala

- The carana section ragas are:

- 1st carana – Natta, Padi, Mohanam, Sahana, followed by muktayi svara/jathi in Sahana for ½ avarta tala

- 2nd carana- Manirangu, Kapi ( Karnataka), Shri and Durbar followed by muktayi svara/jathi in Durbar for ½ avarta tala

- 3rd carana – Kannada, Ramkali, Kalyani and Saranga followed by muktayi svara in Saranga for ½ avarta tala

- 4th Carana – Ghanta, saurashtra, Varali and Ahiri followed by muktayi svara in Ahiri for ½ avarta tala

- The raga names are expressly made part of the sahitya, segueing with it seamlessly. Ahiri appears as “A harI”, Sahana appears as ” sogsusAnanI, Hamirkalyani appears as ‘hamvIrU’, rAmakali appears right at the conjunction of the Kannada and Ramkali section and so on.

- The poshaka mudra is found in the anupallavi sahitya which goes as “Sri mahA hamvirU pratApa simhEndrUni tanaya ; chiranjeevI amarasimha bhUpAla” extolling Prince Amarasimha as the son of that great warrior King Pratapasimha. Reference is made again in the Saranga raga section as ‘ mA cakkani amarasimhEndra sAranga’.

- The entire sahitya is structured as an erotic composition with the nAyika pining for Prince Amarasimha.

A couple of important points stand out from a musical perspective:

- Usage of ragas sharing common murcchanas, being placed next to each other is a marked feature. Ramasvami Dikshitar himself in his 108 raga tala malika, ‘nAtakadi vidyAlaya’ uses the same stratagem. Even as one sings for that ½ or 1 avarta, the raga structure is made out distinctively in the midst of other ragas from the same family. In this case Manirangu, Kapi, Shri and Durbar bring that feature.

- Ragas like Hamir, Ramkali etc have traditionally been believed to have been imported into our music, by Muthusvami Dikshitar post his visit to Kashi. In this ragamalika, assignable to a date much earlier to the birth of Muthusvami Dikshitar (1775), we see the ragas Ramkali and Hamir being used, pointing to the fact that the usage of these ragas predate the Trinity.

- With the greatest of gratitude to Subbarama Dikshitar for gifting us with the SSP, one can see that he has notated Ramkali in this composition with both the madhyamas ( m and m#). In the SSP main raga lakshana text, Subbarama Dikshitar assigns Ramkali under Mela 15. And therein he mentions that it is the convention to render the madhyama of the raga as m# and gives a few sample murcchanas. But in the notation for the solitary exemplar composition(kriti) for the raga, ‘rAma rAma kalikalusha virAma”, he does not notate the prati madhyama (m#) at all. Whereas for this composition ‘sAmajagama’ in the anubandha he marks the place where the prati madhyama has to be rendered and thus provides a formal authority for the sanctioned usage. In fact the prati madhyama is so positioned by Ramasvami Dikshitar in this composition that the sahitya line in Kannada ends in M1 ( the preceding sahitya line) and the Ramkali portion begins with M2, producing the Lalitanga like effect via GM1M2G . In North Indian music this classic musical motif is called ‘lalitAnga” with the improvisation that the M2 is sandwiched between two M1’s. Additionally Ramasvami Dikshitar skillfully spreads the rAmkali raga mudra over the Kannada portion and rAmkali portion as well showing that perhaps the GM1M2G is a motif for Ramkali!

- The final carana ends with the benedictory appeal for the benign Grace of Lord Tyagaraja – “A harIndrUnI pUjincU tyAgEsa krupa nijamU”

- Just as a passing observation, we do not see the standard colophon that Ramasvami Dikshitar usually uses namely “venkatakrishna” in this composition.

This ragamalika composition as far as one knows, has never been part of the concert platform repertoire and there exists no known recording of this composition. During the music festival season of 2015, Parivadhini presented a thematic concert on Pre-Trinity compositions @ Nada Inbam by Vidushi Smt. Gayathri Girish. (See Note 7), wherein this piece was rendered. Here is the complete composition rendered by her from that concert. Accompanying her, on the violin is Dr Hemalatha and on the mrudangam by Sri. B Sivaraman.

CONCLUSION:

The virtuosity and proficiency of the great composers needs to be researched further in the context of both musical and social history. Such an effort should encompass identifying & publishing hitherto undiscovered compositions and archiving the music material to be preserved for posterity. Performing musicians too should take the lead in adding these rare and unheard compositions in their repertoire and presenting them frequently in concerts.

REFERENCES:

- Subbarama Dikshitar(1904) -Sangeeta Sampradaya Pradarshini with its Tamil translation published by the Madras Music Academy

- William Hickey (1875) -The Tanjore Mahratta Principality in Southern India- Second Edition- Published by Foster & Co. eBook published by Google

- K R Subramanian(1928 & 1988) – The Maratha Rajas of Tanjore – Published by Asian Educational Services

- Dr U.Ve.Svaminatha Iyer (2005) – Urainadai Noolgal – Part 1( Reprint)

- Dr Sita (2001)- Tanjore as a Seat of Music

FOOTNOTES :

- Tanjore was actually called the ‘Eden of the South’ as it was lush & green, a picture of prosperity coupled with the fact like just like Silicon Valley in modern U.S.A, the place became a beehive for all of performing arts. The water of the Cauvery, the fertility of the delta alluvial soil, the inclination of the people to arts, temple, religion and culture ensured that the cognoscenti flocked to the Tanjore Kings who ruled the area. In her treatise, “Tanjore as a seat of Music”, Dr Sita says that at some point the Tanjore Court hosted more than a 1000 vidvans !

- Much of the intrigues surrounding the Royal House of Tanjore during the period of 1760-1775 can be found documented in the “Original Papers Relative to the Restoration of the King of Tanjore and the Arrest of the Rt. Honble George Pigot” available here.

- This Royal skulduggery and the untold misery of Prince Serfoji was much later a subject of a historical novel “Old Tanjore” written by Seshachalam Gopalan & published by P R Rama Iyer and Sons, Madras (1938). This novel has as its plot, the intrigues at the Tanjore Court. The aspirations of Prince Serfoji, Maharaja Tulaja’s lawfully adopted son is checkmated by Amarasimha who aspires for the throne and for achieving that he even deigns to liquidate him. But the Dowager Maharani (Tulaja’s mother) and two of Tulaja’s wives who didn’t commit Sati, namely Queen Sujanabayee and Queen Girjabayee save Serfojee with the help of the famous Danish Christian missionary Schwarz. Assisting them is Tukaram Rao, a courtier and friend of Tulaja . They finally succeed in removing the Amarasimha from the throne and anointing Serfoji as King. “Old Tanjore” is a historical novel dealing with a period in Tanjore history which is at once the twilight of the Mahratta royal rule and the dawn of the British Raj. We get in it preserved with great skill, the aroma of days by-gone. And the characters and events assume a living dimension. Rev Schwarz and Tukaram, the energetic courtier who though on the same side to promote the interest of Prince Serfoji, frequently come into conflict in these pages and they realize at the last for a fleeting moment the kindred nature of their mission on earth. All these are vividly portrayed by the author Sri. Gopalan and it lends its own peculiar charm to the story. The underlying religious ferment in the ancient city which throws up a lofty character like Tukaram, the intrigues of Amarasimha to usurp the throne from the young Serfojee & persecute him, his final rescue by Schwarz & others thus constitutes the central theme of the story. One does not know whether these characters and their actions as depicted in the novel are completely true or fiction, save for a few. Wish one does. The author, Seshachalam Gopalan a resident of Tanjore much like Madhaviah another English writer from the early 20th century,seems to have written a bunch of novellas apart from ‘Old Tanjore’. These include ‘Jackal Farm or Jungle of good Jackals’ (1949) a satire, “Tryst with Destiny” (1981), “From my Kodak” and ‘Distant Views”.

- The Memoirs of Lord Wellesley, archived here by Google offers the view of the British establishment then with respect to the question of making Prince Serfoji the King. For more on Reverand Scwarz and his take on the entire affair one can refer to Lives of Missionaries in Southern India archived here by Google books. Many other documents too have been referred to and this listing is not complete.

- In those days with life span hardly exceeding 50 years on an average it is quite possible that Amarasimha’s life time was 1755-1805. It agrees well with Pratapasimha’s reign of 1739-1763 and Tulaja’s life time of 1740-1787. In the same breath given King Serfoji’s life time was 1777 to 1833 or an age of 56 years, Madhyarjunam Pratapasimha (who is a cousin) could have lived between the period of 1780-1832, assuming Subbarama Dikshitar is correct in stating the date of demise.

However another contrarian evidence emerges from the precincts of the sprawling temple of Lord Mahalingasvami in Tiruvidaimarudur where one can see in the outer prahara, a statuette of a lady with a lamp called ‘pAvai vilakku’. The temple authorities have written a commentary – see photograph, roughly translating the note written on the base of the statuette, as under:

“The Maharatta Raja Amar Singh (Amarasimha) used to reside in the palace on North Street. His son was Pratap Singh (Pratapasimha). Yamunabhayee Sahib and Sagavarbayee Sahib were respectively his first and second wives. Neither of them had any progeny. Pratap Singh desired to marry Ammanubayee Saheb, a daughter of his maternal uncle. They were deeply in love with each other. The said Ammanubayee prayed to Lord Mahalingasvami and undertook to light a 1000 lamps if her heart’s desire was fulfilled. And when the marriage indeed took place the Rani lit those 1000 lamps and she had this figurine of herself forged and installed in the temple. This is dated to Salivahana era 1775, 22nd day of the month of Jaiyshta(AnI),a sOmavAra, corresponding to 4th July 1853 of the English calendar”

This certainly complicates matters as the date of demise given by Subbarama Dikshitar doesn’t tally with the date inscribed in the figurine which should be accorded higher evidentiary value. If we are to take this into consideration, Madhyarjunam Pratapasimha must have lived well into the second half of the 19th century. On the left is the photo of the narration in Tamil found in the temple precincts, mentioned above.

6. V Sriram( 3rd Jan 2014, The Hindu) has his account of the abode of Amarasimha at Tiruvidaimarudur here. His brief narration of the historical background is entirely based on Dr Sita’s ‘Tanjore as a Seat of Music’, reference # 5 above.

7. In that concert, ‘sAmajagamana’ was presented as an exemplar for the ragamalika archetype composition and this blog author had a hand in that choice. The permission granted by Smt Gayathri Girish to share a recording of his composition in the public domain is gratefully acknowledged.

Safe Harbor Statement: The clipping and media material used in this blog post have been exclusively utilized for educational / understanding /research purpose and cannot be commercially exploited or dealt with. The intellectual property rights of the performers and copyright owners are fully acknowledged and recognized.