INTRODUCTION:

The raga Sahana is one of our crown jewels, a rakti raga par excellence. Almost every composer in our genre of music must have composed one in this raga. Surprisingly this raga is not a melody of great antiquity either in terms of it name or melodic contours. In fact when it was born or at the time it was conceptualized in our music, it was not what it is today. It had a different form and over a period of time much like how a caterpillar becomes a butterfly, Sahana underwent a metamorphosis to be what she is today.

Being a very popular and ubiquitous raga, the idea of this blog post is not to look at the basics of this raga, but to evaluate its musical history and find how it likely evolved to what it is today.

Read on!

TEXTUAL HISTORY:

Sahaji’s Ragalakshanam dateable to circa 1700 or his descendant Tulaja I’s Saramruta collated circa 1736 do not speak about Sahana or any equivalent raga sharing its same melodic structure. In Northern music the raga name is associated with the Kanada family of ragas – Shahana Kanada, Nayaki Kanada et al and thus one is tempted to consider the possibility of the raga being imported into our Southern Music system by the travelling music itinerants. We can look at the possibility of the northern variant’s similarity to our Sahana but that would form no evidence for that having influenced the formation and features of the Southern Sahana unless we have a reliable evidence. From a musicological perspective only the Ragalakshanam/Anubandha to the Caturdandi Prakashika dateable to circa 1750 and the probably subsequent Sangraha Cudamani of Govinda are the earliest musical compendia listing Sahana as a raga. Thus the Sangita Sampradaya Pradarshini ( SSP) of Subbarama Dikshitar (1905) becomes the first treatise to provide us with a ring side view of what Sahana was as it is completely based on the Anubandha text. The exemplars in the SSP and the commentary of Subbarama Dikshitar are solid evidence for us in determining the origins and svarupa of Sahana. See foot note 1.

We do have a few collateral evidences dating back to the 18th century which provides an outside-of-SSP view as to what Sahana was or is today. Let us have a look at the material available to us.

THE EVIDENCE OF THE SSP:

On the authority of the Anubandha which Subbarama DIkshitar relies on to provide the raga schemata, Sahana is placed under by him under Sriraga, which is the raganga/mela #22. Thedescription given in SSP can be summarised as under:

- It is under mela 22 and so apart from sadja and pancama it sports R2, G2, M1, D2 and N2 in its arohana/avarohana.

- Sahana is grouped as a bhashanga janya of Sriraga. But if one were to look at the raganga lakshya gita for Sriraga in the SSP, which is ‘Sridhara rE Inkita’ in matya tala, under the enumerated bhashanga ragas therein, Sahana is not be found at all. This lakshya gita though attributed to Venkatamakhin( circa 1636) himself by Subbarama Dikshitar, in all probability is a later day creation attributable to Muddu Venkatamkhin the presumed author of the Anubandha. Sahana is not of the 17th century vintage at all and never does Venkatamakhin talk about Sahana in his Caturdandi Prakashika. That said, we will leave this point as is, with the observation that this data point will be a key for us to determine Sahana’s evolution.

- As described in the lakshana sloka, in the arohana pancama is vakra appearing as MPMD.

- Muddu Venkatamakhin, the probable author of the anubandha makes as telling statement in the lakshana shloka as – ‘gIyatE lakshyavEdibhihi’ – meaning much beyond the lakshana, lakshya or practice is the key determinant or sound practical knowledge is required to understand/render the raga.

- With the practical implementation in mind, Subbarama Dikshitar provides the murrcchana arohana/avarohana karma as is his wont, duly highlighting the graha/jiva svaras of Sahana.

Arohana : S R G M P M D N S

Avarohana: N N D P M G G R G R S

- Attention is invited to emphasis given as janta for Nishadha and gandhara and the elongated rishabha note ( in bold italics) in Subbarama Dikshitar’s notes.

- In his fairly elaborate commentary Subbarama Dikshitar states that the raga is known as sAnA, sahana and shahana as well and is a desi raga.

- From a veena perspective, Subbarama Dikshitar provides instructions as to how the the dirgha nishadha, dirgha and janta gandhara has to be played.

- In so far as the gandhara goes, both in arohana and avarohana while the default type is G2 or sadharana gandhara, the G3 or antara gandhara also shows up in few places.

- GMRS is a musical motif and the gandhara alos comes with its unique kampita gamaka. Other prayogas include RGMP and PMDNS.

- He makes another telling comment that for the nishadha and gandharas, the notes must always be ornamented with the orikkai gamaka. We will elaborate on this as well in the next section.

- He concludes that given that the edict for this raga is ‘gIyatE lakshyavEdibhih’, the gandhara and nishadha svaras must be sung/intoned as how it is being done in practice or sampradaya.

- Normally for old ragas, as a standard practice one can see that Subbarama Dikshitar provides gitam and tanam as exemplars for the raga, in the SSP. For Sahana we see that apart from this lakshana shloka( from the Anubandha) , Subbarama Dikshitar provides 2 kritis of Muthusvami Dikshitar, a kriti of Ramasvami Dikshitar, a varna of his and his own sancari as exemplars.

OUR APPROACH:

Subbarama Dikshitar is the first recorded musicologist to provide a commentary on this raga and hence his views are core and invaluable for us. To understand the raga and its history/evolution we need to:

- Distil our observations from Subbarama Dikshitar’s commentary

- Evaluate the notation of the provided compositions in the SSP to understand the raga’s implementation

- Triangulate the inferences/data points with the external sources including other sources and also commentaries of modern day musicological experts.

- Hear out the compositions as rendered in practice.

- Determine the consensus theory and observed practice

- Attempt to reconcile theory and practice and finalize our understanding as to the evolution of the raga and its present or true melodic svarupa or contour

INFERENCES FROM SUBBARAMA DIKSHITAR’s COMMENTARY:

A perusal of modern musicological works and also by hearing present day version of Sahana at the outset would show that the gandhara of Sahana is definitely G3 or the sharper variety is what is profusely used and that the books provide Sahana as a janya of Harikambhoji mela. Now we do see that Subbarama Dikshitar’s commentary departs from the above. Parking that aside let us consolidate the inferences first.

- The raga is a desi raga meaning it made its way to theory, from practice. It was evolved in the public domain, enjoyed the airtime with listeners and musicians and then it became important enough to be inducted into the portals of our music as a formal raga , distinct in its svarupa, appeal and capable of being moulded into compositions.

- Based on its svara collection as it was practiced Sahana was tagged to Sriraga mela. And the collateral inference is that the dominant svara for Sahana is G2 or sadharana gandhara as that is the gandhara for the mela 22. And he does say that G3 occurs sparingly or not that profusely.

- Sahana is not to be found in the Sriraga lakshya gitam nor does it have gitams and tanams of the purvacaryas or Muddu Venkatamakhin. Also from the language Subbarama Dikshitar employs it is evident that he is looking to practice- current and past as the authority for the lakshana rather than extant older compositions- gitas and tanas which were anyways unavailable. This gives us a clue that the raga is most probably of post 1750-1770 vintage only. Had it been prior to 1750 or so, Sahana would have been formally mentioned in the Sriraga lakshya gita and also one could have seen a gita or tana of Muddu Venkatamakhin.

- Gandhara and nishadha are jiva svaras and are to be rendered with sampradaya in mind. Practical delineation trumps theory in so far as the gandhara of Sahana goes.

- The key to presenting/intoning the Sahana gandhara is that the

- Dominant variety of gandhara to be used is G2 and G3 is marginal in use.

- Orikkai gamaka type has to be used

- The GMRS though not expressly made part of the murccana avarohana, Subbarama DIkshitar in his commentary says that the GGRS which is encountered is ĜĜmRS

- One can infer that Subbarama Dikshitar has presumably only gone on to document the raga Sahana as practiced by the Dikshitar family. Apart from the Dikshitar family compositions he does not deign to provide any more as exemplars. In contradistinction to Devagandhari of mela 29, Subbarama Dikshitar does not volunteer to give kritis outside of the DIkshitar fold. Its highly likely that he must have considered other compositions but they did not conform to the Sriraga mela implementation of the Dikshitar/Venkatamakhin sampradaya or to be precise the implementation of the Dikshitar family.

- One other point to note is that apart from the lakshya gitams of the Venkatamakhin lineage- specifically that of Venkatamakhin, Muddu Venkatamakhin, presumably the ones of Venkata Vaidyanatha Dikshitar and that of Ramasvami Dikshitar, Subbarama Dikshitar does not provide those of others in the SSP. While in the Pratamabyasa Pustakamu he does provide the gitams composed by others for example Paidala Gurumurti Sastrigal. This is generic point with reference to the SSP which we will quote subsequently.

EVALUATION OF THE NOTATION OF THE EXEMPLAR COMPOSITIONS:

Let us move on to the evaluation of the exemplar compositions presented in the SSP. As pointed out earlier only those from the Dikshitar family are presented. They are:

-

-

- Vasi vasi – Adi tala – Ramasvami Dikshitar

- Sri Kamalambikayam – Triputa tala – Muthusvami Dikshitar

- IsAnAdhi sivAkAra mancE – tisra eka – Muthusvami Dikshitar

- vArijAkshi – Ata tala – tAna varna – Subbarama Dikshitar

- sancari – matya tala – Subbarama Dikshitar

-

The notation provided by Subbarama Dikshitar for all these indicates that they are aligned in full to his stated lakshana and commentary. They can be summarized as under:

- Sadharana gandhara dominates and antara gandhara as seen notated is minimal including the varnam. Barring this factor, the lakshana of the raga as we hear today and what we see in these compositions is virtually the same.

- Tellingly Muthusvami Dikshitar for his two kritis starts with rishabha as the graha svara/take off note. Ramasvami Dikshitar kriti as well as the varnam use sadja and pancama as the take-off notes.

- Subbarama Dikshitar’s varna has some unique prayogas such as those centred on the madhyama which one does not see in modern Sahana. In fact his varna is in the older form with an anubandha along with 5 carana ettugada svaras. Subbarama Dikshitar’s varnam on Lord Kartikeya is for all practical purposes an exemplar of the form of Sahana found documented in the SSP.

SUMMARY OF THE FINDINGS SO FAR:

Here they are:

- Subbarama Dikshitar with the apparent authority of the lakshana sloka of Sahana from the Anubandha , places it under the Sriraga mela # 22 with dominating sadharana gandhara and a sparingly used antara gandhara.

- Subbarama Dikshitar emphasizes the importance of intoning uniquely the gandhara and nishadha, based on sampradaya or practice.

The implementation of the Sahana as found in the SSP is unique for the above stated reasons and we will evaluate the point as we progress.

COLLATERAL EVIDENCE

If one were to search outside the realm of the SSP for determining the lakshana of Sahana prior to 1850, we end up with the lakshana gita of Paidala Gurumurti Sastri (PGS), which is found documented in the Sangitananda Ratnakaramu (1917). PGS was a disciple of Sonti Venkatasubbayya, the Dean of the Palace Musicians during the reign of King Tulaja II (1765-1788). Subbarama Dikshitar also says he was a junior contemporary of Ramasvami Dikshitar and was a resident of Madras, perhaps during the second half of his life. He most probably lived beteen 1750-1810 or thereabouts. Gurumurti Sastri was a prolific composer having to his credit a 1000 gitas. So much so that he was held in high esteem as an authority on all matters musical. Subbarama Dikshitar profiles him with awe and greatest of respect. He provides the Natta raga gitam ‘gAna kalA dhurandhara ‘ in his Prathamabhyasa Pustakamu, which we saw in the Gamakakriya post. Now Sahana’s lakshana is laid out threadbare by this illustrious musicologist PGS. Here is the text of the lakshana gita which is set in Sahana itself and in matya tala.

kamsAsurakhandana rE murArE

gopikAjAra navanItacOra yadavAbdhicandra

krupAsAndhra narakAntaka rukminIsatyabhAmAvilasita

vEnunAdapriya rE surasEvya pAhimAm ||

sAnArAgam kAmbhojijanyam

kampitagAndhAram dIrghamadhyamam

dhaivatAvakra nishAdhakampitalasitam vakrasampUrnam

gurumUrtE cidrUpArjuna sArathE bhAshAnga rAgam srunu jaya krupAlO ||

We will see the rendering of this gitam as per notation and the lakshana provided therein, shortly. But in the meanwhile when we look into the lakshana a few points strike us immediately.

- The gitam is paean to Lord Krishna and the first part of the composition bears it out.

- In the second part of the gita which is dedicated to defining the raga lakshana/grammar, at the outset PGS says that the raga is sAnA, which perhaps was the preferred or default name.

- According to PGS, Sahana is an offspring of Kambhoji, born out of it. In modern day parlance it is a derivative/janya of Harikamboji or mela 28, making the default gandhara G3 or antara gandhara.

- PGS follows up by saying that the gandhara is kampita. In other words it is a well oscillated gandharam. We need to determine if the oscillation needs to be wide enough to sometimes make it G2. Or is it likely that the gandhara is trishanku in nature, i.e somewhere between G2 and G3?

- Next he says the madhyama note is dirgha

- PGS now throws the spanner in the works saying dhaivata is vakra

- Then he says the nishada is again kampita or well oscillated.

- And lastly he says sAnA is vakra sampurnam that is it has all the 7 notes but one of them is vakra, in this case dhaivatha according to PGS.

- One shouldn’t be confused with his statement that Sahana is bhashanga. In the 18th century bhashanga meant that a raga was a ‘bhasha’ of a grama raga. It did not imply usage of a note foreign to the parent mela, which definition took root only during the second half of the 19th century.

Given that this is a lakshana gitam, below is a rendering of the gitam by Vidvan K Hariprasad ( see foot note 2 ) to help us understand the same better. See foot note 3.

Now that we have the lakshana as per Gurumurti Sastri and also by Subbarama Dikshitar let us evaluate and compare them as a table:

| Attribute | Subbarama Dikshitar | Paidala Gurumurti Sastri |

| Mela/Name | Mela 22/ Sri Raga | Mela 28 / Kambhoji |

| Gandhara | Sadharana G2 | Antara G3 |

| Gamaka for gandhara | Kampita | kampita |

| Gamaka for nishadha | Kampita | kampita |

| Vakra svara for arohana | Pancama | dhaivatha |

| Krama | Vakra sampurna | Vakra sampurna |

| Madhyama | Dirgha | dirgha |

There are two key points of discordance which needs reconciliation:

- The gandhara – should it be an oscillated G2 or an oscillated G3

- Vakra svara – Is it pancama or dhaivata?

On the second point if we run through the notation/matu of the PGS gitam to see if the svara dhaivata in vakra, we see prayogas such as RGMP, PMDNS , GMPDNDP, etc all of which are par for the course in modern Sahana. We do not see PNDNS for example which should make dhaivatha vakra. Given that we see PMDNS, it almost makes one suspect that the text is probably corrupt and that instead of pancama vakra, the scribal error made it dhaivata vakra. Other than that we see no reason for stating dhaivata as vakra.

We see that Subbarama Dikshitar and PGS agree almost on all the other points. The dIrgha madhyama is noticed specifically in the Subbarama Dikshitar varna. The other SSP exemplar compositions do not show a dhirgha madhyama at all.

Which makes us come to the first point which is a classic conundrum for any student of music, which can be stated thus:

What is the nature of the gandhara of Sahana that one sees in practice? Is it an oscillated G2 which sometimes shows up as G3 or is it an oscillated G3 which occasionally shows up as G2?

The answer to this question would provide us the parent/raganga for Sahana. If it is G2 then it becomes a janya of Sriraga and if the dominant note is G3 it comes under the Kedaragaula/Harikhamboji family. See foot note 6.

RECONCILING THEORY & PRACTICE:

To clear these questions for us it is time we requisition the expertise of the learned Professor S R Janakiraman. In his essay on the raga Sahana, this what he has to say:

- Subbarama Dikshitar in the SSP normally determines a raga as bashanga if for just a svara its svarastana shifts above or below even slightly. In the case of Sahana he says in the prayoga RiiiGRS ( the first R being dirgha and is so indicated), the gandhara speaks at mrudhu kampita levels. And is likely that since that RiiGRS occurs in profusion in Sahana, the default mela should be Sriraga, perhaps according to Subbarama Dikshitar. While Paidala Gurumurti Sastri rightly on the basis of the dominating svara being G3 in other prayogas, takes Kambhoji or mela 28 as the parent for Sahana. See foot note 4.

- The arohana/avarohana of Sahana is as under, with one svara vakra in the arohana ( pancama) and madhyama and gandhara being (nominally) vakra in the avarohana:

- S R G M P M D N S

- S N D P M G M R G R S

- Dirgha dhaivata of the arohana and dhirgha nishadha, gandhara and rishabha of the avarohana are the defining notes of this raga.

- One curious prayoga which is krama sampurna in its aroha which is encountered in compositions in this raga is ‘RGMPDNSR’ belying the grammar according to which pancama is supposed to be vakra.

- Further in the context of the raga’s lakshana Prof S R Janakiraman’s states that the notes of the raga defy conventional grammar.

- According to him despite the lack of clarity around the true nature of gandhara, whether it is G2 or G3, the gandhara note is an acknowledged amsa svara, implying that it adds beauty to the phrase to which it is added, much like how a diamond adds beauty to a woman’s face. Contrastingly for Sahana, rishabha is a key note and is the graha, nyasa and amsa svara. He says that in so far as Sahana and its gandhara is concerned, it is perhaps an exception to the rule stated by Sarngadeva that only if a svara is an amsa svara it automatically becomes jiva/nyasa as well. But in Sahana’s case the gandhara though is an amsa can never be a nyasa. Thus a phrase in Sahana can never ever be ended as PMGMG….. Gandhara will always be a beautiful buffer svara sandwiched between rishabha and madhyama. No phrase in Sahana can end with a gandhara note.

- Now the dhaivata of Sahana can also act as a graha svara as evidenced by Patnam Subramanya Iyer’s varnam ‘evvarEmi bhOdhana’ wherein one can experience hearing notes which are not at all intoned.

It still leaves us with some open questions but given the inadequacy of our musicological history one has to make assumptions as to certain facts based on present practice and get a closure on those questions.

MELA OF SAHANA- A QUESTION TO PONDER:

As we saw earlier, Subbarama Dikshitar on the authority of the Ragalakshanam/Anubandha groups Sahana under 22 mela Sriraga with the exemplar compositions of Muthusvami Dikshitar too being notated with G2/sadharana gandhara dominating and G2/antara gandhara occurring sparsely.

We also saw that Paidala Gurumurti Sastri a junior contemporary of Ramasvami Dikshitar and a disciple of Sonti Venkatasubbayya, groups it under Kambhoji mela 28 so that the raga’s gandhara is G3 or Antara gandhara. And Gurumurti Sastri is no ordinary authority. He was beholden as a sastraic authority of music of his days and addressed with the honored epithet of ‘veyi gita’ or a composer of a 1000 gitas, several of them being lakshana gitams and prabhandams. And he in his lakshana gitam for Sahana states that with Khamboji as a mela, Sahana is a janya thereunder. Prof S R Janakiraman speculates that Paidala Gurumurti Sastri was following the earlier Kanakambari Nomenclature scheme, wherein Kambhoji must have been the 28th mela and not Kedaragaula, which is the 28th mela in the later Kanakambari nomenclature scheme documented in the Ragalakshanam/Anubandha to the CDP which is illustrated in the SSP.

It may not be out of place to mention here that for Tulaja too Kambhoji was a Mela and not Kedaragaula, as he says unequivocally in his Sangita Saramruta. Given the authority of both Tulaja and of Paidala Gurumurti Sastri, one is forced to draw a conclusion that for mainstream musicians of the 18th century, Kambhoji was a mela for the svara combination of R2, G3, M1, P, D2 and N2. And Gurumurti Sastri places Sahana under it based on practice, though we do not know clearly which ‘system’ or taxonomy, the mainstream musicians were following then, if there was one. Khamboji had always sported the said notes and if Sahana was unequivocally under Khamboji, by logical deduction the gandhara can only be G3. See foot note 5.

While this is so, we see evidence come from unexpected quarters to the effect that the mela of Sahana is indeed Mela 28. And surprisingly that comes from the documented sishya parampara of Muthusvami Dikshitar himself. One of the prime Dikshitar sishya parampara personage is Sathanur Pancanada Iyer. He was a disciple of Tambiappan Pillai of Tiruvarur, for whose benefit Dikshitar composed the Atana vAra kriti, Brihaspate. Veena Dhanammal and Thiruppamburam Natarajasundaram Pillai were two of Pancanada Iyer’s disciples. Thiruppamburam Natarajasundaram Pillai (father of Flute Svaminatha Pillai) learnt around 200 kritis of Muthusvami Dikshitar from Sathanur Pancanada Iyer and he published the first set of 50 kritis complete with notation as vetted by Sathanur Pancanada Iyer himself, in the year 1936. This publication called Dikshitar Kirtanai Prakashikai (DKP) in Tamil was one of the first Tamil editions to publish Dikshitar composition in notation and in it the kriti ‘isAnAdi sivAkAra mancE’ in tisra eka is found notated. At the very top of the notation while giving the raga name of the composition the mela is given as mela 28/Kedaragaula (it is to be noted that as per Anubandha and the mela system documented in the SSP said to have been followed by Muthusvami Dikshitar, Kedaragaula is the raganga of mela 28 and Kambhoji is a janya thereunder). But one observation needs to be made here. In the DKP, the compositions are sequenced as per ascending order of the mela to which they pertains. And curiously the kriti ‘isAnAdi sivAkAra mance’ in Sahana, is not found notated serially under Mela 28, as published. Instead it appears next to Nayaki bunched along with the Sriraga janya ragas(mela 22) and one entry ahead of Kedaragaula which is the next as per the listing!

Be that as it may, we have the weight of multiple authorities to the effect that Sahana ought to belong only under Mela 28 and should have antara gandhara. With this we move to the discography section.

DISCOGRAPHY:

When we move to practice we do have two sets of renderings of Sahana, as we see in theory.

- One is a theoretical or strict implementation of the notation of the SSP which has prodigious G2 in its musical form and sparingly used G3, encountered here and there. Given that the notation in SSP is on these lines, one is tempted to call this as archaic or older Sahana, the form perhaps in which it was prior to 1800 which was utilized by Dikshitar. This is the Sahana of the SSP if one were to interpret the notation literally. We need to point out here that those vidvans who had learnt it from Ambi Dikshitar or from Vidvans through him, render Dikshitar’s compositions only in the modern form and not the form with dominating G2. Examples include the versions of Sangita Kalanidhi D K Jayaraman or that of Sangita Kala Acharya Kalpakam Svaminathan. Given that there is no oral tradition for this flavour of Sahana, all renderings of this type are ‘interpreted’ ones from the SSP.

- The second is the standard or the normal form with G3 to the hilt. As we will see in some of these versions the gandhara figuring in G2 in phrases such as SRGRS, particularly in the tAra stAyI falls completely to the sadharana value.

We shall see both these versions in the discography section.

SAHANA OF THE SSP WITH THE DOMINATING SADHARANA GANDHARA (UNDER MELA 22):

This ‘interpreted’ version is a rarity today and is not at all encountered in concerts. It has never been part of the orally transmitted version. In the recent past, this form of Sahana with dominating G2 and less of G3 has been encountered very rarely and we will present two of them.

First is the rendering of Muthusvami Dikshitar’s ‘isAnAdhi sivAkAra mancE’ found in the SSP. Presented is the rendering of Vidvan T M Krishna which was broadcast over AIR. In connection with this it needs to be mentioned that in collaboration with Vidvan R K Sriram Kumar, Vidushi Dr. R S Jayalakshmi and Dr N Ramanathan, Vidvan Krishna has been involved in a project to resurrect the ragas of SSP, interpreting the notation therein literally & document the same.

Here in this rendering he first prefaces the rendering with his comments on the nature of the Sahana he is about to present. He follows up with an alapana of the raga , which is singularly instructive for a student of music. The kriti rendering follows along with an equally illustrative svara kalpana.

Attention is invited especially to the RGRS and RGMP where the gandhara is G2 in nature and a sparing G3 appears here and there giving a very different appeal/flavour to the raga. In modern parlance Sahana of the Sriraga mela is bhashanga because it sports the two varities of gandhara.

Presented next is the rendering of the Subbarama Dikshitar tana varnam ‘vArijAkshi’ – an excerpt by Vidusi Sumitra Vasudev. The same is from an exclusive concert of Subbarama Dikshitar compositions done in the year 2014.

While the above two are pure interpretations of the notation in the SSP, we take up next the curious case of the so called trishanku gandhara, which we alluded to before, through the rendering of Sangita Kalanidhi B Rajam Iyer. Here he renders the Dikshitar navAvarana kriti ‘srI kamalAbikAyAM’. Attention is invited to the opening pallavi line itself where the Vidvan intones the gandhara as G2. The same may be compared with standard versions of the navAvarana kriti and the difference becomes obvious.

It is not known if Sri Rajam Iyer learnt it so from Justice T L Venkatarama Iyer (TLV). Because the others who learnt from Justice T L V or through him sing the composition is the modern form. It may not be out of place to point out that Sri Rajam Iyer along with Dr S Ramanathan, under the supervision of Sangita Kalanidhis T L Venkatarama Iyer and Mudicondan Venkatarama Iyer did the Tamil translation of the SSP for the Madras Music Academy. Inspired perhaps by the finding of the true original lakshana of Sahana that he got in the process of the translation work, one wonders if Sri Rajam Iyer then attempted to modify his version and bring it closer to the theoretical Sahana of the SSP with the dominating sadharana gandhara and thus rendered it so. One would never know.

THE STANDARD SAHANA WITH DOMINATING ANTARA GANDHARA (UNDER MELA 28):

In this section we will see the exemplar compositions of the SSP, presented not in an interpreted way, but by rendering it as per modern lakshana under Mela 28, Harikambhoji with pronounced use of antara gandhara.

vAsi vAsi – Adi tAla – Ramasvami Dikshitar

The kriti to be presented is that of Ramasvami Dikshitar’s. The kriti ‘vasivasiva’ is a concise edition of Sahana composed on Lord Kalahasteesvara of the Vayu Ksetra Sri Kalahasti. One of the very few people to render is the late Sangita Kala Acharya Smt Suguna Purushottaman. She once rendered it in the Music Academy and a rendering is available as a commercial release. Given below is an excerpt of that rendering. See foot note 7. As noted earlier all compositions in the SSP are notated with G2 and G3 and this kriti is no exception. However the rendering by the Vidushi is the standard version of Sahana. She is accompanied by Sri H N Bhaskar on the violin, Sr Neyveli R Narayanan on the mrudangam and Udipi Sri Sridhar on the ghatam.

Sri Kamalabikayam – Triputa Tala – Muthusvami Dikshitar

We did see a rendering of this composition by Sri B Rajam Iyer earlier, wherein the Sahana’s gandhara is rendered differently by him. There are very many mainstream renderings of this composition which one can say are normalized to standard Sahana.

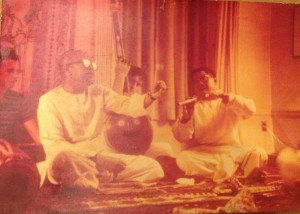

As a refreshingly different take on the composition, presented next is what one can call as a gold standard rendering. It is by Sangita Kalanidhi T Visvanathan. For me, this rendering is straight out of the Sangita Sampradaya Pradarshini, completely aligned to the letter and spirit of the notation one finds in the SSP. Barring fact that the gandhara is always interpreted as antara gandhara, Sri T Visvanathan’s rendering seems to be the best high fidelity rendering of this navAvarana piece. As the clock strikes 11 PM, the surroundings growing silent in the dead of the night, one has to listen to this rendering on a moonlit night in spring, with the faint fragrance of jasmine and other night blossoms wafting in the air. The rendering would be heavenly and the strains of the ethereal Sahana that the flute and the voice conjure up is fit for the celestials, one might say!

T. Viswanathan (flute) and T. Ranganathan (mridangam) with American students; Image Courtesy: Prof.Bruno Nettl, University of Maryland Baltimore

For students of music this is the Sahana of Muthusvami Dikshitar, to be learnt from, with the notation of the SSP in hand. The gentle giant from the past, a scion of an illustrious musical family offers us a text book lesson in Sahana with his tour de force rendering. As he himself prefaces in the comments, the Sahana of ‘Sri Kamalambikayam’ is the most contemplative one to be ever created. Hark at the beautiful pattern he weaves around ‘hrimkAra vipina harinyam’ and how he plumbs the depth of Sahana in the mandhra stAyi at ‘virinci harisAna’ and surfaces back to the madhya stayi at ‘harihaya veditha rahasya yoginyam’, like a sleek whale gracefully surfacing from beneath the ocean languorously after plumbing its depths! And Sri Visvanathan does lend his voice in the interludes tantalizing while the violinist is all subdued following him in that forest formed by the notes of Sahana. And one can notice how the tAra gandhara drops in value to almost sadharana gandhara levels at the madhyama kala sahitya beginning of the anupallavi at ‘hrIm kAra vipinaharinyAM’, (RGM RGR SnGR) For a student of music and a connoisseur alike, it is as if the ‘teacher’ within the Sangita Kalanidhi T Visvanathan, telling us that the gandhara of Sahana is not true G2 or G3. It is something in between or perhaps beyond, a gandhara unique to Sahana. Which makes it an aesthetic delight for the discerning listener of our music. Prof SRJ’s categorical statement that the gandhara note is an amsa svara without which there can be no true Sahana dawns on us as we listen to this rendering.

So much so perhaps, Subbarama Dikshitar must have struggled to categorize the gandhara and probably took shelter under a fig leaf provided by Muddu Venkatamakhin who had cryptically/pithily postulated- ‘gIyaTe lakshya vEdibhiHI’ in the lakshana shloka! And it almost makes one imagine that if Subbarama Dikshitar were around to listen to this rendering, he would approvingly nod his head without an iota of doubt and call this out as the very exemplar of what he had in mind when the purvacaryas had said ‘gIyatE lakshya vEdiBhiHI’ – this is the lakshya of Sahana!

To Dikshitar too it must have been a special choice of a raga for a navAvarana- the sarva rOga hara cakra. He had always planned to choose ragas which were old and hoary, for his magnum opus offering to the Mother. Right from Anandabhairavi, Kalyani, Sankarabharanam, Kambhoji, Bhairavi, Punnagavarali, Ghanta and Ahiri. Amongst this set of ragas, Sahana is probably the youngest in terms of musical history. As we saw earlier its inception must have only been post 1750 A D and it gathered momentum perhaps only post 1800 when it metamorphosed to what it is today. In fact by choosing Sahana, Dikshitar had anointed that it would go one to become one of the greatest rakti ragas to adorn our musical pantheon.

One is not sure from where Sri Visvanathan learnt the composition. The Navavaranas were never part of Veena Dhanammal’s heirlooms, given their content. Was it part of the repertoire that Sathanur Pancanada Iyer passed on the Tiruppamburam Natarajasundaram Pillai, the grand guru of Sri T Visvanathan (who was a disciple of Flute Svaminatha Pillai, son of Natarajasundaram Pillai)? Though Sri Natarajasundaram Pillai by his own admission had learnt more than 200 Dikshitar compositions from Pancanada Iyer, he published only 50 out of them as first and only instalment in which none of the Navavarana compositions figure. Neither do we know if the remaining compositions had the Navavaranas counted in. Be that as it may. Sri T Visvanathan’s rendering is a high fidelity reproduction of the Sahana as envisaged by the notation found in the SSP.

The other Dikshitar composition, which is attributed by some as the first kriti of the Kamalamba Navavarana kriti set- the kriti in obeisance to Mahaganapathi, Sri Mahaganapatiravatumam in Gaula which though set in Tisra triputa is usually rendered normalized to kanda capu tAla. In this context one has to be thankful that Sri Kamalambikayam which too is set in tisra triputa has not been similarly normalized and it continues to be rendered in its original tala. According to the notation it has to be rendered in 1 kalai tisra triputa tala.

isAnAdi sivAkAra mancE – tisra ekA

We move on next to the other Dikshitar kriti ‘isAnAdi sivAkAra mance’. We saw this earlier rendered with the sadharana gandhara by Vidvan T M Krishna in the first part. Presented now is the same composition in the modern Sahana, by his disciple Vidvan G Ravi Kiran.

Some years ago I was vacationing in a hill station in Southern India, staying in a British era bungalow in the midst of tea gardens. In the bungalow’s puja room I chanced upon a Tanjore style painting, which I had never seen before in that style. It was a painting of Goddess SivaKamesvari with brilliant details etched in gold and silver therein. And as I stared at it, it was getting clear. It must have been a similar form perhaps that Dikshitar must have had in mind which he musically captured in his lyrics of ‘IsAnAdi sivAkAra mancE’. Here is the snap of the picture I saw.

As one goes over the lyrics with its prAsA concordance in place, it can be seen how the vista of the picture/painting maps in toto to the lyrics of the composer nonpareil.

pallavi

ISAnAdiSivAkAramancE | SivakAmESvaravAmAnkasthE

namastE namastE gau(rISAnAdi)

anupallavi

SrISAradAsaMsEvitapArSvayugaLE | SRngArakaLE vinataSyAmaLAbhagaLE du- ||

rASApahadhurINatara-sarasijapadayugaLE | murAriguruguhAdipUjitapUrNakaLE sakaLE

(madhyama kAla sAhityam)

pASAnkuSEkshukArmuka-pancasumabANahastE |

dESakAlavasturUpa divyacakramadhyasthE||

Every sahitya line and reference has a place in this picture, if one were to watch it intently. A plainer and more frequently seen version of this photo which is also available has been given below, along with the Tanjore painting which I saw.

But the Tanjore painting of Sivakameshvari is something so original and beautiful much like this composition.

vArijAkshi – ata tAla tAna varna:

We do not have any rendering of Subbarama Dikshitar’s ata tala tana varnam in the standard Sahana. However as an exemplar I seek to present my rendering of this varnam ‘vArijAkshi nI’, interpreted to the best of my abilities from the notation found in the SSP.

A couple of observations from a practical perspective in rendering Sahana is required in the context of this varna.

- Phrases like N..GRS and R..GRS where the starting note nishadha and rishabha are dhIrgha, the following gandhara is always diminished in its svarastana, dipping to the sadharana gandhara levels. However if one were to consciously render, the phrase could sport G3 itself.

- Similar is the case of tAra sadja forays where the gandhara diminishes as aforesaid.

- Phrases like RGMP or RG.MP or PMG.R where the gandhara is dhIrgha, the gandhara gets to the full blown antara gandhara levels.

- The varna has quite a few odd prayogas including the NN.D.NDP which is the start of the carana line, where the first nishadha is plainer and the second nishadha is closer to the tAra sadja. We also see dheergha madhyama usage and also more than GMR, we the GGR where the second gandhara is tinted with the madhyama note, occurring extensively.

To simply state, if the gandhara note is to be followed by the madhayama, the tone moves to near G3 and if it is followed by rishabha the note ‘tends’ closer to G2. We did see a similar case with Narayanagaula as well in a previous blog post where the gandhara though is supposed to be G3, but diminishes to G2 in the tara sadja prayogas. It is likely that given this harmonic issue in vocal rendering Sahana was rather considered to be under Sri raga mela with G3 occurring sparingly.

OTHER COMPOSITIONS:

Tana varnas are the best repositories of raga lakshana and as pointed out earlier this varna of Subbarama Dikshitar is the sole varna exemplar of the version of Sahana documented in the SSP. While the Tiruvottiyur Tyagayyar composed ‘karunimpa’ – adi tala tana varnam is a standard staple in the concert circuit, the ata tala tana varnam, ‘evvarEmi bodhana’ of Patnam Subramanya Iyer is hardly ever encountered.

Again this composition evokes awe for our learned Prof S R Janakiraman and presented next is his commentary of Sahana followed by the rendering of the varnam . He first gives a demonstration of how Sahana has to be sung in his own inimitable way, ahead of the ata tala varna rendering.

The repository of a great tradition, Prof SRJ in this recording holds a veritable lesson for us outlining how the rishabha is a jiva svara ; how it has to be sung with so called ghana nayam ; how Smt T Brinda would bring Sahana before us at the very outset itself for ‘giripai’ with RRS and not nSRS as it is rendered today & so on. The passion and verve with which he teaches the students, is an experience in itself.

Next is a concert edition of his rendering of the ata tala varnam.

There are many other memorable renderings and also beautiful compositions including those of Tyagaraja and also of Subbaraya Sastri/Annasvami Sastri. Given the scope of this blog post we are not covering them.

A LIKELY BRIEF HISTORY OF SAHANA:

It must have been a moment in time sometime during the run up to the Trinity, probably Pratapasimha’s reign (1749-1762) at Tanjore, that this raga Sahana must have heralded its entry. Though we see no mention of this raga either in Sahaji’s or Tulaja’s works, covering the period of 1700-1736, it is very likely that there could be some Northern melody which could have potentially been a forerunner or precursor. See foot note 8.

In the bashanga raga listing under the Sriraga lakshya gita documented in the SSP, attributed to Venkatamakhin and perhaps authored by Muddu Venkatamkhin, out of the quintet, only Kapi is found. None of the others are mentioned. While these ragas are illustrated in the SSP on the authority of the lakshana sloka found in the Anubandha to the CDP, no mention is found of them in the Sri raga raganga gita in the SSP. It is likely that all of them were popular in the public domain and made it to the portals of accredited and acknowledged melodies in the raga pantheon, sometime 1750-1770 perhaps. This is obvious, as all of them are tagged as desi ragas. Dikshitar for his part composed in every one of these quintet circa 1800 or thereafter. And we even see Ramasvami Dikshitar using every one of these ragas in his ragamalikas which he must have composed between the years 1750-1800. See foot note 9.

But one factor for us to still reckon with when dating the inception of raga Sahana is fact that we have a pada of Ksetrajna ‘ moretopu’ which has been part of the repertoire of the Dhanammal family. Ksetrajna is a 17th century composer and that really sets the clock backwards for us. In the same breath we should also note that we see a pada ‘vedukato’ of his as well in the desi raga Devagandhari under mela Sankarabharanam mela 29. Devagandhari as we know again similar to Sahana is another desi raga and all other evidences point to only a 18th century induction of the raga into the musicological texts. So question is did Sahana and Devagandhari spend more than a century as a desi raga or the raga of the masses before the cognoscenti took to note of them and inducted them into the musical hall of fame by ordaining them as upanga/bashanga janyas of Sankarabharanam and Harikhambhoji sometime circa 1750? On the other hand will we be right if we were to advance the hypothesis that the said padas of Ksetrajna were tuned subsequently in Sahana or Devagandhari? One does not know for sure.

However the melismatic or rakti nature of the raga Sahana is brought to the fore by the musical contours of the famous Ksetrajna pada in this rendition by the doyenne Sangita Kalanidhi Smt.T Brinda, the quintessential musician of musicians. Here she is, showcasing one of her precious family heirlooms, demonstrating the fluid nature of rakti ragas like Sahana.

And we conclude with the memory of yet another illustrious musician of the past for whom Smt T Brinda represented all of music. And Sahana was always obligatory for him in any concert – alapana, kriti, viruttam, pallavi etc. The Vidvan is none other than the Late Ramnad Krishnan, whose virtuosity and musical acumen came to be discovered and revered much later after his premature death. This year 2016 marks the beginning of his 100th birth anniversary year and we conclude this blog post with a brilliant viruttam of his in which he encapsulates all that Sahana has to offer, in the true tradition of his illustrious mentor Smt T Brinda.

Ramnad Krishnan with T Visvanathan in Concert at Wesleyan University, United States ( Photo courtesy : Sri R K Ramanathan

Here is in this clipping which is an excerpt from a commercially available concert, Vidvan Ramnad Krishnan is accompanied by Vidvans V Tyagarajan on the violin, T Visvanathan on the flute, T Ranganathan on the mrudangam and V Nagarajan on the Kanjira and together they conjure up a Sahana, decking the up the sloka ‘jAnAti rAmam’ exquisitely for us.

CONCLUSION:

Given the controversy around the nature of the gandhara one is unable to speculate if the original Sahana indeed sported G2 predominantly. Be that as it may the raga must have surely stood out for its sheer beauty with the result Dikshitar chose it for his Navavarana composition despite being a nouveau raga of sorts.

Given the weight of textual evidence one is unable to express a view on the points whether Sahana only needs to be rendered with G2 and that the fidelity to the composer’s intent is lost otherwise. However if one were to answer this question, with aesthetics as the sole criterion, the version of Sahana with Kambhoji/Harikambhoji/Kedaragaula as parent under mela 28, resonates as the better one.

REFERENCES:

- Subbarama Dikshitar (1904)- Sangita Sampradaya Pradarshini Vol III– Tamil Edition published by the Madras Music Academy in 1968/2006

- Dr Hema Ramanathan(2004) – ‘Ragalakshana Sangraha’- Collection of Raga Descriptions – pages 1163-1164

- Prof S. R. Janakiraman & T V Subba Rao (1993)- ‘Ragas of the Sangita Saramrutha’ – Published by the Music Academy, Chennai

- Prof S R Janakiraman (2009) – Raga Lakshanangal (Tamil) – III Edition, Pages 135-137- Published by the Madras Music Academy

- Sruti (Dated June 2016) – Interview with Prof S R Janakiraman by Sri Navaneet Krishnan & Sri V Ramnarayan

FOOT NOTE 1:

The other notable musicological text which documents Sahana is the Sangraha Cudamani, which does it under mela 28 which is very clearly Harikhamboji in its scheme. Doubts exist as to date of the Sangraha Cudamani and it is most likely a second half of the 19th century vintage at the best. Hence the same is kept out of our purview in this blog post. In fact according to another text, The Mahabharata Cudamani’ Sahana is assigned to the 29th mela Sankarabharanam ! Dr Hema Ramanathan assigns a date of 18th- 19th century for this text which is a raga lexicon with lakshana slokas in Tamil. This version of Sahana sporting a kAkali nishadha is never encountered in practice.

FOOT NOTE 2:

Vidushi Savitri Rajan, a disciple of Tiger Varadacariar and Veena Dhanammal, grew intensely passionate about the musical teaching techniques and the introductory pieces that need to be taught to students of music ( abhyAsa gAnam), as documented in older texts such as Sangita Sarvarta Sara Sangrahamu and Sangitananda Ratnakaramu. Along with her students she even presented some pieces from these texts during the Experts Committee Meeting/Lec Dem Sessions in the Music Academy. An audio album of some of the pieces from these treatises too was created as a part of her initiative called ‘Sobhillu Saptasvara”. I am greatly indebted to Ludwig Pesch a student of Smt Savitri Rajan for sharing the audio of the Sahana lakshana gitam, from that initiative. Again this Vidushi and her initiative requires a separate blog post.

FOOT NOTE 3:

Apart from the other questions, the gitam of Paidala Gurumurti Sastri (PGS) and its provenance raises a couple of more questions for us:

- If for PGS, Kambhoji was the mela which system of raga categorization was he following? We know as per Anubandha to the CDP, Kedaragaula was mela/raganga 28 and Kambhoji is a janya thereunder. On the other hand the Sangraha Cudamani which is the raga lexicon supposed to have been followed by Tyagaraja, Harikhamboji was the mela 28 with Kambhoji being a janya thereunder.

- On the authority of Subbarama Dikshitar, we do know that PGS’s guru was Sonti Venkatasubbayya who he says was a follower for the Venkatamakhin system. Now if PGS were to be saying Kambhoji as a mela then does it mean that PGS was following a different system of raga categorization?

Prof S R Janakiraman in his commentary on the raga Sahana has an interesting take on the first question. According to him , if for Paidala Gurumurti Sastri, Kambhoji was a mela he must have been following the earlier or the first Kanakambari nomenclature system. And conversely by implication that for the first Kanakambari system, Kambhoji was the mela. Whereas for Subbarama Dikshitar, the later Kanakambari nomenclature system which is laid out in the Anubandha to the CDP becomes the standard. And Prof SRJ’s hypothesis probably answers the second question as well.

FOOT NOTE 4:

For example, similar to Sahana, the desi raga Devagandhari (mela 29) does not have lakshana shloka, lakshya gita and gitams. So apart from providing the composition of Dikshitar “kshitijamanam’ as exemplar, Subbarama Dikshitar also provides ‘spUratutE’ of Paidala Gurumurti Sastrigal, additionally. However in a similar such situation, in the case of Sahana, Subbarama Dikshitar does not provide any external exemplars from outside of the Dikshitar family. Neither does Subbarama Dikshitar deign to refer to Gurumurti Sastri’s lakshana gitas in his raga lakshana commentary despite the fact that Gurumurti Sastri was a disciple of Sonti Venkatasubbayya an avowed votary of the Venkatamakhin Sampradaya, even as per Subbarama Dikshitar’s own account. The Venkatamakhin Sampradaya as practiced by the Dikshitar family could perhaps have been considered by the family themselves as very unique and a class apart from the rest. Or atleast that was perhaps the impression that Subbarama Dikshitar had and that played a role in his interpreting the CDP, the anubandha, the lakshana gitas and tanams when he published them through the SSP. In the absence of collateral evidence and inadequate research of the available material, one is unable to even make an informed guess.

FOOT NOTE 5:

Assuming that the Raganga gitas were written by Muddu Venkatamakhin during the first half of the 18th century, the absence of the ragas Sahana, Nayaki and Durbar from the Dvijavanthi from the bashanga khanda of the Sri raga lakshana gitam raises several questions for us. Are the Ragalakshanam/Anubandha to the CDP and the raganga lakshya slokas which enumerate the upanga and bashanga ragas under the raganga, coeval? If the Anubandha talks of ragas not found in the raganga lakshya gitas and they themselves do not have lakshya gitas and tanas, are we to conclude that the Anubandha was a document of a much later date or it was kept updated with newer ragas whereas the raganga lakshya gitas weren’t kept updated? Now all these are valid questions in the case of Sahana. It is with this circumstantial evidence and that of Gurumurti Sastri’s gitam we are able to place a date for the raga’s inception and formal induction into the modern musicological raga pantheon.

FOOT NOTE 6:

In so far as the SSP is concerned as the context of the entire treatise us the Anubandha to the CDP, the Ragalakshanam, the reference to a raga as a bashanga is always meant to be what it was meant in 18th century. That is, a raga under a raganga will be a bashanga if it were a basha of a grama raga. That was what the meaning was for the term bashanga to all older authors, including Venkamakhin, Sahaji, Tulaja and also the presumed author of the Anubandha, namely Muddu Venkatamakhin. This definition is redundant for us today. Subbarama Dikshitar is actually confused by the term bashanga as it appears in olden texts , because during the late 19th and the early 20th century, the term bashanga had come to mean a raga which took one or more notes which were not found in its parent mela. Thus for example the Mela 20 Ritigaula raganga gitam calls the raga Gopikavasanta as a bashanga and in the raga’s commentary Subbarama Dikshitar plainly makes his confusion obvious in his commentary stating that the (his) presumed author of the gitam Venkatamakhin for some reason calls the raga bashanga, when in fact the raga Gopikavasanta has no foreign notes.

Thus in the case of Sahana, if we go by Subbarama Dikshitar’s assignment under Sri raga mela, with both G2 and G3 occurring, the Sahana of the SSP becomes a bashanga in modern parlance. However if we go with the standard Sahana that we see in practice which is tagged to the 28th mela Harikhamboji, occurrence of G2 is not reckoned at all the raga is plainly only an upanga janya under mela 28.

FOOT NOTE 7:

Apart from the kritis of Muthusvami DIkshitar found in the SSP, we do have a couple of more compositions published by Veen Sundaram Iyer in his “Dikshitar Kirtana Mala Series”, where we find compositions attributed to him but which are not found in the SSP itself. In fact during the 1950’s, even under the stewardship and watch of Dr V Raghavan and Justice T L Venkatarama Iyer, many of these compositions were edited and published by Ananthakrishna Iyer in the Music Academy Journal. Much later these compositions also made their way to the Dikshitar Kritis collection as published by Sri Rangaramanuja Iyengar and by Sangita Kalanidhi T K Govinda Rao.

It has to go on record that there always been a divergence of musical setting and lakshana between the kritis published by Sundaram Iyer and others on one hand and the SSP on the other, despite the root being the same. Normalization, editorial errors, mis-attribution and lack of fidelity are marked in very many compositions published much later after the SSP. It has to be noted with sadness that kritis of doubtful authenticity and questionable musical setting were passed off as authentic original ones and published using the musical grammar of Tyagaraja’s kritis as baseline to define the melodic contours/lakshana. In fact in hindsight it could be concluded that Subbarama Dikshitar had spent lot of effort in ‘curating’ the compositions for publication in the SSP, reconciling them with gitams/tanams/compositions and such other compositions/versions before presenting them cogently in the SSP. Suffice to say that a similar effort was never even attempted during the 1940’s-1960’s when the missed-out compositions were sought to be published. Unfortunately very many musicians who learnt those questionable pieces either from those sources or from the literal text, have propagated the same so much so that today we have no clue as to which is the authentic kriti/tune and which is the spurious one.

The only compendium of Dikshitar compositions which stands scrutiny and which has unimpeachable authority and authenticity is the Dikshitar Kirtanai Prakashikai (DKP) edited and published by Tiruppamburam Natarajasundaram Pillai in the year 1936. One can find almost complete synchronization in all aspects between this publication and the SSP, barring a couple of explainable deviations. In the case of Sahana, the DKP has notated only ‘isAnAdhi sivAkAra mancE’. Outside of the SSP one composition of merit could potentially be the Abhyamabha Vibakti series kriti, ‘aBhayAbAyAm baktim karOmI’ again is tisra triputa tala. The rendering of the same by Sangita Kala Acharya late Kalpakam Svaminathan can be listened to as an exemplar.

FOOT NOTE 8:

Sahana, Nayaki, Durbar and Dvijavanthi along with Karnataka Kapi form a quintet of ragas which probably shared a common history or evolutionary cycle. In the Northern music they were/are part of the Kanada family sharing the GMRS as a motif. As they co-evolved each of these ragas underwent changes whereby they gave up their motifs or changed them. Sahana morphed the Kanada ang as a G3M1R2S, Durbar modified it GG.RS, Nayaki gave it up or used it as G.RS and Kapi still retained it as G2M1R2S, giving it away to Kanada while it took other svaras to metamorphose into what we today call as Hindustani Kapi. This by itself warrants a separate blog post.

From the Northern regions as mentioned earlier we have so called Shahana Kanada sharing a similar name to our Sahana. Deepak Raja dwells on that raga here. The Shahana Kanada as he points out shares no resemblance at all to our Sahana. And I doubt if there is a strict melodic equivalent of our Sahana with its beautiful rishabha, gandhara and nishadha.

FOOT NOTE 9:

The quintet of ragas that we see in this blog post are seen in Ramasvami Dikshitar’s compositions – ragamalikas as under, except Dvijavanthi, as documented in the Anubandha to the SSP:

- sAmaja gamana – Sahana, Kapi, Durbar

- sivamOhana saktI – Sahana, Nayaki,

- nAtakAdi vidyalaya – Sahana, Nayaki, Durbar and Kapi

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

- Thanks are due to Vidvan Sri T M Krishna for permitting me to share his rendering of ‘IsAnAdhi sivAkAra mancE’.

- The rendering of ‘IsAnAdhi sivAkAra mancE’ by Vidvan Sri G Ravikiran was sourced from his website, where it was uploaded.

- The rendering of ‘moretopu’ by Smt T Brinda is already in the public domain and much shared. Same is the case of the recording of the Kamalamba Navavarana kriti by Sri B Rajam Iyer.

- The sloka rendering of Vidvan Sri Ramnad Krishnan and the kriti rendering by Vidusi Suguna Purushottaman are commercial records and therefore only an excerpt has been shared.

- The rendering of ‘srI kamalAmbikAyAM’ by Sri T Visvanathan was sourced from the music collection of Sri Vagheesh Narasimhan.

- The gif of the sloka ‘jAnAti rAmam’ has been sourced from the web, from the blog of Sri Sachi.

- Thanks are due to Sri R K Ramanathan for providing me with the Concert photo of Vidvan Ramnad Krishnan and Sri T Visvanathan, taken during the concert in USA which has been commercially released by Swathi Soft Solutions as a part of their Sanskruthi Series.

Safe Harbor Statement: The clipping and media material used in this blog post have been exclusively utilized for educational / understanding /research purpose and cannot be commercially exploited or dealt with. The intellectual property rights of the performers and copyright owners/creators are fully acknowledged and recognized.