[simple-author-box]

Introduction:

Ghanta or Ghantarava as it has been known all through musical history has been a raga with a recorded history of more than 500 years. Though the notes forming the raga has apparently undergone change, the form of the raga today can be gauged completely only from the authoritative commentary of the raga provided by Subbarama Dikshitar in the Sangita Sampradaya Pradarshini and the two examplar kritis of Muthusvami Dikshitar therein. Curiously we do have a couple of compositions of Svati Tirunal too which depict the raga as found in the kritis of Dikshitar. The raga being purva prasiddha and takes multiple types of the some notes, it defies a categorization under any raganga/mela and its alignment under Todi (mela 9) or under Natabhairavi (mela 20) is a mere formality as these rAgAngAs do not contribute to Ghanta’s melodic individuality in any way.

Simply put, Ghanta is usually labeled as a misra raga – a raga which is an admixture of two or more ragas. In fact practitioners usually opine that the hues of a number of ragas including Dhanyasi, Bhairavi, Todi, Asaveri and Punnagavarali show up in this raga.

However the commentary provided by Subbarama Dikshitar and the two compositions of Dikshitar provides us with an ample view of this raga which is hardly ever performed on the concert stage today. Its musical definition also gives us a perception that it is a ‘designer’ raga – in other words it is a raga which can be interpreted or presented in different hues and colors and thus provides the performer or the composer as the case may be the leeway to present it as they imagine.

Ghanta is sought to presented in this blog post as a musical offering to the Mother Goddess on the auspicious occasion of Navaratri. Two prime exemplars presented in this post have been composed on the Devis from two kshetras namely Goddess Kamalamba of Tiruvarur and Goddess Mangalambika at Kumbakonam.

Over to the raga and the compositions!

The History:

Starting from Svaramelakalanidhi of Ramamatya ( circa 1550 ) to the Sangita Sampradaya Pradarshini (1904) Ghanta has been part of the southern musicological literature. Barring Somanatha (circa 1609) almost all Southern musicological texts talk of Ghanta or Ghantarava. The parent mEla/ragAngA and therefore the notes seem to have changed over a period of time, oscillating between Kannadagaula or Sriraga or Bhairavi mela. Meaning the rishabha or the dhaivatha svara or both has been changing. The gandhara, madhyama and nishadha svaras have been unchanged and have been only sadharana (G2), suddha( M1) and kaishiki (N2) respectively.

To assess the musical worth & history of a raga in currency today, one needs to look at the compositions of the Trinity and the musicological literature which were authored in the run up to the times of the Trinity & it is the triad of:

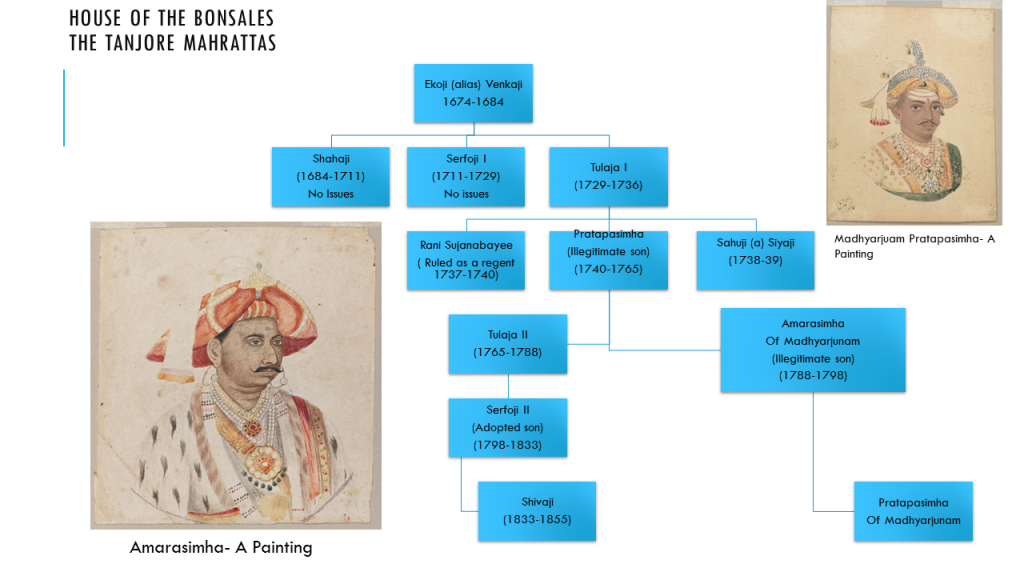

- The Ragalakshanamu of King Sahaji (circa 1700)

- The Sangita Saramruta of King Tulaja (circa 1730)

- The Ragalakshanam or the raga compendium of Muddu Venkatamakhin (circa 1750)/Anubandha to the Caturdandi Prakashika which is documented by Subbarama Dikshitar in his Sangita Sampradaya Pradarshini (SSP hereafter)

In the context of Ghanta as a melody, with reference to the above three musicological texts the following is the summary for our understanding:

- All the three texts in unison place the raga under Bhairavi/Narireetigaula – modern mela 20. The original Caturdandi Prakashika (circa 1620) also places Ghanta under Bhairavi.

- The note dhaivata (suddha) or D1 is prescribed as the graha, amsa and nyasa according to Tulaja and Muddu Venkatamakhin. Even in Chaturdandi prakashika, Venkatamakhin marks dhaivatha as the graha, amsa and nyasa svara.

- Ghanta is described as both a ghana and naya raga by Shahaji

- While according to Venkatamakhin and Tulaja, the raga can be sung at all times, Muddu Venkatamakhin deviates and prescribes that the raga is to be rendered in the evenings.

- Sahaji has not only documented the raga in his work but has also used it in his Pallaki Seva Prabandha. This opera was resurrected by the Late Prof Sambamoorthi who notated & published it after hearing it being rendered by an aged performer in Tiruvarur. Bottom-line is that this melody had been extremely popular and had been used well by composers in the 1700’s in the run up to the Trinity.

- Barring a cauka varna, a pada and a handful of kritis, the raga has not been invested with any tAna varnAs or tillanas or such other compositional forms.

- Tulaja and Sahaji also refer to another raga named Indughantarava which has no relation to Ghanta. It is melodically equivalent to Margahindola of modern times.

- In the run up to the Trinity, Ramasvami Dikshitar, father of the Trinitarian has utilized Ghanta in his ragamalikas – for example ‘sAmajagamana’, corresponding to the same lakshana adopted by Dikshitar which has been covered in an earlier blog post.

From a musical angle the following points merit our attention:

- From the fact that the raga had been placed under the Bhairavi, it follows that the dominating notes/svaras are catusruti rishabha R2, sadharana gandhara G2, suddha madhyama M1, pancama P, suddha dhaivata D1 and kaisiki nishada N2. The usage of suddha rishabha R1 and catusruti dhaivatha D2 notes and the combinations in which they occur is pointed only by Subbarama Dikshitar in his SSP. In fact none of the older treatises including the Sangraha Cudamani as a rule, talk about the anya svara/foreign notes of the so called bhashanga ragas.

- So one has to fall back on the commentary provided by Subbarama Dikshitar for assessing the so called foreign notes in this raga. Curiously in his notation for the two compositions of Muthusvami Dikshitar and his own sancari that he gives under the raga, Subbarama Dikshitar does not mark the types of rishabha and dhaivata in the notation of the compositions.

- Only in his raga commentary does Subbarama Dikshitar elucidate the svara type to be used for rishabha and dhaivata. Also he alludes to the usages as prevalent in practice and we need to resort to that when we interpret the notations.

- The usage of the dhaivata note as graha svara is evidenced by the fact that the graha svara passage for the raga is present in the lakshya gita printed by Subbarama Dikshitar, which he attributes to Venkatamakhin, but it could have been actually composed only by Muddu Venkatamakhin. In the modern context the graha svara does not have any melodic or practical significance. In a related context there has also been a view that this raga is a dhaivatantya raga, but the notation or the raga lakshana documented in major treatises do not support this view.

- We do have some ragas in the firmament of our Southern music, which have designated times for rendering. In the Sangita Sampradaya Pradarshini we do have a small set of ragas which have time designated as a part of the lakshana shloka ( of Muddu Venkatamakhin), some of which are under:

- Gaurivelavali, Dhanyasi, Bhupala, Sailadesakshi – Early morning – ‘prAtah kAlE pragIyatE’

- Revagupti & Bhauli – last or fourth quarter of the night – ‘tUrIyayAmE gEya’ or caramE yAmE pragIyatE

- Gauri, Sri, Bhairavi, Ghanta, Madhyamavathi – evening – ‘sAyamkAlE pragIyatE’

- Ahiri – First quarter of the night – ‘bAnayAmE pragIyatE’

The time of rendering of a raga in the context of Carnatic ragas seems to have gone out of vogue completely. The type of notes constituting the raga and the time of rendering also doesn’t seem to have a plausible correlation, making this entire feature an archaic one. Irrespective of that, Ghanta has been marked for rendering in the evenings in the company of Bhairavi, with which it shares a common body of murccanas/notes.

SUBBARAMA DIKSHITAR’s COMMENTARY ON THE RAGA:

From a raga lakshana perspective according to Subbarama Dikshitar on the authority of Muddu Venkatamakhin, the murccana arohana & avarohana for Ghanta are as under:

Arohana murccana : S G R G M P D P N D N S (or) S G R G M P D P N S

Avarohana murccana :S N D P M G R S

Before we embark on dissecting the raga lakshana in the SSP, a few clarifications are in order:

- The raga is classed as a ‘upAnga’ raga under nArirItigaula ( rAgAngA 20) by Muddu Venkatamakhin and by Subbarama Dikshitar. The word upAnga/bhAshAnga had a different connotation then in 1750’s in contrast to what is prevalent today. Suffice to say that in today’s parlance, Ghanta is a bhAshanga rAga irrespective of whichever mElA we put it under as it employs both varieties of rishabha and dhaivatha. Point is one shouldn’t be confused with Subbarama Dikshitar’s grouping of this rAga as an upAngA in the SSP.

- In his commentary for Ghanta, Subbarama Dikshitar alludes to the terms pancasruti dhaivata and trisruti rishabha. In the modern context they refer respectively to catusruti dhaivatha (D2) and suddha rishabha (R1) only.

That said, a reading of Subbarama Dikshitar’s commentary in the SSP together with the notation of the two Dikshitar compositions provides us with the following inputs:

- Permitted murccanas in the arohana & avarohana krama are as under:

- SGR1S, SR1S, SGR2GMP, PD1P, ND2NS, PNS

- SND1P, MGR2S

- According to Subbarama Dikshitar, the repeated usage of the phrases SGR2GM and PND2NS makes the raga beautiful. In other words they are the leitmotifs of the raga. The compositions also make use of another leitmotif D1ND1P as well.

- The notes G, M, D and N are heavily ornamented with the kampita gamakas.

- Catusruti dhaivatha ( D2) occurs only in the phase ND2NS. All other usages are only of suddha dhaivatha (D1)

- Suddha rishabha occurs in SRS , nRS and SGRS

- Subbarama Dikshitar makes no mention of Ghanta being a misra or a chAyAlaga rAga, just as how he makes a mention as a footnote for raga Jujavanti.

While Subbarama Dikshitar has indicated these in the commentary, he has put some qualifiers on the usages of the suddha rishabha and catusruti dhaivata. Interpreting them provides us with insights as to how the raga evolved.

- Subbarama Dikshitar opines that the singing of both types of rishabhas and dhaivatas seem to have been a post Venkatamakhi development.

Implication: So what it implies for us is that the original Ghanta/Ghantarava was a very Bhairavi’sh one and it must have been like this SGR2GMPD1NS/SND1PMGR2S. It has to be pointed out that Venkatamakhi has classed Ghantarava under Bhairavi mela in his Caturdandi Prakashika.

- The gita provided in the SSP for the raga which can be attributed to Muddu Venkatamkhin is dominated with downward/avarohana phrases. The few aroha purvAnga phrases found therein use only SGRGM. There is no SRGM or SGM found anywhere.

Implication: So SRGM and SGM were not utilized in practice in Ghanta even though there is no express disqualification. For example the lakshana sloka of Muddu Venkatamakhin does not talk about rishabha being vakra in the arohana. Thus it seems to be more a convention to use only SGRGM in Ghanta. Therefore the only route to reach madhyama from sadja is through the phrase SGRGM. In olden days it was SGR2GM only & it continues. SGR1GM is not permitted as Subbarama Dikshitar says very clearly that the suddha rishabha usage is confined only to SRS and SGRS. The leitmotif of Ghanta is therefore SGR2GM.

- Suddha rishabha occurs explicitly in SGR1S, NR1S and SR1S and nowhere else. Should we strictly interpret that these murccanas alone with R1 should be used as is, as one unit? This leaves a question whether MGRS or PMGRS should use R1 or R2. Since Ghanta is classed under Narireetigaula/Bhairavi, the default rishabha is R2 and that is what should feature in PMGRS. Interpreting or extending Subbarama Dikshitar’s commentary one can argue/surmise that if SRS or SGRS or in essence if a downward move to sadja is involved it should always feature R1 and this implies that PMGRS should feature only R1. Since Subbarama Dikshitar has not expressly called out PMGRS to be used with R1 or R2, it makes it look that either of the rishabhas can be used in PMGRS. In fact Subbarama Dikshitar says that even though it has become a practice that in other prayogas depending on circumstance both rishabhas are being used, some people sing only suddha rishabha R1. So what it means is that Subbarama Dikshitar, an avowed votary of the Venkatamakhin tradition, implicitly believed that in line with the raga’s classing under Bhairavi, only R2 should dominate but he reluctantly concedes that R1 is being used. This verbiage provides the basis for the usage of MGR1S.

- Given that the types rishabha and dhaivata has not been notated in the two exemplar compositions, based on Subbarama Dikshitar’ commentary one can derive the following rule-set to define when to use R1/R2 or D1/D2

If the murrchana is an arohana phrase- that is going to end at madhyama, the rishabha note to touch would be catusruti(R2) and the murccana will only be SGR2GM. If the murrcana is tending to the madhya sadja/avarohana phrase the preceding rishabha will be suddha(R1) and the phrase will be MGR1S. And D2 is used only in ND2NS. All other phrases would involve D1 only.

- From the commentary one can construe that by using PMGR2S one can impart the Bhairavi flavor to Ghanta and with PMG1RS an overall Todi/Asaveri feel can be given to the raga.

- The compositions in the SSP do not have phrases which avoid rishabha such as SGMP. It is always vakra as SGRGM. The usage of the phrase SGMP and the SND1PMGR1S and its prolific use imparts the Dhanyasi charge/color to Ghanta. In fact there is a documented cauka varna of Svati Tirunal ‘sA paramavivAsa’ in which the caranA refrain is only SGMP.

GHANTA RAGALAKSHANA AS DISCUSSED BY THE EXPERTS COMMITTEE OF THE MUSIC ACADEMY:

The Experts Committee of the Madras Music Academy debated the lakshana of this raga in the year 1933 ( 25th Dec) wherein it was concluded that the raga took the svaras of Todi and additionally catusruti dhaivatha (D2NS) and catusruti rishabha ( R2GM). The proceedings do not provide us with any more material evidence beyond whatever we see in the SSP.

SUMMARY:

- Ghanta had dominant notes coming from Bhairavi. Most possibly as it evolved, it picked up R1 and D2 to impart itself a different color/hue, to differentiate itself from Bhairavi.

- The phrase SGR2GM and PND3NS is to be used to impart ranjakatva/beauty to the raga.

- With R1 usage becoming more pronounced R2 usage got restricted to GR2GM.

- With R2 being so restricted and D2 being used only through ND2NS, the raga acquired a Todi flavor. Added to this was perhaps the fact that in certain versions even the SGR2GM too was dropped /deprecated and SGM coming to be used, the raga acquired a definitive Dhanyasi flavor.

- It is also likely that upper/tAra sthAyi phrases were also eschewed with the compositions using more purvanga phrases with denser R1 usage & thus giving Ghanta a more Punnagavarali feel.

- Given the usage of the two types of rishabha and dhaivata and considering its antiquity like Bhairavi, Ahiri etc it would be a futile exercise to group it under a particular mela/rAgAngA.

- From an interpretation perspective, instead of individual notes Ghanta can at best be understood in terms of murcchanas/phrases which would be the building blocks. The choice phrases are SR1S, SGR1S, SGR2MGR1S, SGR2GMGR2GM, GMPMGR2GM, MGMPD1P, D1PND1P, D1ND1P, PND2NS, PNS, SND1P, ND2ND1P, PD1MPGMP, PMGR2GMGR1S etc

- Rishabha is never a graha/nyasa note – in other words it is never a starting or an ending note.

- PMGR1S and PMGR2S may both be permissible. However if we have to have a consistent way for usage of R1 it may be better to avoid PMGR2S. That way the application of the R1 note would be explainable and orderly.

- SGM or SMGM or SRGM usage is not permitted or atleast is not a permitted usage in the tradition of Venkatamakhi as evidenced by the compositions of Dikshitar

- If one were to render the two compositions of Dikshitar given in the SSP, one can use the above rules to interpret the notation without doubt and derive a clear version of the raga.

- In sum Ghanta is a designer raga with the liberty to a composer or a performer to choose amongst those melodic blocks to build a particular version/flavor of raga. In fact with this conclusion in mind one can even hypothesize that Dikshitar in fact chose to impart a unique melodic feel to this raga by emphasizing GR2GM, ND2NS etc which is pointed out by Subbarama Dikshitar as imparting beauty to the raga.

GHANTA ONE SEES IN PRACTICE:

As one can see from the above by adjusting the usage of R1/R2 and to a lesser extent D1/D2, Ghanta of a type or flavor can be created for a composition or a portion of the composition. This can be as under:

- Dominant usage of R1/D1 along with SGMP usage – Dhanyasi flavor- portions of Svati Tirunal’s cauka varna is an example

- Dominant usage of R1/D1 eschewing tara stayi phrases and having denser purvanga phrases with more Todi/Punnagavarali flavor – portions of Neyyamuna- Kshetrayya padam can be cited as an example

- Dominant use of R2 and the phrase ND2NS/SND1P to get a Bhairavi flavor including the usage of the MGR2S phrase which Subbarama Dikshitar perhaps believed was the version in the true Venkatamakhi tradition.

- Equal usage of R1 and R2 through the appropriate phrases and embellishing it with the GR2GM and ND2NS and generating the flavor of Ghanta , with MGR1S. Most of the available versions of the relatively better known Dikshitar Navavarana composition ‘Sri Kamalambike’ fall in this category. Other examples are the kritis of Svati Tirunal notated by Sangita Kalanidhi T K Govinda Rao- for instance the kriti ‘pAlaya pankajanAbha’.

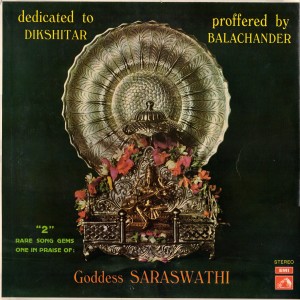

DISCOGRAPHY:

- Presented first is the Dikshitar Navavarna kriti as found in the SSP rendered to tanpura sruti by the late Vidvan Pattamadai Sundaram Iyer, from a home recording. This is an example of Category 4 above. Apart from the standard phrases, Sundaram Iyer unambiguously uses only PMGR1S only and the catusruti rishabha usage is restricted to SGR2GM & such other madhyama/pancama ending phrases.

Two curious points in his rendering merit our attention. One is the way he intones the dhaivatha occurring in the carana portion santApahara trikona gEhE. He also renders the madhyamakala carana line as “pancadasa tanmAtra visikA”. The SSP as well as Sri Sundaram Iyers’ guru Sangita Kalanidhi Kallidaikurici Vedanta Bhagavathar’s ‘Guruguhaganamruta varshini’ carry the text of this composition only as ‘pancatanmAtra visikA’. The incorporation of the words “dasa” seems inexplicable.

2. Sangita Kalanidhi T Visvanathan, who comes in the lineage of Sathanur Pancanada Iyer, a disciple of Tambiappan in the sishya parampara of Dikshitar renders this navAvarnA composition. This version is perhaps traceable to Sri T Visvanathan’s guru Sangita Kalanidhi Tiruppamburam Svaminatha Pillai. Though Sri T Visvanathan was a grandson of Veena Dhanammal and learnt a number of Dikshitar compositions from his mother, mother’s sister and off course from his sisters Sangita Kalanidhis T Balasarasvati and T Brinda, this composition and the other navAvaranA ( except the dhyAna and the mangala kritis) krithis were never part of their repertoire, since it was not taught to them. This version of the Ghanta navAvaranA must have been possibly learnt though Flute Svaminatha Pillai tracing back to Tiruppamburam Natarajasundaram & to Sathanur Pancanada Iyer who in fact was the guru of Veena Dhanammal as well.

The recording below is an excerpt from Sri T Visvanathan’s lecture demonstration in the Music Academy on 27th Dec 1986 . He is accompanied by Vidvan Sri Tyagarajan on the violin and Vidvan Sri Raja Rao on the mrudangam. And rightly so at the outset Sri Visvanathan provides his commentary on Ghanta ahead of the rendering.

Attention is invited to the kAlapramAna of his rendering, the gAyaki style in which he plays so much so that one can decipher the sahitya & its intonation and the delightful way in which he sings in the interludes which enhances the overall appeal of his presentation. As in the case of Sri Sundaram Iyer’s rendering, attention is invited to the carana sahitya “santApahara trikona gEhE” wherein the dhaivata being intoned by Sri T Visvanathan is very much closer to D1.

Overall while Sri T Vishvanathan sticks to the standard version of Ghanta in his presentation, attention is specifically invited to the madhayama kala section of the carana beginning ‘amtah karanE’. In this section, in the sahitya line ‘dyamta-rAga-pAsadvEsAm-kusadharakarE(a)tirahasya-yOginiparE’ he completely eschews R1 both in the madhya stAyI and in the tAra sthAyi segments and gives a completely Bhairavi’sh touch to Ghanta. The svara notation for that portion as he renders is “N..S G R2 R2 S N N S D1 N S R1 S N D1P M G R2 S || P D1”. In the concurrent versions, this entire segment is always rendered with R1 only and R2 is not invoked at all. It needs to be pointed out that this interpretation is well within the ambit of Ghanta and has been pointed out for we do have a reliable authority for such an interpretation. One can reasonably surmise that for ranjakatva, usage of R2 had been sanctioned as needed! Thus while for most of the kriti, the rendering falls in category 4 above, the rendering of the carana madhyamakala sahitya portion qualifies for categorization under 3 above.

- Presented next is the rendering of the very rare Dikshitar composition ‘Sri Mangalambikam”, composed by him on Goddess Mangalambika, the consort of Lord Kumbesvara at Kumbakonam. She is said to be residing on a Sri Vidya mantrapeetha. Govinda Dikshitar the grand patriarch of the Venkatamakhin school after illustriously serving the Nayak King Raghunatha , sometime circa 1600 retired to Kumbakonam to spend his last years worshipping this Devi. Even today right outside the prahAra of this Devi’s temple one can see the vigrahas/statuettes of Govinda Dikshitar and his wife Nagamamba (parents of Venkatamakhin) facing Goddess Mangalambika. A towering and beautiful idol/mUla vigraha in the sanctum sanctorum is an awe inspiring sight for the devout. The Goddess has also been eulogized by Mahavidvan Meenakshisundaram Pillai ( the preceptor of Dr U Ve Svaminatha Iyer) through his Mangalambikai Pillai Tamizh. ( See Foot note 1) The rendering is by this blog author, inspired by the notation in the Sangita Sampradaya Pradarshini and validated by a senior performing musician.

The rendering is as per the standard interpretation of Ghanta under category 4 above. The composition is extremely heavy and of the highest stylistic order. It resembles in its construction, the rarely heard Bhairavi kriti “AryAm abhayAmbAm”, in terms of both musical and lyrical worth. The composition bears the raga mudra as always along with the composer’s guruguha mudra.

There are a bunch of compositions which are available from other composers in Ghanta & the recordings of which are available in the public domain. The following are some of them which may be listened to enhance our understanding.

- The rendering of “Neyyamuna” , pada of Kshetrayya by Sangita Kalanidhi T Brinda – Labeled as Ghanta, this version does not have R2 and D2 at all.

- Tyagaraja’s mangalam in Ghanta – Renderings of this mangalam has more of Punnagavarali as its flavor.

- The rendering by Sangita Kalanidhi Mani Krishnasvami of Tyagaraja’s ‘ gAravimpa rAdA’ – The contour of the melody which is being sung is nowhere near the classic melodic identity of Ghanta. I believe it is a case of mis-labeling this composition’s raga. Tyagaraja apparently never disclosed the raga of his songs and it was finally left to his disciples and latter day editors of his compositions notably the Taccur brothers to tag the compositions with raga names they though fit. In fact Sri K V Ramachandran and a host of others with authority/evidence, in their lecture demonstrations in the Music Academy have forcefully argued that a number of the Bard’s compositions have been a victim of this mis-labelling. I strongly feel that this composition is yet another victim. The raga of this song is not Ghanta and is something different which I leave it to the discerning listener to discover.

CONCLUSION:

A raga of great antiquity which has been classified as a rakthi raga and yet hadn’t had much of airtime, languishes in the Sangita Sampradaya Pradarshini. More specifically the magnum opus ‘Sri Mangalambikam” composed on the Goddess enshrined at Kumbakonam, has never at all been encountered in the concert circuit. Given the grand edifice of the composition, once can reasobaly surmise that Muthusvami Dikshitar could not have perfunctorily composed this masterpiece. Similarly he must have given considerable thought to assign Ghanta to his navAvarana composition as well. The navAvaranAs are all composed in ragas of great antiquity, with each of which of them being crown jewels of our music system. It would be in the fitness of things that concert performers resurrect and present the raga and the two exemplar Dikshitar compositions.

REFERENCES

- Subbarama Dikshitar (1904)- Sangita Sampradaya Pradarshini Vol III– Tamil Edition published by the Madras Music Academy in 1968/2006 – pages 666-671

- Dr Hema Ramanathan(2004) – ‘Ragalakshana Sangraha’- Collection of Raga Descriptions- pages 1005-1013

- Prof R. Satyanarayana(2010) – ‘Ragalakshanam’ – Kalamoola Shastra Series- Published by Indira Gandhi National Center for the Arts, New Delhi

- Dr S. Sita (1983) – “The Ragalakshana Manuscript of Sahaji Maharaja’ – Pages 140-182- JMA Vol LIV

- Prof S. R. Janakiraman & T V Subba Rao (1993)- ‘Ragas of the Sangita Saramrutha’ – Published by the Music Academy, Chennai, pages 201-205 & 207-210

- T V Subba Rao (1934) – Journal of the Music Academy Vol V, page 111

- T S Parthasarathy (1987) – Journal of the Music Academy Vol LV11 Page 55-56

FOOTNOTE:

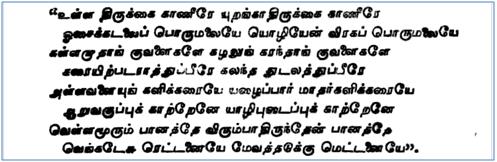

Mahavidvan Meenakshisundaram Pillai’s “Mangalambikai Pillai Tamizh” can be found in tamil script here. Amongst many of his other works, he has also composed a Pillai Tamizh on Goddess Kanthimathi the presiding deity of the temple at Tirunelveli. The legendary Sangita Kalanidhi K V Narayanasvami used to frequently render a verse as a viruttam in rAgamAlika from this work, starting with the words “vArAdhirundhAl un vadivEl vizhikku mai ezhuthEn”. Below is a clipping of one such rendering in Valaji, Varali, Nattakurinji, Begada, Saveri, Sanmukhapriya and finally Behag.

Every time I hear this rendering I get goose bumps, for I consider this veteran one of the finest in rendering ragas with the greatest rakthi and this rendering is testimony to that. One wishes if only somebody were to as soulfully like Sri K V Narayanasvami, render say the verse starting “thanE thanakku sariyAya” from the “Mangalambigai Pillai Tamizh” -Part 6 ( vArAnai paruvam), Verse 10 in a garland of rakti ragas like Begada, Sahana and Surati finally tailing into Ghanta as a prelude to “Sri Mangalambikam”. And wont it be be grand?